Summary

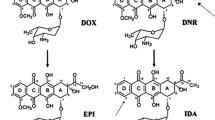

Anthracyclines are widely used and effective antineoplastic drugs. Although active against a wide variety of solid tumours and haematological malignancies, their clinical use is hindered by tumour resistance and toxicity to healthy tissue. Modification of the general anthracycline ring structure results in analogues with different but overlapping antitumour and tolerability profiles.

Activity of the anthracyclines is related to topoisomerase II inhibition, which occurs as a result of anthracycline intercalation between adjacent DNA base pairs. Production of hydroxyl free radicals is associated with antitumour effects and toxicity to healthy tissues. Myocardial tissue is particularly susceptible to free radical damage. Development of tumour cell resistance to anthracyclines involves a number of mechanisms, including P-glycoprotein-mediated resistance.

The classical dose-limiting adverse effects of this class of drugs are acute myelosuppression and cumulative dose-related cardiotoxicity. Anthracycline-induced cardiomyopathy is often irreversible and may lead to clinical congestive heart failure. Other toxicities of the anthracyclines, including stomatitis, nausea and vomiting, alopecia and ‘radiation recall’ reactions, are generally reversible.

Anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity may be reduced or prevented by an administration schedule that produces low peak plasma drug concentrations. Administration of dexrazoxane also provides cardioprotection. Dose intensification of anthracyclines may partly overcome resistance but is associated with reduced tolerability.

Liposomal encapsulation of doxorubicin or daunorubicin alters the pharmacokinetic properties of the drugs. Increased distribution in tumours, prolonged circulation and reduced free drug concentrations in plasma may increase antitumour activity and improve the tolerability of the anthracyclines.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Mross K. New anthracycline derivatives: what for? Eur J Cancer 1991; 27(12): 1542–4

Weiss RB. The anthracyclines: will we ever find a better doxorubicin? Semin Oncol 1992; 19(6): 670–86

Booser DJ, Hortobágyi GN. Anthracycline antibiotics in cancer therapy: focus on drug resistance. Drugs 1994; 47(2): 223–58

Abraham R, Basser RL, Green MD. A risk-benefit assessment of anthracycline antibiotics in antineoplastic therapy. Drug Saf 1996; 15(6): 406–29

Meriweather VD, Bachur NR. Inhibition of DNA and RNA metabolism by daunorubicin and adriamycin in L1210 mouse leukemia. Cancer Res 1972; 32: 1137–42

Reinert KE. Anthracycline-binding induced DNA stiffening, bending and elongation: stereochemical implications from viscometric investigations. Nucleic Acids Res 1983; 11: 3411–40

Sinha BK, Katki AG, Batist G, et al. Adriamycin-stimulated hydroxyl formation in human breast tumour cells. Biochem Pharmacol 1987; 36: 793–6

Dorr RT. Cytoprotective agents for anthracyclines. Semin Oncol 1996; 23Suppl. 8: 23–34

Larsson R, Nygren P. Cytotoxic activity of topoisomerase II inhibitors in primary cultures of tumor cells from patients with human hematologic and solid tumors. Cancer 1994; 74: 2857–62

Efferth T, Osieka R. Clinical relevance of the MDR-1 gene and its gene product, P-glycoprotein, for cancer chemotherapy: a meta-analysis. Tumor Diagn Ther 1993; 14: 238–43

Goldhirsch A, Wood WC, Senn H-J. Meeting highlights: international consensus panel on the treatment of primary breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 1995; 87: 1441–5

Anon. Novantrone for prostate cancer in the US. Scrip 1996 Nov 26; 17 (No. 2184)

Wiernik PS, Glidewell WJ, Hoagland HL, et al. A comparative trial of daunomycin, ara-c, thioguanine and a combination of the 3 agents for the treatment of acute myelocytic leukaemia. Med Pediatr Oncol 1979; 6: 261–77

Yates JW, Glidewell O, Wiernik P, et al. Cytosine-arabinoside with daunorubicin or adriamycin for therapy of acute myelocytic leukemia: a CALGB study. Blood 1982; 60: 454–62

Vogler WR, Velez-Garcia E, Weiner RS, et al. A phase III trial comparing idarubicin and daunorubicin in combination with cytarabine in acute myelogenous leukemia: a South Eastern Cancer Study Group study. J Clin Oncol 1992; 10: 1102–11

Bassan R, Lerede T, Rambaldi A. The role of anthracyclines in adult acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Leukemia 1996; 10Suppl. 2: S58–61

Levine M, Bramwell V, Bowman D, et al. A clinical trial of intensive CEF versus CMF in premenopausal women with node positive breast cancer [abstract]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1995; 14: 103

Launchbury AP, Habboubi N. Epirubicin and doxorubicin: a comparison of their characteristics, therapeutic activity and toxicity. Cancer Treat Rev 1993; 19: 197–228

Deveaux Y, Mathelin C, Al-Homsi S, et al. Cyclophosphamide (CPM), 5-fluorouracil (5FU) and either doxorubicin (DOX) or theprubicine (THP) (FAC vs FTP) in advanced breast cancer (ABC) — a phase III randomised study [abstract no. 319]. Eur J Cancer 1991; 27Suppl. 2: S58

Hortobágyi GN, Theriault RL, Frye D, et al. Pirarubicin in combination chemotherapy for metastatic breast cancer. Am J Clin Oncol 1990; 13Suppl. 1: S54–6

Henderson IC, Allegra JC, Woodcock T. Randomised clinical trial comparing mitoxantrone with doxorubicin in previously treated patients with metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 1989; 7: 560–71

Twelves CJ. Oral idarubicin in solid tumour chemotherapy. Clin Drug Invest 1995; 9Suppl. 2: 39–54

Bennett JM, Muss HB, Doroshow JF, et al. A randomized multicenter trial comparing mitoxantrone, cyclophosphamide, and fluorouracil with doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and fluorouracil in the therapy of metastatic breast carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 1988; 6: 1611–20

Leonard RCF, Cornbleet MA, Kaye SB, et al. Mitoxantrone versus doxorubicin in combination chemotherapy for advanced carcinoma of the breast. J Clin Oncol 1987; 5: 1056–63

Neidhart JA, Gochnour D, Roach R, et al. A comparison of mitoxantrone and doxorubicin in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 1986; 4: 672–7

Martoni A, Piana E, Guaraldi M, et al. Comparative phase II study of idarubicin versus doxorubicin in advanced breast cancer. Oncology 1990; 47: 427–32

Lopez M, Contegiacomo A, Vici P, et al. A prospective randomized trial of doxorubicin versus idarubicin in the treatment of advanced breast cancer. Cancer 1989; 64: 2431–6

A’Hern RP, Gore ME. Impact of doxorubicin on survival in advanced ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol 1995; 13: 726–32

Zuckerman KS. Efficacy of intensive, high-dose anthracyclinebased therapy in intermediate- and high-grade non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. Semin Oncol 1994; 21Suppl. 1: 59–64

Perry MC. Complications of chemotherapy. In: Moosa AR, Schimpff SC, Robson MC, editors. Comprehensive textbook of oncology. 2nd ed. Baltimore, Maryland: Williams & Wilkins, 1991: 1706–19

Shan K, Lincoff AM, Young JB. Anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity. Ann Intern Med 1996; 125: 47–58

von Hoff DD, Layard MW, Basa P, et al. Risk factors for doxorubicin-induced congestive heart failure. Ann Intern Med 1979 Nov; 91: 710–7

Coukell AJ, Faulds D. Epirubicin: an updated review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic efficacy in the management of breast cancer. Drugs 1997; 53(3): 453–82

Legha S, Benjamin RS, Mackay B, et al. Reduction of doxorubicin cardiotoxicity by prolonged continuous IV infusion. Ann Intern Med 1982; 96: 133–9

Bielack SS, Erttman R, Kempg-Bielack B, et al. Impact of scheduling on toxicity and clinical efficacy of doxorubicin: what do we know in the mid-nineties? Eur J Cancer 1996; 32A: 1652–60

Helleman K. Anthracycline cardiac toxicity by dexrazoxane: breakthrough of a barrier — sharpens antitumour profile and therapeutic index [editorial]. J Clin Oncol 1996; 14(2): 332–3

Venturini M, Michelotti A, Del Maestro L, et al. Multicenter randomized controlled clinical trial to evaluate cardioprotection of dexrazoxane versus no cardioprotection in women receiving epirubicin chemotherapy for advanced breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 1996; 14: 3112–20

Physicians’ Desk Reference. Zinecard™. Medical Economics Company, Montvale, NJ, USA; 1996: 1961–3

Kim S. Liposomes as carriers of cancer chemotherapy: current status and future prospects. Drugs 1993; 46(4): 618–38

Allen TM. Liposomes: opportunities in drug delivery. Drugs 1997; 54Suppl. 4: 8–14

Gabizon AA, Martin F. Polyethylene-glycol-coated (pegylated) liposomal doxorubicin: rationale for use in solid tumours. Drugs 1997; 54Suppl. 4: 15–21

Muggia F. Clinical efficacy and prospects for use of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in the treatment of ovarian and breast cancers. Drugs 1997; 54Suppl. 4: 22–9

Alberts D, Garcia DJ. Safety aspects of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in patients with cancer. Drugs 1997; 54Suppl. 4: 30–35

Gabizon AA. Liposomal anthracyclines. Hematol Oncol Clin N Amer 1994; 8(2): 431–50

Schuller J, Czejka M, Bandak S, et al. Comparison of pharmacokinetics (PK) of free and liposome encapsulated doxorubicin in advanced cancer patients. Onkologie 1995; 18Suppl. 2: 184

Ahmad I, Longnecker M, Samuel J, et al. Antibody-targeted delivery of doxorubicin entrapped in sterically stabilized liposomes can eradicate lung cancer in mice. Cancer Res 1993; 53: 1484–8

Allen TM, Brandeis E, Hansen CB, et al. A new strategy for attachment of antibodies to sterically stabilized liposomes resulting in efficient targeting to cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Acta 1995; 1237: 99–108

Coukell AJ, Spencer CM. Liposomal doxorubicin: a review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic efficacy in the management of patients with AIDS-related Kaposi’s sarcoma. Drugs 1997; 53(3): 520–38

Gill PS, Wernz J, Scadden DT, et al. Randomized phase III trial of liposomal daunorubicin versus doxorubicin, bleomycin, and vincristine in AIDS-related Kaposi’s sarcoma. J Clin Oncol 1996; 14: 2353–64

Muggia FM, Hainsworth JD, Jeffers S, et al. Phase II study of liposomal doxorubicin in refractory ovarian cancer: antitumour activity and toxicity modification by liposomal encapsulation. J Clin Oncol 1997; 15: 987–93

Hupperets PSGJ, Erdkamp FLG, Ten Bokkel-Huinink WW, et al. Phase II study of liposomal encapsulated daunorubicin (DaunoXome) in advanced breast cancer [abstract 244]. Breast Canc Res Treat 1996; 37 Suppl.: 76

Lippens R. Liposomal daunorubicin in childhood brain tumors, preliminary results of a phase II study [abstract no. 4032]. Can J Infect Dis 1995; 6Suppl. C: 440C

Schmoll E, Degen H. Liposomal daunorubicin (LD) in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [abstract no. 308]. Onkologie 1995; 18Suppl. 2: 96

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hortobágyi, G.N. Anthracyclines in the Treatment of Cancer. Drugs 54 (Suppl 4), 1–7 (1997). https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-199700544-00003

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-199700544-00003