Abstract

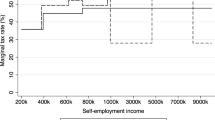

In this paper we present estimates of the responses of individuals to marginal tax rates in their reporting of income, using data from individual tax returns for the year 1995. One estimation method is ordinary least squares regression. A second method uses quantile regression, which provides evidence on behavioral responses at different points (or quantiles) in the distribution of income and so is relevant to the question of whether the responses of, say, the rich differ from those at other points in the income distribution. Our results clearly indicate that marginal tax rates affect the reporting decisions of individuals. However, there are significant differences in the marginal tax rate reporting responses for the various types of reported income, there are major differences across income classes, and there are notable differences in the estimated responses across estimation methods.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For example, Hausman (1981) estimates large compensated labor supply elasticities of primary and secondary workers, but MaCurdy et al. (1990) argue that these methods necessarily generate elasticities that overstate labor supply responses. Similarly large differences in estimated elasticities are present for individual responses to such tax policies as special savings incentives, charitable donations, housing choices, and capital gains realizations. For a discussion of many of these controversies, see Slemrod (1992).

As noted by Heckman (1996), the natural experiment approach imposes such restrictions as additive separability between the observed and unobserved variables and a special time series structure on unobserved variables. The natural experiment approach also requires that a “treatment group” and a “control group” be affected in identical ways by any changes that occur over the period of observation, except for the policy innovation. Even so, it is difficult to identify a specific feature of the policy innovation (e.g., a change in marginal tax rates) as the single driving force behind any behavioral response (e.g., a change in tax reporting behavior), since most policy changes typically include a number of other features.

For more detailed information on this data set, see Internal Revenue Service (1996).

Another limitation of the ITF is that the state identifier is not available for high-income individuals (or those with AGI over $200,000), so that the calculation of the state marginal tax rate is somewhat complicated for these individuals. However, totals by state for some items from the high-income returns are available in tabulated form from the IRS, and we are able to utilize these state tabulations to assign state identifiers for individuals with high income.

Capital gains income is notoriously sensitive to many factors including tax rates, state of the economy, other income, and the like. In our analysis, we exclude capital gains income from all calculations. In previous versions of our analysis, we included capital gains income, and found our results to be less robust. Especially for capital gains income, reporting behavior is complicated by life-cycle-induced realization behavior, and micro-level studies may be biased by their sensitivity to timing behavior.

An alternative approach is to use the exogenous variation in state income tax rates as an instrument to estimate the federal income tax rate. See, for example, Feenberg (1987).

We do not find Itemization to be endogenous, using the standard specification test.

Estimation of responses by quintile has a number of advantages. Since each quintile regression is based on taxpayers who lie within an income group, it is unlikely that marginal tax rates will be endogenous, although it should be noted this procedure yields separate samples with greatly reduced variation in the marginal tax rate. Separate estimation by income groups also allows for the exploitation of possible non-linearities in the responses of income reporting. Finally, responses estimated from quintiles are more targeted to specific income groups, unlike responses estimated from the entire sample that may not be pertinent for taxpayers far from the mean. The obvious disadvantage is that the variation in the marginal tax rate is substantially reduced within each quintile.

Note that the quantile ranking for, say, Wages and Salaries is based only upon Wages and Salaries income, not on Total Income. Consequently, the same individuals are not in the same quantiles for Wages and Salaries, AGI, or Total Income.

OLS estimation is most closely related to traditional empirical models that have estimated general taxpayer behavior. See, for example, the studies of how taxes affect labor supply, saving, charitable contributions, capital gains, and housing, in Slemrod (1992).

It should be noted that these other studies generally report income-tax price elasticities. It is straightforward to convert marginal tax rate elasticities to tax price elasticities. For example, recall that the income-marginal tax rate elasticity η is defined as \( \eta \equiv {\left[ {{\left( {{\partial R} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\partial R} {\partial t}}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} {\partial t}} \right)}{\left( {t \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {t R}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} R} \right)}} \right]} \). The corresponding income-tax price elasticity ɛ then equals \( \varepsilon \equiv {\left[ {{\left( {{\partial R} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\partial R} {\partial {\left( {1 - t} \right)}\left( {{{\left( {1 - t} \right)}} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{\left( {1 - t} \right)}} R}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} R} \right.}}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} {\partial {\left( {1 - t} \right)}\left( {{{\left( {1 - t} \right)}} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{\left( {1 - t} \right)}} R}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} R} \right.}} \right)}} \right]} = - \eta {\left[ {{{\left( {1 - t} \right)}} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{\left( {1 - t} \right)}} t}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} t} \right]} \).

For example, the use for all quantile elasticities of the median quantile values of the marginal tax rate and the respective income type generates elasticities that increase dramatically (in absolute size) with the quantile. The use of average values of the marginal tax rate and the income type generates a similar pattern of (large) elasticities.

References

Auten, G., & Carroll, R. (1999). The effect of income taxes on household behavior. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 81(4), 681–693.

Buchinsky, M. (1994). Changes in the U.S. wage structure, 1963–1987: Application of quantile regression. Econometrica, 61(4), 405–458.

Buchinsky, M. (1995). Estimating the asymptotic covariance matrix for quantile regression models: A Monte Carlo study. Journal of Econometrics, 68(3), 303–338.

DuMouchel, W. H., & Duncan, G. J. (1983). Using sample survey weights in multiple regression analyses of stratified samples. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 78(383), 535–543.

Feenberg, D. (1987). Are tax price models really identified: The case of charitable giving. National Tax Journal, 40(4), 629–633.

Feldstein, M. (1995). The effect of marginal tax rates on taxable income: A panel study of the 1986 Tax Reform Act. The Journal of Political Economy, 103(2), 551–576.

Gruber, J., & Saez, E. (2002). The elasticity of taxable income: Evidence and implications. Journal of Public Economics, 84(1), 1–32.

Hausman, J. A. (1981). Labor supply. In H. J. Aaron & J. A. Pechman (Eds.), How taxes affect economic behavior (pp. 27–72). Washington, DC.: The Brookings Institution.

Heckman, J. J. (1996). Comment. In M. Feldstein & J. M. Poterba (Eds.), Empirical foundations of household taxation (pp. 32–38). Chicago, IL: National Bureau of Economic Research and the University of Chicago Press.

Internal Revenue Service. (1996). 1995 Individual tax model file. Washington, DC.: Internal Revenue Service, Statistics of Income Division.

Koenker, R., & Basset, G. (1978). Regression quantiles. Econometrica, 46(1), 43–61.

MaCurdy, T., Green, D., & Paarsch, H. (1990). Assessing empirical approaches for analyzing taxes and labor supply. Journal of Human Resources, 25(2), 414–490.

Slemrod, J. (Ed.) (1992). Do taxes matter? The impact of the tax reform act of 1986. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Slemrod, J. (1998). Methodological issues in measuring and interpreting taxable income responses. National Tax Journal, 51(4), 773–788.

Slemrod, J. (2001). A general model of the behavioral response to taxation. International Tax and Public Finance, 8(2), 119–128.

Acknowledgement

We have benefited from helpful comments by the editor and an anonymous referee, as well as by Roy Bahl, Len Burman, Brian Erard, James Follain, Chih-Chin Ho, Alan Plumlee, and seminar and conference participants at Carleton University, Georgetown University, Georgia State University, the Statistics of Income Consultants Panel of the Internal Revenue Service, Syracuse University, the University of Colorado at Boulder, and the 60th International Atlantic Economic Conference in New York, NY, October 6–9, 2005.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Alm, J., Wallace, S. Which Elasticity? Estimating the Responsiveness of Taxpayer Reporting Decisions. Int Adv Econ Res 13, 255–267 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11294-007-9096-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11294-007-9096-9