Abstract

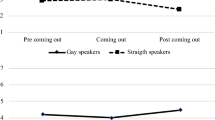

The purpose of this study was to investigate whether actors playing homosexual male characters in North-American television shows speak with a feminized voice, thus following longstanding stereotypes that attribute feminine characteristics to male homosexuals. We predicted that when playing homosexual characters, actors would raise the frequency components of their voice towards more stereotypically feminine values. This study compares fundamental frequency (F0) and formant frequencies (F i ) parameters in the speech of fifteen actors playing homosexual and heterosexual characters in North-American television shows. Our results reveal that the voices of actors playing homosexual male characters are characterized by a raised F0 (corresponding to a higher pitch), and raised formant frequencies (corresponding to a less baritone timbre), approaching values typical of female voices. Besides providing further evidence of the existence of an “effeminacy” stereotype in portraying male homosexuals in the media, these results show that actors perform pitch and vocal tract length adjustments in order to alter their perceived sexual orientation, emphasizing the role of these frequency components in the behavioral expression of gender attributes in the human voice.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Audibert, N., Aubergé, V., & Rilliard, A. (2010). Prosodic correlates of acted vs. spontaneous discrimination of expressive speech: a pilot study. In Proceedings from 5th International Conference on Speech Prosody. Chicago, USA.

Avery, J. D., & Liss, J. M. (1994). Acoustic characteristics of less-masculine-sounding male speech. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 99, 3738–3748.

Battles, G. K., & Hilton-Morrow, W. (2002). Gay characters in conventional spaces: Will and Grace and the situation comedy. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 19, 87–105.

Blashill, A. J., & Powlishta, K. K. (2009). Gay stereotypes: The use of sexual orientation as a cue for gender-related attributes. Sex Roles, 61, 783–793.

Boersma, P., & Weenink, D. (2009). PRAAT: Doing phonetics by computer (Version 5.1.19) [Computer program]. Retrieved from: http://www.praat.org.

Busby, P., & Plant, G. (1995). Formant frequency values of vowels produced by preadolescent boys and girls. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 97, 2603–2606.

Chuenwattanapranithi, S., Xu, Y., Thipakorn, B., & Maneewongvatana, S. (2006). Expressing anger and joy with the size code.In Proceedings of Speech Prosody. Dresden, Germany.

Chuenwattanapranithi, S., Xu, Y., Thipakorn, B., & Maneewongvatana, S. (2008). Encoding emotions in speech with the size code: A perceptual investigation. Phonetica, 65, 210–230.

Chung, S. K. (2007). Media literacy art education: Deconstructing lesbian and gay stereotypes in the media. International Journal of Art and Design Education, 26, 98–107.

Clopper, C., Pisoni, D. B., & Jong, K. (2005). Acoustic characteristics of the vowel systems of six regional varieties of American English. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 118, 1661–1676.

Costanzo, F. S., Markel, N. N., & Costanzo, P. R. (1969). Voice quality profile and perceived emotion. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 16, 267–270.

Davis, M. S. (1987). Acoustically mediated neighbor recognition in the North-American bullfrog, Rana-Catesbeiana. Behavioral Ecolology and Sociobiology, 21, 185–190.

Devillers, L., & Vasilescu, I. (2003). Prosodic cues for emotion characterization in real-life spoken dialogs. In Proceedings of Eurospeech (pp. 189–192).

Dow, B. (2001). Television, and the politics of gay and lesbian visibility. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 18, 123–140.

Drahota, A., Costall, A., & Reddy, V. (2008). The vocal communication of different kinds of smile. Speech Communication, 50, 278–287.

Fagel, S. (2010). Effect of smiled speech on lips, larynx and acoustics. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 5967, 294–303.

Fant, G. (1960). Acoustic theory of speech production. The Hague: Mouton and Co.

Feinberg, D. R., Jones, B. C., Little, A. C., Burt, D. M., & Perrett, D. I. (2005). Manipulations of fundamental and formant frequencies influence the attractiveness of human male voices. Animal Behaviour, 69, 561–568.

Fitch, W., & Giedd, J. (1999). Morphology and development of the human vocal tract: A study using magnetic resonance imaging. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 106, 1511–1522.

Fitch, W. T., & Reby, D. (2001). The descended larynx is not uniquely human. In Proceedings of the Royal Society. London, UK: Royal Society Publishing.

Frick, R. W. (1986). The prosodic expression of anger: Differentiating threat and frustration. Aggressive Behavior, 12, 121–128.

Gaudio, R. (1994). Sounding gay: Pitch properties in the speech of gay and straight men. American Speech, 96, 30–57.

Hajek, C., & Howard, G. (2005). Intergroup communication schemas: Cognitive representations of talk with gay men. Language & Communication, 25, 161–181.

Henton, C. G. (1989). Fact and fiction in the description of female and male pitch. Language & Communication, 9, 299–311.

Henton, C. G. (1995). Pitch dynamism in female and male speech. Language & Communication, 15, 43–61.

Hillenbrand, J. M., Getty, L. A., Clark, M. J., & Wheeler, K. (1995). Acoustic characteristics of American English vowels. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 97, 3099–3111.

Hodges-Simeon, C. R., Gaulin, S. J. C., & Puts, D. A. (2010). Different vocal parameters predict perceptions of dominance and attractiveness. Human Nature, 21, 406–427.

Hollien, H., Green, R., & Massey, K. (1994). Longitudinal research on adolescent voice change in males. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 96, 2646–2654.

Johnson, W. F., Emde, R. N., Scherer, K. R., & Klinnert, M. D. (1986). Recognition of emotion from vocal cues. Archives of General Psychiatry, 43, 280–283.

Kienast, M., & Sendlmeier, W. F. (2000). Acoustical analysis of spectral and temporal changes in emotional speech. In Proceedings from the ISCA ITRW on Speech and Emotion. Newcastle, UK: Textflow.

Kite, M. E., & Deaux, K. (1987). Gender belief systems: Homosexuality and the implicit inversion theory. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 11, 83–96.

Ko, S. J., Judd, C. M., & Blair, I. V. (2006). What the voice reveals: Within- and between-category stereotyping on the basis of voice. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32, 806–819.

Lasarcyk, E., & Trouvain, J. (2003). Spread lips + raised larynx + higher F0 = smiled speech?: An articulatory synthesis approach. In Proceedings of the 8th International Seminar on Speech Production. Strasbourg, France: INRIA.

Lee, S., Potamianos, A., & Narayanan, S. (1999). Acoustics of children’s speech: Developmental changes of temporal and spectral parameters. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 105, 1455–1468.

Linneman, T. J. (2008). How do you solve a problem like Will Truman? The feminization of gay masculinities on Will and Grace. Men and Masculinities, 10, 583–603.

Lopez, P. T., Narins, P. M., Lewis, E. R., & Moore, S. W. (1988). Acoustically induced call modification in the white-lipped frog, Leptodactylus albilabris. Animal Behavior, 36, 1295–1308.

Madon, S. (1997). What do people believe about gay males? A study of stereotype content and strength. Sex Roles, 37, 663–685.

Mattingly, I. G. (1966). Speaker variation and vocal-tract Size (A). The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 39, 1219(A).

Munson, B., & Babel, M. (2007). Loose lips and silver tongues, or, projecting sexual orientation through speech. Language and Linguistics Compass, 1, 416–449.

Munson, B., McDonald, E., & DeBoe, N. (2006). The acoustic and perceptual bases of judgments of women and men’s sexual orientation from read speech. Journal of Phonetics, 24, 202–240.

Murray, I. R., & Arnott, J. L. (1993). Toward the simulation of emotion in synthetic speech: A review of the literature on human vocal emotion. Journal of Acoustic Society of America, 93, 1097–1106.

Ohala, J. J. (1984). An ethological perspective on common cross-language utilization of F0 of voice. Phonetica, 41, 1–16.

Perry, T., Ohde, R., & Ashmead, D. (2001). The acoustic bases for gender identification from children’s voices. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 109, 2988–2998.

Pierrehumbert, J., Bent, T., & Munson, B. (2004). The influence of sexual orientation on vowel production (L). The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 116, 1905–1908.

Pisanski, K., & Rendall, D. (2011). The prioritization of voice fundamental frequency or formants in listeners’ assessments of speaker size, masculinity, and attractiveness. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 129, 2201–2212.

Plant, R. L., & Younger, R. M. (2000). The interrelationship of subglottic air pressure, fundamental frequency, and vocal intensity during speech. Journal of Voice, 14, 170–177.

Puts, D., Gaulin, S., & Verdolini, K. (2006). Dominance and the evolution of sexual dimorphism in human voice pitch. Evolution and Human Behavior, 27, 283–296.

Puts, D. A., Hodges, C. R., Cárdenas, R. A., & Gaulin, S. J. C. (2007). Men’s voices as dominance signals: Vocal fundamental and formant frequencies influence dominance attributions among men. Evolution and Human Behavior, 28, 340–344.

Raley, A. B., & Lucas, L. J. (2006). Stereotype or success? Prime-time television’s portrayals of gay male, lesbian, and bisexual characters. Journal of Homosexuality, 51, 19–38.

Reby, D., & McComb, K. (2003). Anatomical constraints generate honesty: Acoustic cues to age and weight in the roars of red deer stags. Animal Behavior, 65, 519–530.

Reby, D., McComb, K., Cargnelutti, B., Darwin, C., & Fitch, W. T. (2005). Red deer stags use formants as assessment cues during intrasexual agonistic interactions. London: Proceedings of the Royal Society, Royal Society Publishing.

Rendall, D., Kollias, S., Ney, C., & Lloyd, P. (2005). Pitch (F0) and formant profiles of human vowels and vowel-like baboon grunts: The role of vocalizer body size and voice-acoustic allometry. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 117, 944–955.

Rendall, D., Vasey, P., & McKenzie, J. (2008). The Queen’s english: An alternative, biosocial hypothesis for the distinctive features of “gay speech”. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 37, 188–204.

Riordan, C. J. (1977). Control of vocal-tract length in speech. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 62, 998–1002.

Sachs, J., Lieberman, P., & Erikson, D. (1973). Anatomical and cultural determinants of male and female speech. In R. W. Shuy & R. W. Fasold (Eds.), Language attitudes (pp. 74–84). Washington: Georgetown University Press.

Simpson, A. P. (2009). Phonetic differences between male and female speech. Language and Linguistics Compass, 3, 621–640.

Smith, D. R. R., & Patterson, R. D. (2005). The interaction of glottal-pulse rate and vocal-tract length in judgments of speaker size, sex, and age. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 118, 3177–3186.

Smyth, R., Jacobs, G., & Rogers, H. (2003). Male voices and perceived sexual orientation: An experimental and theoretical approach. Language in Society, 32, 329–350.

Staats, G. R. (1978). Stereotype content and social distance: Changing views of homosexuality. Journal of Homosexuality, 4, 15–27.

Sundberg, J., & Nordstrom, P. E. (1976). Raised and lowered larynx: The effect on vowel formant frequencies. Speech Transmission Laboratory Quarterly Progress, 17, 35–39.

Tartter, V. C. (1980). Happy talk: Perceptual and acoustic effects of smiling on speech. Perception & Psychophysics, 27, 24–27.

Terengo, L. (1966). Pitch and duration characteristics of the oral reading of males on a masculinity-femininity dimension. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 9, 590–595.

Thomas, E. R. (2003). Secrets revealed by southern vowel shifting. American Speech, 78, 150–170.

Titze, I. R. (1994). Principles of voice production. Iowa City: IA7 National Center for Voice and Speech.

Tivoli, M., & Gordon, M. J. (2008). The [+ spread] of the Northern Cities Shift. In University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics. (Vol. 14, pp. 111–120).

Tom, K., Titze, I. R., & Hoffman, E. A. (2001). Three-dimensional vocal tract imaging and formant structure: Varying vocal register, pitch, and loudness. The Journal of Acoustical Society of America, 109, 742–747.

Vorperian, H. K., & Kent, R. D. (2007). Vowel acoustic space development in children: A synthesis of acoustic and anatomic data. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 50, 1510–1545.

Vorperian, H. K., Kent, R. D., & Lindstrom, M. J. (2005). Development of vocal tract length during early childhood: A magnetic resonance imaging study. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 117, 338–350.

Wolfe, V. I., Ratusnik, D. L., Smith, F. H., & Northrop, G. (1990). Intonation and fundamental frequency in male-to-female transsexual. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 55, 43–50.

Wondershare Software Co. Ltd. (2010). iSkysoft Audio Ripper (Version 1.8.2.7) [Computer program]. Retrieved from: http://www.iskysoft.com.

Wyatt, D. A. (2008). Gay/lesbian/bisexual television characters. [Website] Retrieved from: http://home.cc.umanitoba.ca/~wyatt/tv-characters.html.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Karen McComb and Robin Banerjee for their helpful comments on earlier versions of the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1

Calculation of Formant Spacing

Formant spacing (ΔF) was calculated by fitting a model that assumes that the vocal tract is an open (lips)—closed (glottis) tube with a uniform cross-section (quarter-wave resonator) to the observed formant values (Reby and McComb 2003). In this model individual formant frequencies are inversely related to the length of the vocal tract by the following formula:

where c is the speed of sound in air (approximated as 350 m/s in the vocal tract), i is the number of the formant (i = 1, 2,…) and VTL is the length of the vocal tract (Titze 1994).

Since the formant frequency spacing can be expressed as the difference between any two adjacent formants, ΔF is inversely related to VTL:

By replacing VTL in Eq. (1) with ∆F estimated in Eq. (2), individual formants are directly related to ∆F:

Thus, ∆F can be derived from Eq. (3) as the slope of the linear regression of observed formant frequency values Fi (y-axis) over the expected formant positions (2i−1)/2 (x-axis), and with the intercept set to 0 (Reby and McComb 2003).

Appendix 2

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cartei, V., Reby, D. Acting Gay: Male Actors Shift the Frequency Components of Their Voices Towards Female Values When Playing Homosexual Characters. J Nonverbal Behav 36, 79–93 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10919-011-0123-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10919-011-0123-4