Abstract

Menorrhagia affects the lives of many women. The assessment of menstrual flow is highly subjective and gauging the severity of the condition by objective assessment of menstrual blood loss is impractical. In treating menorrhagia, the primary aim should be to improve quality of life. Women are willing to undergo quite invasive treatment in order to achieve this. Drug therapy is the initial treatment of choice and the only option for those who wish to preserve their reproductive function. Despite the availability of a number of drugs, there is a general lack of an evidence-based approach, marked variation in practice and continuing uncertainty regarding the most appropriate therapy. Adverse effects and problems with compliance also undermine the success of medical treatment. This article reviews the available literature to compare the efficacy and tolerability of different medical treatments for menorrhagia.

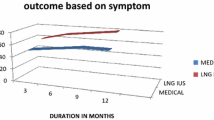

Tranexamic acid and mefenamic acid are among the most effective first-line drugs used to treat menorrhagia. Despite being used extensively in the past, oral luteal phase norethisterone is probably one of the least effective agents. Women requiring contraception have a choice of the combined oral contraceptive pill, levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) or long-acting progestogens. Danazol, gestrinone and gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues are all effective in terms of reducing menstrual blood loss but adverse effects and costs limit their long-term use. They have a role as second-line drugs for a short period of time in women awaiting surgery.

While current evidence suggests that the LNG-IUS is an effective treatment, further evaluation, including long-term follow up, is awaited. Meanwhile, the quest continues for the ideal form of medical treatment for menorrhagia — one that is effective, affordable and acceptable.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The use of tradenames is for product identification purposes only and does not imply endorsement.

References

Peto V, Coulter A, Bond A. Factors affecting general practitioners’ recruitment of patients in a prospective study. Fam Pract 1993; 10(2): 207–11

Mcpherson A, Andersson ABM, editors. Women’s problems in general practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983: 21–41

Bradlow J, Coulter A, Brooks P. Patterns of referral. Oxford: Oxford Health Services Research Unit, 1992

Shaw RW. Assessment of medical treatments of menorrhagia. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1994; 101Suppl. 11: 15–8

Hallberg L, Hogdahl AM, Nilsson L, et al. Menstrual blood loss: a population study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1966; 45: 320–51

Cole S, Billewicz W, Thomson A. Sources of variation in the menstrual blood loss. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Commonw 1971; 78: 933–9

Haynes P, Hodgeson H, Anderson A, et al. Measurement of menstrual blood loss in patients complaining of menorrhagia. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1977; 84: 763–8

Market and Research International (MORI.) Women’s health in 1990. Market Opinion and Research International, 1990. (Research study conducted on behalf of Parke-Davis Laboratories)

Cameron IT. Menstrual disorders. In: Edmonds DK, editor. Dewhursts textbook of obstetrics and gynaecology. 6th ed. Boston: Blackwell Science, 1999: 410–419

Coulter A, Peto V, Jenkinson C. Quality of life and patient satisfaction following treatment of menorrhagia. Fam Pract 1994; 11: 394–401

Coulter A, Bradlow J, Agass M, et al. Outcome of referrals to gynaecology outpatients clinics for menstrual problems: an audit of general practice records. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1991; 98: 789–96

Gath D, Cooper P, Day A. Hysterectomy and psychiatric disorder: 1. Levels of psychiatric morbidity before and after hysterectomy. Br J Psychiatry 1982; 140: 335–40

Clarke A, Black N, Rowe P, et al. Indications for and outcome of total abdominal hysterectomy for benign disease; a prospective cohort study. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1995; 102: 611–20

Cooper KG, Jack SA, Parkin DE, et al. Five-year follow up of women randomised to medical management or transcervical resection of endometrium for heavy menstrual loss. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 2001; 108: 1222–8

Prentice A. Medical management of menorrhagia. BMJ 1999; 319: 1343–5

Coulter A, Kelland J, Peto V, et al. Treating menorrhagia in primary care: an overview of drug trials and survey of prescribing practice. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 1995; 11: 456–71

Lethaby A, Farquhar C, Cook I. Antifibrinolytics for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Systematic Review. Available in The Cochrane Library [database on disk and CD ROM]. Updated quarterly. The Cochrane Collaboration; issue. Oxford: Update Software, 2000

Rees MCP, DiMarzo V, Tippins JR, et al. Leukotreine release by endometrium and myometrium throughout the menstrual cycle in dysmenorrhoea and menorrhagia. J Endocrinol 1987; 113: 291–5

Rees MCP, Canete-Solar R, Lopez Bernal A, et al. Effects of fenamates on prostaglandin E receptor binding. Lancet 1988; II: 541–2

Cameron IT. Medical management of menorrhagia. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 1992; 2: 136–40

Anderson ABM, Hynes PJ, Guillebaud J, et al. Reduction of menstrual blood loss by prostaglandin synthetase inhibitors. Lancet 1976: 21: 774–6

Fraser IS, Pearse C, Shearman RP, et al. Efficacy of mefenamic acid in patients with a complaint of menorrhagia. Obstet Gynecol 1981; 58: 543–51

Fraser IS, McCarron G, Markham R, et al. Measured menstrual blood loss in women with menorrhagia associated with pelvic disease and coagulation disorder. Obstet Gynecol 1986; 68: 630–3

Fraser IS, McCarron G, Markham R, et al. Longterm treatment of menorrhagia with mefenamic acid. Obstet Gynecol 1983; 61: 109–12

Higham J, Shaw R. Risk-benefit assessment of drugs used for the treatment of menstrual disorders. Drug Saf 1991; 6(3): 183–91

Fraser IS. Treatment of ovulatory and anovulatory dysfunctional uterine bleeding with oral progestogens. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 1990; 30: 353–6

Stewart A, Cummins C, Gold L, et al. The effectiveness of levonorgestrel releasing intrauterine system in menorrhagia: a systematic review. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 2001; 108: 74–6

Lethaby AE, Cooke I, Rees M. Progesterone/progestogen releasing intrauterine systems versus either placebo or any other medication for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane systematic review. Available in The Cochrane Library [database on disk and CD ROM]. Updated quarterly. The Cochrane Collaboration; issue. Oxford: Update Software, 1999

Bhatena RK. Long acting progestogen-only contraceptive injections: an update. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 2001; 108: 3–8

Fraser IS, McCarron G. Randomised trial of 2 hormonal and 2 prostaglandin-inhibiting agents in women with complaints of menorrhagia. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 1991; 31: 66–70

Khastgir G, Studd J. Choice of treatment for menorrhagia. In: Seth S, Sutton C, editors. Menorrhagia. Oxford: Isis Medical Media, 1999: 299–315

Lethaby A, Augood C, Duckitt K. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Systematic Review. Available in The Cochrane Library [database on disk and CD ROM]. Updated quarterly. The Cochrane Collaboration; issue. Oxford: Update Software, 1998

Chamberlain G, Freeman R, Price F, et al. A comparative study of ethamsylate and mefenamic acid in dysfunctional uterine bleeding. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1991; 98: 707–11

Cameron IT, Haining R, Lumsden MA, et al. The effects of mefenamic acid and norethisterone on measured menstrual blood loss. Obstet Gynecol 1990; 76: 85–8

Cameron IT, Leask R, Kelly RW, et al. Effects of danazol, mefenamic acid, norethisterone and a progesterone-impregnated coil on endometrial prostaglandin concentrations in women with menorrhagia. Prostaglandins 1987; 34: 99–110

Dockeray CJ, Sheppard BL, Bonnar J. Comparison between mefenamic acid and danazol in the treatment of established menorrhagia. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1989; 96: 840–4

Grover V, Usha R, Gupta U, et al. Management of cyclical menorrhagia with prostaglandin synthetase inhibitor. Asia Oceania J Obstet Gynaecol 1990; 16: 255–9

Hall P, Maclachlan N, Thorn N, et al. Control of menorrhagia by the cyclo-oxygenase inhibitors naproxen sodium and mefenamic acid. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1987; 94: 554–8

Bonnar J, Sheppard B. Treatment of menorrhagia during menstruation: randomised controlled trial of ethamsylate, mefenamic acid and tranexamic acid. BMJ 1996; 313: 579–82

Edlund M, Anderson K, Rybo G, et al. Reduction of menstrual blood loss in women suffering from idiopathic menorrhagia with a novel antifibrinolytic drug (Kabi 2161). Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1995; 102: 913–7

Callender ST, Warner GT, Cope E. Treatment of menorrhagia with tranexamic acid: a double blind trial. BMJ 1970; 4: 214–6

Preston JT, Cameron IT, Adams EJ, et al. Comparative study of tranexamic acid and norethisterone in the treatment of ovulatory menorrhagia. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1995; 102: 401–5

Lethaby A, Irvine G, Cameron I. Cyclical progestogens for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane systematic review. Available in The Cochrane Library [database on disk and CD ROM]. Updated quarterly. The Cochrane Collaboration; issue. Oxford: Update Software, 1998

Milsom I, Anderson K, Andersch B, et al. A comparison of flurbiprofen, tranexamic acid and a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine contraceptive device in the treatment of idiopathic menorhagia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1991; 164: 879–83

Irvine GA, Campbell-Brown MB, Lumsden MA, et al. Randomised comparative trial of the levonorgestrel intrauterine system and norethisterone for treatment of idiopathic menorrhagia. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1998; 105(6): 592–8

Crosignani PG, Vercellini P, Mosconi P, et al. Levonorgestrel releasing intrauterine device versus hysteroscopic endometrial resection in treatment of dysfunctional uterine bleeding. Obstet Gynecol 1997; 90: 257–63

Kittleson N, Istre O. A randomised study comparing Levonorgestrel intrauterine system (LNG IUS) and transcervical resection of endometrium (TCRE) in the treatment of menorrhagia: preliminary results. Gynecol Endocrinol 1998; 7: 61–5

British National Formulary. British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. London 2002 Mar; 43: 475–6

Andersch B, Milsom I, Rybo G. An objective evaluation of flurbiprofen and tranexamic acid in the treatment of idiopathic menorrhagia. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1988; 67: 645–8

Effective Health Care. The management of menorrhagia. NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York, Research Unit, Royal College of Physicians 1995 (1)

Rybo G. Tranexamic acid therapy effective treatment in heavy menstrual bleeding: clinical update. Thera Adv 1991; 4: 1–8

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. The initial management of menorrhagia: RCOG evidence based clinical guidelines No. 1. London, 1998

Fender GRK, Prentice A, Gorst T, et al. Randomised controlled trial of educational package on management of menorrhagia in primary care: the Anglia Menorrhagia Education Study. BMJ 1999; 318: 1246–50

British National Formulary. British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. London 2002 Mar; 43: 123

Kovacs L, Falkay G. Ethamsylate as inhibitor of prostaglandin biosynthesys in pregnant human myometrium in-vitro. Experientia 1981; 37: 1182–3

Rennie JM, Lam PKL. Effects of ethamsylate on cerebral blood flow velocity in premature babies. Arch Dis Child 1989; 64: 46–7

Jaffe G, Wickham A. A double blind pilot study of dicynene in the control of menorrhagia. J Int Med Res 1973; 1: 127–9

Harrison RF, Campbell S. A double blind trial of ethamsylate in the treatment of primary and intra-uterine device menorrhagia. Lancet 1976; II: 283–5

Hickey M, Higham J, Fraser IS. Progestogens versus oestrogens and progestogens for irregular uterine bleeding associated with anovulation. Cochrane Systematic Review. Available in The Cochrane Library [database on disk and CD ROM]. Updated quarterly. The Cochrane Collaboration; issue. Oxford: Update Software, 1998

Bonduelle M, Walker JJ, Calder AA. A comparative study of danazol and norethisterone in dysfunctional uterine bleeding presenting as menorrhagia. Postgrad Med J 1991; 67: 833–6

Buyru F, Yalcin O, Kovanci E, et al. Danazol therapy in dysfunctional uterine bleeding [Turkish]. Istanbul Universitesi Tip Fakultesi Mecmuasi 1995; 58(3): 37–40

Higham JM, Shaw RW. A comparative study of danazol, a regimen of decreasing doses of danazol, and norethindrone in the treatment of objectively proven unexplained menorrhagia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1993; 169: 1134–9

British National Formulary. British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. London 2002 Mar; 43: 356

Bergqvist A, Rybo G. Treatment of menorrhagia with intrauterine release of progesterone. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1983; 90: 255–8

Van den Hurk PJ, O’Brien PMS. Non-contraceptive use of levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system. Obstet Gynecol 1999; 1(1): 13–9

Backman T, Huhtala S, Blom T, et al. Length and use of symptoms associated with premature removal of the levonorgestrel instruterine system: a nation-wide study of 17,360 users. BJOG. 2000; 107: 335–9

Lahteenmaki P, Haukkamaa M, Puolakka J, et al. Open randomised study of use of levonorgestrel releasing intrauterine system as alternative to hysterectomy. BMJ 1998; 316: 1122–6

Barrington JW, Bowen-Simpkins P. The levonorgestrel intrauterine system in the management of menorrhagia. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1997; 104: 614–6

British National Formulary. British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. London 2002; 43 Mar: 393–394

Hurskainen R, Teperi J, Rissanen P, et al. Quality of life and cost-effectiveness of levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system versus hysterectomy for treatment of menorrhagia: a randomised trial: early report. Lancet 2001; 357: 273–7

EuroQol Group. EuroQol: a new facility for the treatment of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 1990; 16: 199–208

British National Formulary. British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. London 2002 Mar; 43: 357

Working party on behalf of the National Health Committee. Guidelines for management of heavy menstrual bleeding. Wellington: National Health Committee, 1998

Nagrani R, Bowen-Simpkins P, Barrington JW. Can levonorgestrel intrauterine system replace surgical treatment for the management of menorrhagia? Br J Obstet Gynaecol 2002; 109: 345–7

The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. The management of menorrhagia in secondary care. National evidence-based clinical guidelines. RCOG, 1999

Belsey EM. Vaginal bleeding patterns among women using one natural and eight hormonal methods of contraception. Contraception 1988; 38: 181–206

Schwallie PC, Assenzo JR. Contraceptive use-efficacy study using depo-provera administered as an injection every 90 days. Fertil Steril 1973; 24: 331–42

Fraser IS. A survey of different approaches to management of menstrual disturbances in women using injectable contraceptives. Contraception 1983; 28: 385–97

Rowlands S, Dakin L. Twelve years of injectable contraceptive use in general practice. Br J Fam Plann 1998; 23: 133–4

Paul C, Skegg DC, Williams S. Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate: patterns of use and reasons for discontinuation. Contraception 1997; 56(4): 209–14

World Health Organisation. A multicentered phase III comparative clinical trial of depot-medroxyprogesterone acetate given three monthly at doses of 100mg or 150mg: contraceptive efficacy and side effects [abstract]. Contraception 1986; 34: 223

World Health Organisation. Multinational comparative evaluation of two long acting contraceptive steroids: norethisterone enanthate and medroxyprogesterone acetate: final report [abstract]. Contraception 1983; 28: 1

Cromer BA, Smith RD, Blair JM, et al. A prospective study of adolescents who chose among levonorgestrel implant, medroxy-progesterone acetate or the combined oral contraceptive pill as contraception. Pediatrics 1994; 94: 687–94

Amataykul K, Siarasonboon B, Thanangkul O. A study of mechanism of weight gain in medroxyprogesterone users. Contraception 1980; 22: 605–22

Matson SC, Henderson KA, McGrath GJ. Physical findings and symptoms of depot-medroxyprogesterone acetate use in adolescent females. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 1997; 10: 18–23

Cundy T, Evans M, Roberts H, et al. Bone density in women receiving depot medroxy progesterone for contraception. BMJ 1991; 303: 13–6

Guillebaud J. Oestrogen free hormonal contraception. In: Guillebaud J, editor. Contraceptions: your questions answered. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1999: 311–6, 328-9

Mishell Jr DR. Noncontraceptive health benefits of oral steroidal contraceptives. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1982; 142: 809–16

Iyer V, Farquhar C, Jepson R. Oral contraceptive pills for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Systematic Review. Available in The Cochrane Library [database on disk and CD ROM]. Updated quarterly. The Cochrane Collaboration; Issue 2. Oxford: Update Software, 1997

Nilsson L, Solvell L. Clinical studies in oral contraceptives: a randomised double blind crossover study of 4 different preparations. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1967; 46Suppl. 8: 1–31

Nilsson L, Rybo G. Treatment of menorrhagia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1971; 110: 713–20

Hefnawi F, Askalani H, Zaki K. Menstrual blood loss with copper intrauterine devices. Contraception 1974; 9: 133–9

Callard GV, Litofswky FS, De Merre LJ. Menstruation in women with normal or artificially controlled cycles. Fertil Steril 1966; 17: 684–8

Royal College of General Practitioners. Oral contraceptive and health. London: Pitman Medical, 1974

Ramacharan S, Pelligrin FA, Ray MR, et al. The Walnut Creek Contraceptive Drug Study: a prospective study of the side effects of oral contraceptives. Volume III. An interim report: a comparison of disease occurrence leading to hospitalisation or death in users or non users of oral contraceptives. J Reprod Med 1980; 25Suppl. 6: 345–72

British National Formulary. British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. London 2002 Mar; 43: 386–9

Gray RH. Patterns of bleeding associated with the use of steroidal contraceptives. In: Diczfalusy E, Fraser IS, Webb FTG, editors. Endometrial bleeding and steroidal contraception. Bath: Pitman Press, 1980: 14–49

Speroff L, Glass RH, Case N. Endometriosis. In: Speroff L, Glass RH, Case N, editors. Clinical gynaecologic endocrinology and infertility. 6th ed. Baltimore: Lippincot Williams & Wilkins, 1999: 1064

Barbieri RL, Osathanondh R, Ryan KJ. Danazol inhibition of steroidogenesis in human corpus luteum. Obstet Gynecol 1981; 57: 722–4

Need JA, Forbes KL, Millazzo L, et al. Danazol in the treatment of menorrhagia: the effect of 1 month induction dose (200mg) and 2 months of maintenance therapy (200mg, 100mg, 50mg or placebo). Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 1992; 32: 346–52

Chimbira TH, Anderson AB, Naish C, et al. Reduction of menstrual blood loss by danazol in menorrhagia: lack of effect of placebo. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1980; 87: 1152–8

Chimbira TH, Cope E, Anderson AB, et al. The effect of danazol on menorrhagia, coagulation mechanism, haematological indices and body weight. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1979; 86: 46–50

Beaumont H, Augood C, Duckitt K. Danazol for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane systematic review. Available in The Cochrane Library [database on disk and CD ROM]. Updated quarterly. The Cochrane Collaboration; issue. Oxford: Update Software, 2002

Lamb MP Danazol in menorrhagia: a double blind placebo controlled trial. J Obstet Gynaecol 1987; 7: 212–6

Wardle PG, Whitehead MI, Mills RP. Nonreversible and wide ranging vocal changes after treatment with danazol [abstract]. BMJ 1983; 287: 946

British National Formulary. British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. London 2002 Mar; 43: 372

British National Formulary. British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. London 2002 Mar; 43: 373

Turnbull AC, Rees MC. Gestrinone in the treatment of menorrhagia. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1990; 97: 713–5

Shaw RW, Duckitt K. Management of menorrhagia in women of childbearing age. In: Seth S, Sutton C, editors. Menorrhagia. Oxford: Isis Medical Media, 1999: 79–96

Shaw RW, Fraser HM. Use of superactive LHRH agonist in the treatment of menorrhagia. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1984; 91: 913–6

Miller RM, Frank RA. Zoladex in the treatment of benign gynaecological disorder: an overview of safety and efficacy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1992; 99Suppl. 7: 37–41

Thomas EJ, Okuda KJ, Thomas NM. Combination of GNRH agonist and cyclical HRT for DUB. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1991; 98: 1155–9

Lilford RJ. Hysterectomy: will it pay the bills in 2007 [editorial]. BMJ 1997; 314: 160–1

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Lynn Garden and Liz Grant for secretarial assistance. No sources of funding were used to assist in the preparation of this manuscript. The authors have no conflict of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Roy, S.N., Bhattacharya, S. Benefits and Risks of Pharmacological Agents Used for the Treatment of Menorrhagia. Drug-Safety 27, 75–90 (2004). https://doi.org/10.2165/00002018-200427020-00001

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00002018-200427020-00001