Published online Nov 28, 2010. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i44.5621

Revised: August 30, 2010

Accepted: September 7, 2010

Published online: November 28, 2010

AIM: To study the value of neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) for advanced gastric cancer by performing a meta-analysis of the published studies.

METHODS: All published controlled trials of NAC for advanced gastric cancer vs no therapy before surgery were searched. Studies that included patients with metastases at enrollment were excluded. Databases included Cochrane Library of Clinical Comparative Trials, MEDLINE, Embase, and American Society of Clinical Oncology meeting abstracts from 1978 to 2010. The censor date was up to April 2010. Primary outcome was the odds ratio (OR) for improving overall survival rate of patients with advanced gastric cancer. Secondary outcome was the OR for down-staging tumor and increasing R0 resection in patients with advanced gastric cancer. Safety analyses were also performed. All calculations and statistical tests were performed using RevMan 5.0 software.

RESULTS: A total of 2271 patients with advanced gastric cancer enrolled in 14 trials were divided into NAC group (n = 1054) and control group (n = 1217). The patients were followed up for a median time of 54 mo. NAC significantly improved the survival rate [OR = 1.27, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.04-1.55], tumor stage (OR = 1.71, 95% CI: 1.26-2.33) and R0 resection rate (OR = 1.51, 95% CI: 1.19-1.91) of patients with advanced gastric cancer. No obvious safety concerns were raised in these trials.

CONCLUSION: NAC can improve tumor stage and survival rate of patients with advanced gastric cancer with a rather good safety.

- Citation: Li W, Qin J, Sun YH, Liu TS. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer: A meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(44): 5621-5628

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v16/i44/5621.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i44.5621

Gastric cancer is still a major health problem and a leading cause of cancer-related death although its incidence is decreased worldwide[1]. Surgery is the only curative treatment modality for gastric cancer and the overall survival (OS) rate of early-stage gastric cancer patients is up to 90%[2]. However, as the majority of gastric cancer patients are at the advanced stage at the time of diagnosis, their overall prognosis is suboptimal despite aggressive treatment, with an overall survival rate of 20%-30% after radical surgical resection in Europe and about 60% in Japan[3,4]. Clearly, effective adjuvant therapy is needed to improve the outcome of patients with advanced gastric cancer.

Adjuvant therapy for gastric cancer has been extensively studied[2,5,6]. The effect of adjuvant chemoradiation therapy and perioperative chemotherapy has been demonstrated in well designed, multicenter and randomized clinical trials. It was recently reported that adjuvant chemotherapy has an affirmative effect on locally advanced gastric cancer[5]. S-1, an oral fluoropyrimidine (Taiho Pharmaceutical) used as an adjuvant chemotherapeutic agent, can increase 10% 3-year overall survival rate of patients with gastric cancer[6]. Among the potential strategies for adjuvant therapy, preoperative chemotherapy may provide an equal therapeutic efficacy as postoperative chemotherapy for gastric cancer[7]. Chemotherapy delivery may be more efficient if given prior to surgical disruption of vasculature, tumor down-staging may substantially facilitate surgical resection[8], and preoperative chemotherapy can be used to evaluate tumor chemosensitivity to cytotoxic medications. Furthermore, gastric cancer patients may tolerate preoperative cytotoxic treatment better than postoperative treatment, as performance status is usually negatively impacted by surgery[9]. However, lack of response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) may delay curative surgery and chemotherapy-induced toxicity may increase surgical complications[10].

The effect of NAC on gastric cancer has been studied in several prospective trials[11-14]. However, no definite conclusion has been drawn from these trials. The underlying reasons included insufficient statistical power due to a limited sample size, an extended period of time for patient accrual, imbalanced treatment arms, and non-protocol treatment strategy. A well-designed randomized clinical trial is therefore needed to define the effect of NAC on advanced gastric cancer. A relatively effective alternative to provide clinical evidence under such circumstances is to perform a meta-analysis of the published clinical trials[15]. The current meta-analysis was to evaluate the role of NAC in treatment of gastric cancer and explore the optimal strategy for chemotherapy delivery.

All published controlled trials comparing NAC vs no treatment before surgery in patients with locally advanced gastric cancer were included in our analysis. Blindness of the trial was not necessary. The inclusion criteria were patients with pathologically diagnosed gastric adenocarcinoma and no history of prior treatment before entering the trial but a history of potentially curative surgery. A study was chosen if it was updated. NAC was performed through oral or intravenous (IV), intraperitoneal (IP) and intra-arterial (IA) infusion. Studies on preoperative radiotherapy or immunotherapy were excluded. Postoperative therapies were not included in our study.

Primary outcome was the odds ratio (OR) of intervention with overall survival rate. Secondary outcome was the OR of R0 resection rates and tumor down-staging, which was represented as the percentage in stage pT0-2 after surgery. If the 95% confidence interval (CI) of the OR included 1.0, no difference was considered between the groups. Subgroup analysis was used to explore and explain the differences in results of different studies. Sensitivity analysis was also performed to show the publication bias.

Cochrane archives of clinical comparative trials, MEDLINE, Embase and American Society of Clinical Oncology meetings were retrieved from 1978 to 2010, with a censor date up to April 2010. The search strategy terms used in the English databases were “neoadjuvant chemotherapy OR preoperative chemotherapy” AND “gastric cancer OR stomach cancer OR stomach neoplasm OR gastric carcinoma” AND “clinical trial”. Trials published in journals or published as meeting abstracts with essential data were included. Non-controlled trials were excluded. Randomized controlled trials with three or more arms were retained if at least two arms addressed an eligible comparison. Studies on patients with metastatic gastric cancer at enrollment were excluded.

Methodological quality of trials was evaluated according to the Jadad quality scores[16], which include secure method of randomization, allocation concealment, patient and observer blinding, and losses to follow-up. Based on these criteria, the studies were divided into high quality group (score ≥ 4) and low quality group (score < 4). Two reviewers independently assessed the eligibility of each trial.

Authors, year of publication, country of investigators, sample size (total, eligible, and per arm), chemotherapy regimen, cycles of chemotherapy, follow-up period, curative effect (survival rate, rate of macroscopic radical resection cancer stage at pathological examination), and adverse events of each eligible trial were recorded. Two reviewers independently made extracts from each study.

RevMan software 5.0 was employed for the meta-analysis[17]. Continuous data were expressed as weighted mean difference. OR for dichotomous parameters including overall survival rate, tumor down-staging, and R0 resection rate was recorded. Results were reported as 95% CI. All meta-analyses appraised inter-study heterogeneity using χ2-based Q statistics for statistical significance and I2 statistics for the degree of heterogeneity. P < 0.10 was considered statistically significant and I2 > 50% showed a large heterogeneity. If there was no heterogeneity, a fixed-effect model was used. Otherwise, a random-effect model was used. The number needed to treat (NNT) was applied for outcomes with a statistical difference. Publishing bias was tested using the funnel plot. Sensitivity analysis was performed to investigate the possible influence of the study quality on the results. The main outcome of high-quality trials was analyzed. Subgroup analysis was used to explore and explain the diversity in results of different studies for collecting information with different characteristics, such as tumor grade, chemotherapy regimen, and race.

A total of 354 studies were retrieved. After abstracts were read, 335 studies were found to be unrelated to our selection criteria and it was impossible to extract data from another 5 studies. Thus, only 14 studies[18-31] were eligible for our meta-analysis. The enrolled 2271 gastric cancer patients in the studies were divided into NAC group (n = 1054) and control group (n = 1217). Of the 14 studies, 9 were from Asian and 5 from Western countries. NAC routes were IV, IA, IP, and oral in 7, 2, 1, and 4 studies, respectively. The median follow-up time of the patients across the studies was 54 mo (Table 1). The quality of included studies was assessed according to the Jadad quality scores[16] for the 4 requirements (method of randomization, allocation concealment, blindness, and completeness of follow up). Accordingly, 6 studies had a score greater than 4 (high quality, low risk of bias)[18-21,24,30] (Table 2).

| Author and year of publication (citation) | Country | Patients (n) | NAC group | Control group | Median follow-up (mo) | |||

| NAC | Control | Pre-op | Post-op | Pre-op | Post-op | |||

| Schuhmacher et al[18], 2009 | Germany | 72 | 72 | 5-FU + DDP | None | None | None | 53 |

| Boige et al[19], 2007 | France | 113 | 111 | FP | FP | None | None | 68 |

| Cunningham et al[20], 2006 | UK | 250 | 253 | ECF | ECF | None | None | 47 |

| Hartgrink et al[21], 2004 | Holland | 27 | 29 | FAMTX | None | None | None | 83 |

| Nio et al[22], 2004 | Japan | 102 | 193 | UFT (oral) | CT | None | CT | 83 |

| Zhang et al[23], 2004 | China | 37 | 54 | IV (no details) | None | None | None | NR |

| Kobayashi et al[24], 2000 | Japan | 91 | 80 | 5-FU (oral) | CT | None | None | NR |

| Wang et al[25], 2000 | China | 30 | 30 | 5-FU (oral) | None | None | None | NR |

| Takiguchi et al[26], 2000 | Japan | 123 | 139 | 5-FU ± DDP | None | None | None | NR |

| Lygidakis et al[27], 1999 | Greece | 39 | 19 | IP (no details) | CT | None | None | NR |

| Kang et al[28], 1996 | Korea | 53 | 54 | PEF | PEF | None | PEF | > 36 |

| Masuyama et al[29], 1994 | Japan | 24 | 98 | EAP (IA) | None | None | None | > 36 |

| Yonemura et al[30], 1993 | Japan | 29 | 26 | PMUE | None | None | PMUE | 24 |

| Nishioka et al[31], 1982 | Japan | 64 | 59 | 5-FU (oral) | CT | None | CT | > 60 |

| Author and year of publication (citation) | Randomization | Allocation concealment | Blind | Withdrawal and dropout | Jadad score |

| Schuhmacher et al[18], 2009 | Without details | Without details | Without details | Well reported | 4 |

| Boige et al[19], 2007 | Without details | Without details | Without details | Well reported | 4 |

| Cunningham et al[20], 2006 | Well reported | Envelope | Double-blind | Well reported | 7 |

| Hartgrink et al[21], 2004 | Well reported | Envelope | No | Well reported | 5 |

| Nio et al[22], 2004 | Inappropriate | None | No | Well reported | 1 |

| Zhang et al[23], 2004 | Without details | None | No | Well reported | 2 |

| Kobayashi et al[24], 2000 | Well reported | Envelope | No | Well reported | 5 |

| Wang et al[25], 2000 | Without details | Without details | No | Well reported | 3 |

| Takiguchi et al[26], 2000 | Without details | None | No | Well reported | 2 |

| Lygidakis et al[27], 1999 | Inappropriate | Without details | No | Well reported | 2 |

| Kang et al[28], 1996 | Without details | Without details | No | Well reported | 3 |

| Masuyama et al[29], 1994 | Inappropriate | None | No | Well reported | 1 |

| Yonemura et al[30], 1993 | Well reported | Envelope | No | Well reported | 5 |

| Nishioka et al[31], 1982 | Inappropriate | None | No | Well reported | 1 |

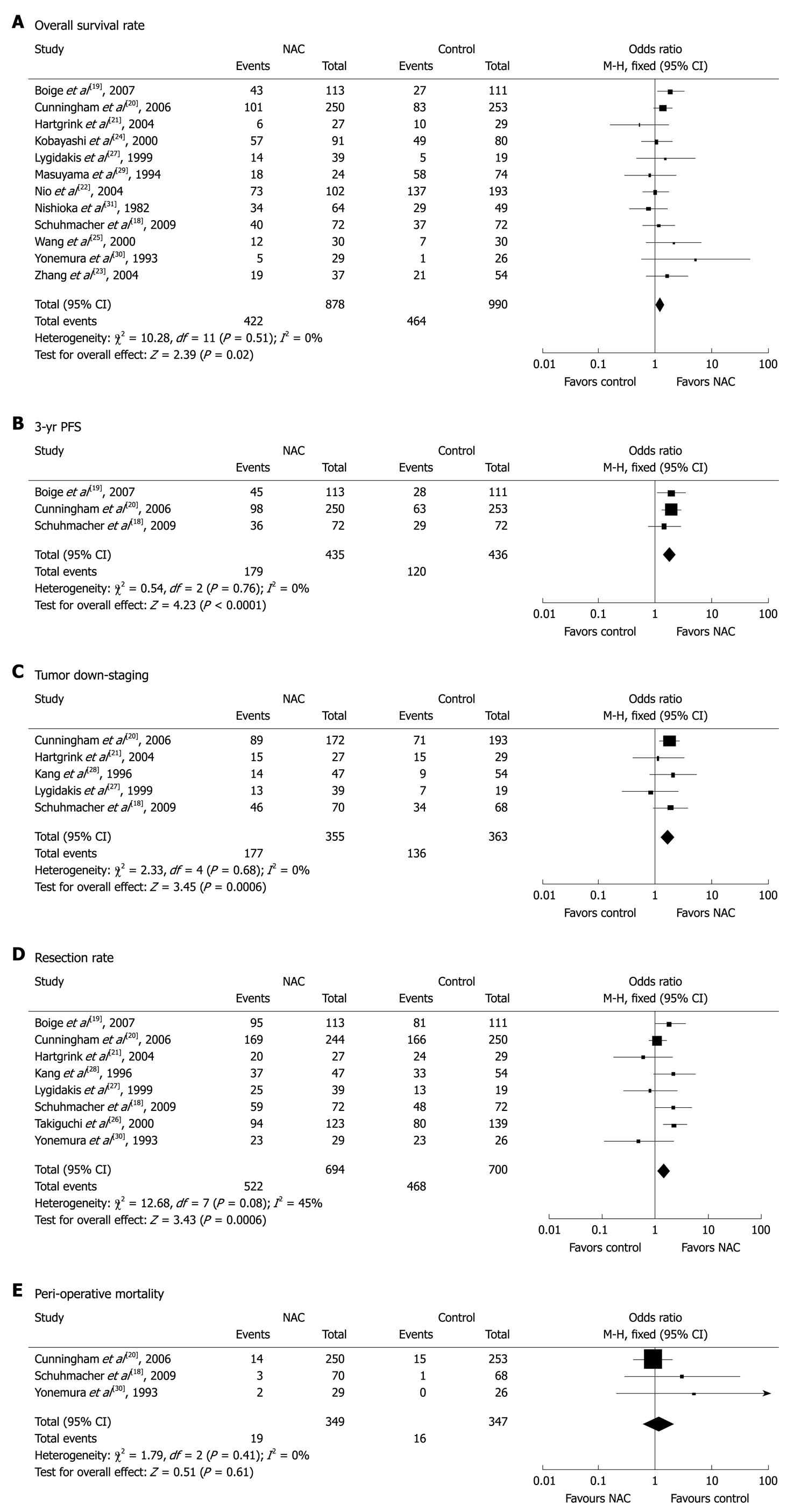

Twelve studies[18-25,27,29-31] with 1868 patients (878 in NAC group and 990 in control group) reported survival rates at the end of follow-up. The median follow-up time in these studies was over 3 years. The NAC group had a marginal survival benefit compared to the control group (48.1% vs 46.9%, respectively), with an OR of 1.27 (95% CI: 1.04-1.55, fixed-effect model) and a NNT of 84 (Figure 1A).

Three studies[18-20] compared the 3-year progression-free survival (PFS) rates for the two groups. The 3-year PFS rate was higher for NAC group than for control group (41.1% vs 27.5%), with an OR of 1.85 (95% CI: 1.39-2.46, fixed-effect model) and a NNT of 8 (Figure 1B).

Six studies[18,20-22,27,28] described the pathological staging of gastric cancer after resection. Except for one study[22] showing non-comparative staging data at baseline from the two groups, the other 5 studies involving 718 patients (355 in NAC group and 363 in control group) were included in the final analysis. The rate of pT0-2 was higher for NAC group than for control group (49.9% vs 37.5%), suggesting that NAC has a significant down-staging effect on gastric cancer with an OR of 1.71 (95% CI: 1.26-2.33) and a NNT of 9 (Figure 1C).

The resection rate of gastric cancer was reported in 8 trials[18-21,26-28,30]. Since no obvious heterogeneity was observed in these studies (P = 0.08, I2 = 45%), the fixed-effect model was used. The R0 resection rate of gastric cancer was higher for NAC group than for control group (75.2% vs 66.9%) with an OR of 1.51 (95% CI: 1.19-1.91, fixed-effect model) (Figure 1D).

Safety analysis included both chemotherapy-induced adverse effects (grade 3/4, defined according to the Common Toxicity Criteria of the National Cancer Institute, version 2.0) and perioperative morbidity and mortality. Three studies[20,22,30] reported grade 3/4 adverse effects of NAC, including gastrointestinal (GI) problems in 8.8% (31/353) and leukopenia in 18.1% (62/343) of gastric cancer patients. Three studies[18,20,30] reported perioperative mortality with no statistically significant difference (P = 0.61) between the two groups (5.4% vs 4.6%, Figure 1E).

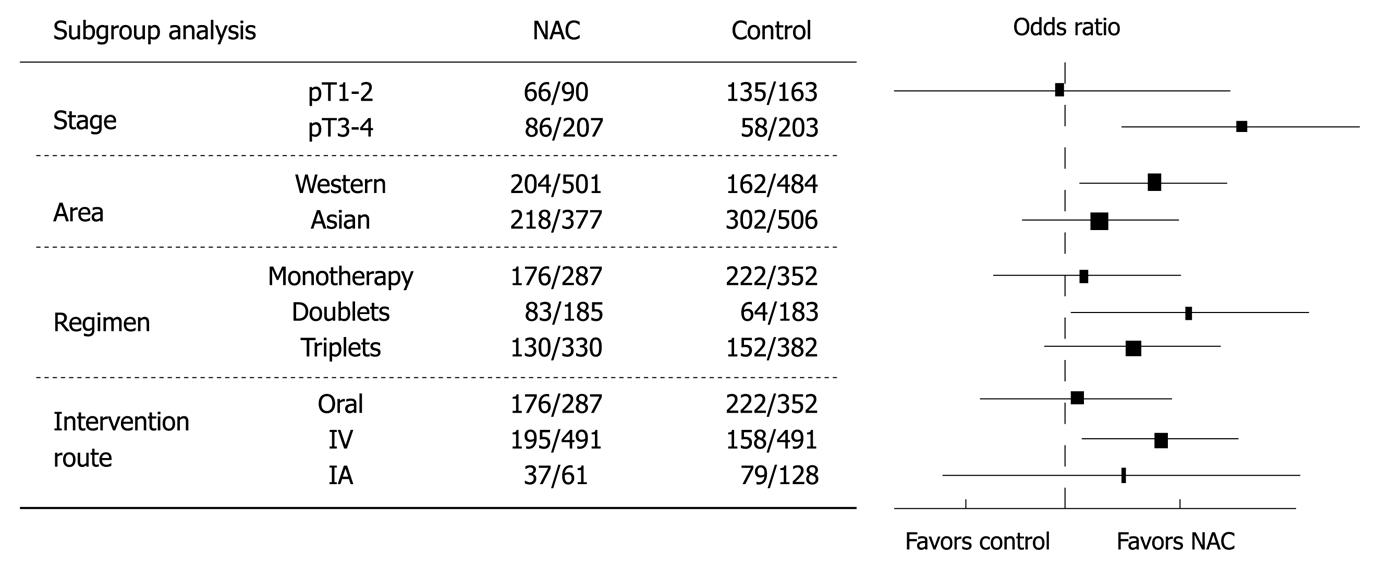

Different factors that might be related to the different results between the two groups were studied (Figure 2). When the overall survival rate was set as the end point, gastric cancer patients at a later stage (pT3-4) benefited more from NAC than those at an earlier stage (pT1-2) (OR = 1.91, 95% CI: 1.24-2.96, NNT = 8). Trials from Western countries showed more solid data favoring NAC than those from Asian countries (OR = 1.39, 95% CI: 1.07-1.80). Monotherapy regimens were inferior to doublet or triplet chemotherapy regimens (OR = 1.05, 95% CI: 0.75-1.48). IV route of NAC was better than other routes (OR = 1.42, 95% CI: 1.08-1.85).

Our current meta-analysis demonstrated the feasibility of NAC for locally advanced gastric cancer. NAC could down-stage (NNT = 9) and increase the R0 rate of gastric cancer. However, whether NAC improves the overall survival rate of gastric cancer patients is still controversial[5]. To examine the role of NAC alone in improving the overall survival rate of gastric cancer patients who did not receive postadjuvant chemotherapy, data from the 5 trials[18,21,23,25,29] were further analyzed, showing that NAC has no effect on the overall survival rate of gastric cancer patients (OR = 1.20, 95% CI: 0.8-1.80). Since all the included studies had a very small sample size (17-123 patients in the NAC arms) with a different follow-up time, no clear conclusion could be reached on the effect of NAC alone on overall survival rate of gastric cancer patients.

Our meta-analysis showed that gastric cancer patients could well tolerate NAC. Preoperative chemotherapy was feasible as over 80% patients with advanced gastric cancer completed all treatment courses, except for one trial where only 55.6% of the patients completed all courses[21]. Grade 3/4 GI adverse events of NAC occurred in 8.8% (31/353) of gastric cancer patients, which is considerably lower than that (25%) induced by postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy[32]. The tolerance to postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy was often marred by surgery-related GI effects. No severe and obvious postoperative complications, such as anastomotic leakage, infection, or death, occurred after NAC, indicating that NAC is a safe modality for gastric cancer.

Overtreatment of early gastric cancer with NAC is a potential concern. Whether later stage gastric cancer (T3-4) is the optimal group for NAC was analyzed. A Japanese trial[2] on serosa-negative cancer including node-positive disease showed that the 5-year disease-free survival rate and overall survival rate are 83% and 86%, respectively for gastric cancer patients receiving D2 surgery (gastrectomy with extended lymph-node dissection), indicating that early-stage gastric cancer patients may be cured with adequate surgical therapy alone rather than with NAC. Subgroup analysis also showed that the outcome of NAC for gastric cancer was better in trials from Western countries than in those from Asian countries. Of the 14 trials included in the present study, 6 were from Japan that included more patients with gastric cancer diagnosed at an earlier stage, thus possibly influencing the final results.

One of the questions concerning NAC for gastric cancer is its best regimen. Great efforts have been made on finding the optimal NAC for gastric cancer. In our current meta-analysis, few data were available to answer this question. However, our analysis showed that combination regimen and IV route of NAC had a high efficiency on advanced gastric cancer. Theoretically, NAC with a high response rate can be recommended for metastatic gastric cancer. For example, docetaxel-based[33] or epirubicin-based triple therapy[34] is a good option for metastatic gastric cancer. Regimens with a rapid and high response rate help to down-stage tumors to the greatest extent and increase the probability of R0 resection, thus improving the survival rate for patients with gastric cancer.

Disease progression during NAC is another potential concern due to a loss of opportunity for surgery. In our meta-analysis, two trials[18,22] showed a disease progression rate of 2.9% (4/138). Of the 402 patients with gastric cancer, 108 (26.9%) in NAC group underwent palliative resection (n = 76) or with their tumor unresectable (n = 32), which was lower than that (33.8%) in control group[18,20-22,30], indicating that disease progression after NAC is not a major concern for its resection.

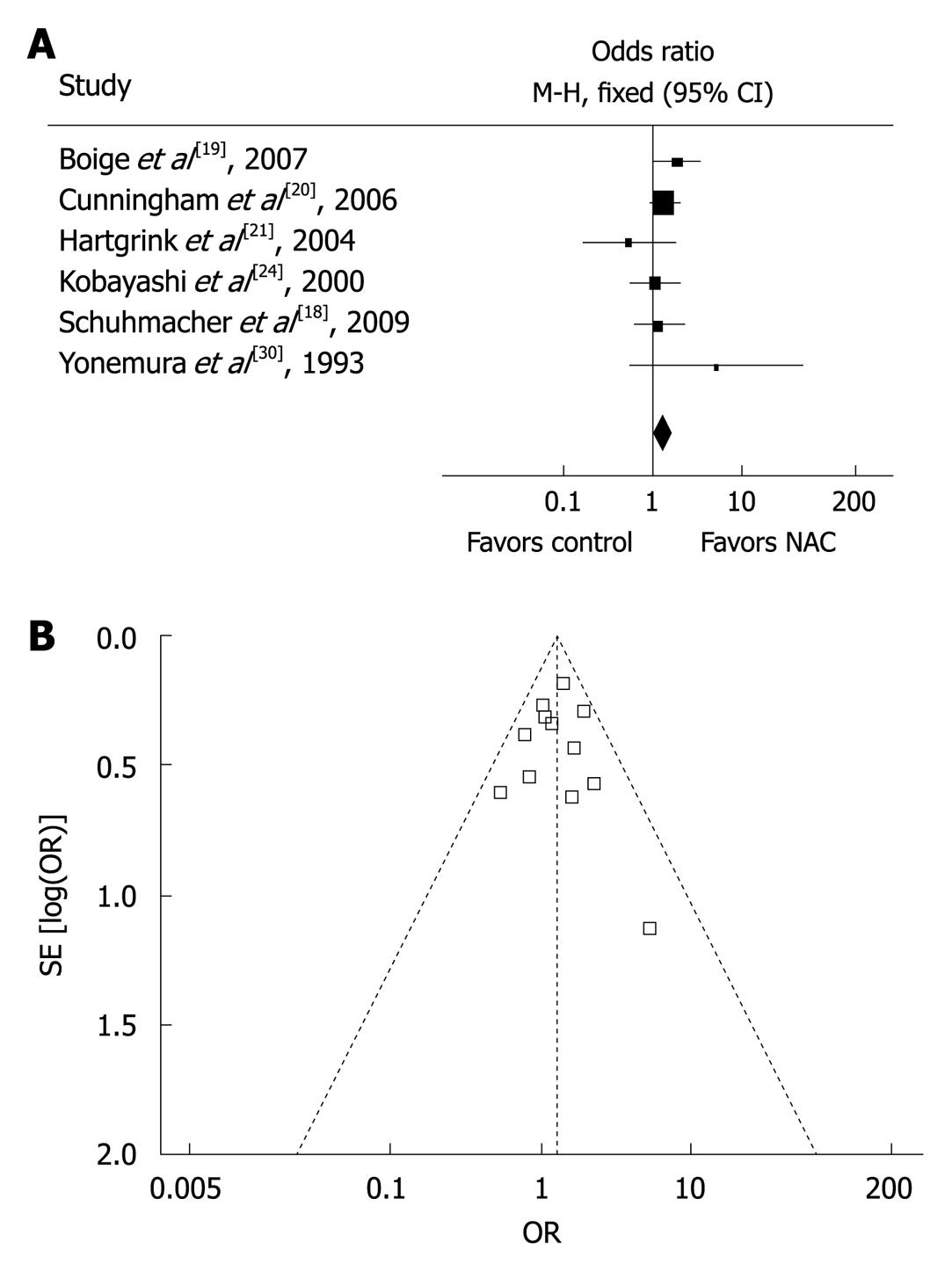

A major concern in our meta-analysis was the quality of studies included. Since no sufficient randomized controlled trials were available on NAC for gastric cancer, our current meta-analysis included quasi-randomized or non-randomized but controlled trials with basic data that could be used for comparison. Sensitivity analysis was therefore performed to determine the effect of trial quality on the final results. Six high-quality trials with a Jadad score ≥ 4[18-21,24,30] reported the overall survival rate with an OR of 1.35 (95% CI: 1.06-1.73) compared to that with an OR of 1.27 (95% CI: 1.04-1.55) in all the studies (Figure 3A), indicating that the results are consistent with those in all the trials and are therefore independent of trial quality. Furthermore, the symmetrical shape of ‘funnel plot’ when drawing together survival rate and sample size for all the studies indicated that no obvious publication bias was found in our meta-analysis (Figure 3B).

NAC has been proven effective against some cancers, such as breast cancer[35]. However, it is not generally recommended for gastric cancer, primarily because of differences in treatment modalities for gastric cancer between Asian and Western countries. A Western study demonstrated that D2 surgery can effectively remove lymph nodes[36], whereas a Japanese study showed that D2 surgery is highly effective and safe, and recommended as a routine surgery[4]. It was reported that chemoradiotherapy is the standard therapy for gastric cancer after operation in USA[37] and most appropriate for the D0 dissection population. Whether post-chemoradiotherapy benefits D2 dissection patients lacks strong evidence. It has been shown that perioperative chemotherapy can prolong the survival time of locally advanced gastric cancer patients who tolerate preoperative chemotherapy better than postoperative chemotherapy[20]. Therefore, NAC is a hopefully good option for locally advanced gastric cancer, although further studies are required to determine its best regimen.

Our meta-analysis provided the up-to-date evidence for the positive effect of NAC on locally advanced gastric cancer. A number of new trials have been registered to examine the role of NAC in treatment of advanced gastric cancer, such as S-1 plus cisplatin[38]. Our meta-analysis should therefore be further updated whenever new and strong evidence is available. With the increasing acceptance of the concept of NAC, additional studies on new regimens and well-designed powerful trials are highly encouraged in patients with locally advanced gastric cancer.

Over 50% of patients with newly diagnosed gastric cancer have advanced disease. Even after surgery, their prognosis remains poor. The effect of chemotherapy on advanced gastric cancer has been proven. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) plays a role in improving the prognosis of advanced gastric cancer patients, but its value remains controversial because of lack of well-powered trials.

Meta-analysis was used to evaluate the value of NAC for advanced gastric cancer in this study.

The meta-analysis provided the up-to-date evidence for the positive effect of NAC on locally advanced gastric cancer. NAC improved the R0 resection rate (95% CI: 1.19-1.91), tumor down-staging (95% CI: 1.26-2.33) and survival rate (95% CI: 1.04-1.55) for the 2271 patients enrolled in 14 trials. No obvious safety concerns were raised in these trials. These findings suggest that NAC can improve the survival rate of patients with advanced gastric cancer.

With the increasing acceptance of the concept of NAC, additional studies on new regimens and well-designed powerful trials are highly encouraged in patients with locally advanced gastric cancer.

MAGIC trial: A phase III clinical trial conducted by the Medical Research Council Adjuvant Gastric Infusional Chemotherapy, showing the effect of perioperative chemotherapy on advanced gastric cancer. INT-0116 study: The Intergroup-0116 study reporting that postoperative chemoradiotherapy is effective against gastric adenocarcinoma or gastroesophageal junction. D2 surgery: D2 lymphadenectomy which was defined according to the rules of the Japanese Research Society for Gastric Cancer and, therefore, included all lymphnodes of levels N1 and N2. Adverse events: Assessed according to the Common Toxicity Criteria of the National Cancer Institute (version 2.0) and defined as grade 0-4. Tumor stage: Assessed according to the International Union against Cancer: TNM classification of malignant tumors. “pT” indicates the pathological stage after surgery and “cTNM” indicates the clinical pretreatment tumor stage. S-1: An orally active combination of tegafur (a prodrug that is converted by cells to fluorouracil), gimeracil (an inhibitor of dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase, which degrades fluorouracil), and oteracil (which inhibits the phosphorylation of fluorouracil in the gastrointestinal tract, thereby reducing the gastrointestinal toxic effects of fluorouracil) with a molar ratio of 1:0.4:1.

This is an important analysis of NAC for advanced gastric cancer. The meta-analysis of all available controlled trials on NAC conduced by the authors may provide the up to date evidence of NAC for advanced gastric cancer.

Peer reviewer: Greger Lindberg, MD, PhD, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Karolinska University Hospital, K63, Stockholm, SE-14186, Sweden

S- Editor Sun H L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Lin YP

| 1. | Kamangar F, Dores GM, Anderson WF. Patterns of cancer incidence, mortality, and prevalence across five continents: defining priorities to reduce cancer disparities in different geographic regions of the world. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2137-2150. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Nashimoto A, Nakajima T, Furukawa H, Kitamura M, Kinoshita T, Yamamura Y, Sasako M, Kunii Y, Motohashi H, Yamamoto S. Randomized trial of adjuvant chemotherapy with mitomycin, Fluorouracil, and Cytosine arabinoside followed by oral Fluorouracil in serosa-negative gastric cancer: Japan Clinical Oncology Group 9206-1. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2282-2287. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Degiuli M, Sasako M, Ponti A, Calvo F. Survival results of a multicentre phase II study to evaluate D2 gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:1727-1732. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Sano T, Sasako M, Yamamoto S, Nashimoto A, Kurita A, Hiratsuka M, Tsujinaka T, Kinoshita T, Arai K, Yamamura Y. Gastric cancer surgery: morbidity and mortality results from a prospective randomized controlled trial comparing D2 and extended para-aortic lymphadenectomy--Japan Clinical Oncology Group study 9501. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2767-2773. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Paoletti X, Oba K, Burzykowski T, Michiels S, Ohashi Y, Pignon JP, Rougier P, Sakamoto J, Sargent D, Sasako M. Benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy for resectable gastric cancer: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010;303:1729-1737. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Sakuramoto S, Sasako M, Yamaguchi T, Kinoshita T, Fujii M, Nashimoto A, Furukawa H, Nakajima T, Ohashi Y, Imamura H. Adjuvant chemotherapy for gastric cancer with S-1, an oral fluoropyrimidine. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1810-1820. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Wilke H, Preusser P, Fink U, Gunzer U, Meyer HJ, Meyer J, Siewert JR, Achterrath W, Lenaz L, Knipp H. Preoperative chemotherapy in locally advanced and nonresectable gastric cancer: a phase II study with etoposide, doxorubicin, and cisplatin. J Clin Oncol. 1989;7:1318-1326. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Urschel JD, Vasan H, Blewett CJ. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials that compared neoadjuvant chemotherapy and surgery to surgery alone for resectable esophageal cancer. Am J Surg. 2002;183:274-279. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Forshaw MJ, Gossage JA, Mason RC. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for oesophageal cancer: the need for accurate response prediction and evaluation. Surgeon. 2005;3:373-382, 422. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Weber WA, Ott K, Becker K, Dittler HJ, Helmberger H, Avril NE, Meisetschläger G, Busch R, Siewert JR, Schwaiger M. Prediction of response to preoperative chemotherapy in adenocarcinomas of the esophagogastric junction by metabolic imaging. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3058-3065. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Takahashi T, Saikawa Y, Yoshida M, Kitagawa Y, Otani Y, Kubota T, Kumai K, Kitajima M. A pilot study of combination chemotherapy with S-1 and low-dose cisplatin for highly advanced gastric cancer. Anticancer Res. 2006;26:1631-1635. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Barone C, Cassano A, Pozzo C, D'Ugo D, Schinzari G, Persiani R, Basso M, Brunetti IM, Longo R, Picciocchi A. Long-term follow-up of a pilot phase II study with neoadjuvant epidoxorubicin, etoposide and cisplatin in gastric cancer. Oncology. 2004;67:48-53. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Persiani R, Rausei S, Pozzo C, Biondi A, Barone C, Cananzi FC, Schinzari G, D'Ugo D. 7-Year survival results of perioperative chemotherapy with epidoxorubicin, etoposide, and cisplatin (EEP) in locally advanced resectable gastric cancer: up-to-date analysis of a phase-II study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:2146-2152. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Kinoshita T, Sasako M, Sano T, Katai H, Furukawa H, Tsuburaya A, Miyashiro I, Kaji M, Ninomiya M. Phase II trial of S-1 for neoadjuvant chemotherapy against scirrhous gastric cancer (JCOG 0002). Gastric Cancer. 2009;12:37-42. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | Phillips B, Ball C, Sackett D, Badenoch D, Straus S, Haynes B, Dawes M, Howick J. Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine - Levels of Evidence (March 2009). Available from: http://www.cebm.net/index.aspx?o=1025. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 16. | Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1-12. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 17. | Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Version 5.0.1 (Updated September 2008). The Cochrane Collaboration. 2008; Available from: http://www.cochrane-handbook.org. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 18. | Schuhmacher C, Schlag P, Lordick F, Hohenberger W, Heise J, Haag C, Gretschel S, Mauer ME, Lutz M, Siewert JR. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy versus surgery alone for locally advanced adenocarcinoma of the stomach and cardia: Randomized EORTC phase III trial #40954. J Clin Oncol (Meeting Abstracts). 2009;27:4510. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Boige V, Pignon J, Saint-Aubert B, Lasser P, Conroy T, Bouché O, Segol P, Bedenne L, Rougier P, Ychou M. Final results of a randomized trial comparing preoperative 5-fluorouracil (F)/cisplatin (P) to surgery alone in adenocarcinoma of stomach and lower esophagus (ASLE): FNLCC ACCORD 07-FFCD 9703 trial [Abstract]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4510. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 20. | Cunningham D, Allum WH, Stenning SP, Thompson JN, Van de Velde CJ, Nicolson M, Scarffe JH, Lofts FJ, Falk SJ, Iveson TJ. Perioperative chemotherapy versus surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:11-20. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 21. | Hartgrink HH, van de Velde CJ, Putter H, Songun I, Tesselaar ME, Kranenbarg EK, de Vries JE, Wils JA, van der Bijl J, van Krieken JH. Neo-adjuvant chemotherapy for operable gastric cancer: long term results of the Dutch randomised FAMTX trial. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2004;30:643-649. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 22. | Nio Y, Koike M, Omori H, Hashimoto K, Itakura M, Yano S, Higami T, Maruyama R. A randomized consent design trial of neoadjuvant chemotherapy with tegafur plus uracil (UFT) for gastric cancer--a single institute study. Anticancer Res. 2004;24:1879-1887. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 23. | Zhang CW, Zou SC, Shi D, Zhao DJ. Clinical significance of preoperative regional intra-arterial infusion chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:3070-3072. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 24. | Kobayashi T, Kimura T. [Long-term outcome of preoperative chemotherapy with 5'-deoxy-5-fluorouridine (5'-DFUR) for gastric cancer]. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 2000;27:1521-1526. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 25. | Wang XL, Wu GX, Zhang MD, Guo M, Zhang H, Sun XF. A favorable impact of preoperative FPLC chemotherapy on patients with gastric cardia cancer. Oncol Rep. 2000;7:241-244. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 26. | Takiguchi N, Oda K, Suzuki H, Wakatsuki K, Nunomora M, Kouda K, Saito N, Nakajima N. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) or low dose cis-platinum (CDDP) + 5-FU in the treatment of gastric carcinoma with serosal invasion. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2000;19:A1178. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 27. | Lygidakis NJ, Sgourakis G, Aphinives P. Upper abdominal stop-flow perfusion as a neo and adjuvant hypoxic regional chemotherapy for resectable gastric carcinoma. A prospective randomized clinical trial. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46:2035-2038. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 28. | Kang YK, Choi DW, Im YH, Kim CM, Lee JI, Moon NM, Lee JO. A phase III randomized comparison of neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgery versus surgery for locally advanced stomach cancer. Abstract 503 presented at the ASCO Annual Meeting. 1996; Available from: http://www.asco.org/ASCOv2/Meetings/Abstracts?&vmview=abst_detail_view&confID=29&abstractID=10042. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 29. | Masuyama M, Taniguchi H, Takeuchi K, Miyata K, Koyama H, Tanaka H, Higashida T, Koishi Y, Mugitani T, Yamaguchi T. [Recurrence and survival rate of advanced gastric cancer after preoperative EAP-II intra-arterial infusion therapy]. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 1994;21:2253-2255. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 30. | Yonemura Y, Sawa T, Kinoshita K, Matsuki N, Fushida S, Tanaka S, Ohoyama S, Takashima T, Kimura H, Kamata T. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for high-grade advanced gastric cancer. World J Surg. 1993;17:256-261; discussion 261-262. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 31. | Nishioka B, Ouchi T, Watanabe S, Umehara M, Yamane E, Yahata K, Muto F, Kojima O, Nomiyama S, Sakita M. [Follow-up study of preoperative oral administration of an antineoplastic agent as an adjuvant chemotherapy in stomach cancer]. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 1982;9:1427-1432. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 32. | Liu TS, Wang Y, Chen SY, Sun YH. An updated meta-analysis of adjuvant chemotherapy after curative resection for gastric cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2008;34:1208-1216. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 33. | Van Cutsem E, Moiseyenko VM, Tjulandin S, Majlis A, Constenla M, Boni C, Rodrigues A, Fodor M, Chao Y, Voznyi E. Phase III study of docetaxel and cisplatin plus fluorouracil compared with cisplatin and fluorouracil as first-line therapy for advanced gastric cancer: a report of the V325 Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4991-4997. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 34. | Cunningham D, Starling N, Rao S, Iveson T, Nicolson M, Coxon F, Middleton G, Daniel F, Oates J, Norman AR. Capecitabine and oxaliplatin for advanced esophagogastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:36-46. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 35. | Untch M, von Minckwitz G. Recent advances in systemic therapy: advances in neoadjuvant (primary) systemic therapy with cytotoxic agents. Breast Cancer Res. 2009;11:203. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 36. | Hartgrink HH, van de Velde CJ, Putter H, Bonenkamp JJ, Klein Kranenbarg E, Songun I, Welvaart K, van Krieken JH, Meijer S, Plukker JT. Extended lymph node dissection for gastric cancer: who may benefit? Final results of the randomized Dutch gastric cancer group trial. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2069-2077. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 37. | Macdonald JS, Smalley SR, Benedetti J, Hundahl SA, Estes NC, Stemmermann GN, Haller DG, Ajani JA, Gunderson LL, Jessup JM. Chemoradiotherapy after surgery compared with surgery alone for adenocarcinoma of the stomach or gastroesophageal junction. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:725-730. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 38. | Satoh S. S-1 and cisplatin in treating patients who are undergoing surgery for stage III stomach cancer,. Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT00182611. [Cited in This Article: ] |