Key Points

-

The need for blood transfusions in wartime and the emerging threat of infection from blood and blood products have motivated several commercial companies to develop compounds that aim to substitute for the oxygen-transport function of blood.

-

At present, there are two classes of such 'blood substitutes' under active development: haemoglobin-based oxygen carriers (HBOCs) and fluorocarbon-based oxygen carriers (FBOCs). As the most widely explored approach for the development of blood substitutes has been the adaptation of haemoglobin (Hb), this review focuses on HBOCs.

-

Hb in adult red-blood cells (RBCs) is a tetramer of two α and two β polypeptide chains. An iron-containing haem prosthetic group is buried in a hydrophobic pocket in each chain and is capable of carrying one oxygen molecule per haem.

-

A variety of HBOCs with chemical or genetic modifications that are intended to stabilize Hb outside its natural environment — red blood cells (RBCs) — in a functional tetrameric and/or polymeric form have been developed.

-

However, because of the initial success in manufacturing, and preclinical and clinical testing in normal healthy volunteers, little attention was paid to the inner working of the Hb molecule, or to the effects of chemical and/or genetic modifications on the integrity and stability of the protein.

-

There have now been several well-publicized setbacks in clinical trials of HBOCs. Hb outside its natural protective environment (that is, RBCs) is toxic owing to the fact that Hb is a redox-active molecule. Central to this activity is the haem group — it undergoes redox transition to higher oxidation states with increasing redox reactivity towards biological molecules, leading to tissue toxicity.

-

Chemical and/or genetic modifications of Hb can suppress or enhance these reactions. So, one can design against these reactions by restricting the haem reactivity with biological molecules. Exploring endogenous protective mechanisms and/or inclusion of antioxidants in Hb solutions might also provide some protection against Hb oxidative toxicities.

Abstract

Chemically modified or genetically engineered haemoglobins (Hbs) developed as oxygen therapeutics (often termed 'blood substitutes') are designed to correct oxygen deficit due to ischaemia in a variety of clinical settings. These modifications are intended to stabilize Hb outside its natural environment — red blood cells — in a functional tetrameric and/or polymeric form. Uncontrolled haem-mediated oxidative reactions of cell-free Hb and its reactions with various oxidant/antioxidant and cell signalling systems have emerged as an important pathway of toxicity. Current protective strategies designed to produce safe Hb-based products are focused on controlling or suppressing the 'radical' nature of Hb while retaining its oxygen-carrying function.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Stowell, C. P., Levin, J., Spiess, B. D. & Winslow, R. M. Progress in the development of RBC substitutes. Transfusion 41, 287–299 (2001).

Leveton, L. R., Sox, H. C. Jr & Stoto, M. HIV and the Blood Supply: An Analysis of Crisis Decision-making (National Academy Press, Washington DC, 1995).

Dickerson, R. E. & Geis, I. Hemoglobin: Structure, Function, Evolution, and Pathology (Benjamin Cummings, Amsterdam, 1983).

Haney, C. R., Buehler, P. W. & Gulati, A. Purification and chemical modifications of hemoglobin in developing hemoglobin based oxygen carriers. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 40, 153–169 (2000).

Sehgal, L. R. et al. Preparation and in vitro characteristics of polymerized pyridoxylated hemoglobin. Transfusion 23, 158–162 (1983).

Hughes, G. S. Jr et al. Hematologic effects of a novel hemoglobin-based oxygen carrier in normal male and female subjects. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 126, 441–451 (1995).

Conover, C. et al. The effects of hemodilution with polyethylene glycol conjugated bovine hemoglobin (PEG–Hb) in a conscious porcine model. J. Investig. Med. 44, 238–246 (1996).

Iwasaka, K. & Iwashita, Y. Preparation and evaluation of hemoglobin–polyethylene glycol (pyridoxylated polyethylene glycol hemoglobin) as an oxygen-carrying resuscitation fluid. Artif. Organs 10, 411–416 (1986).

Moore, G. L. et al. Molecular weight determinations of O-raffinose-polymerized human hemoglobin. Biomater. Artif. Cells Immobilized Biotechnol. 20, 293–296 (1992).

Chatterjee, R. et al. Isolation and characterization of a new hemoglobin derivative crosslinked between the α chains (lysine 99α1 → lysine 99α2). J. Biol. Chem. 261, 9929–9937 (1986). A landmark paper that provided a full description and characterization of diaspirin crosslinked Hb, and which stimulated numerous research projects on this and other chemically modified Hbs.

Highsmith, F. A. et al. An improved process for the production of sterile modified haemoglobin solutions. Biologicals 25, 257–268 (1997).

Hoffman, S. et al. Expression of fully functional tetrameric human hemoglobin in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 87, 8521–8525 (1990). The first report on the expression of fully functional Hb after introduction of the human genes into Escherichia coli . Somatogen subsequently designed a novel derivative in which the two α subunits were genetically fused.

Resta, T. C. et al. Rate of NO scavenging alters effects of recombinant hemoglobin solutions on pulmonary vasoactivity. J. Appl. Physiol. 93, 1327–1336 (2002).

Vandegriff, K. D. et al. MP4, a new non-vasoactive polyethylene glycol–hemoglobin conjugate. Transfusion 43, 509–516 (2003).

Nagababu, E., Somasundaran, R., Rifkind, J. M., Jia, Y. & Alayash, A. I. Site-specific crosslinking of human and bovine hemoglobins differentially alters oxygen binding and redox side reaction producing rhombic heme and heme degradation. Biochemistry 41, 7407–7415 (2002).

Sakai, H. et al. Microvascular responses to hemodilution with Hb vesicles as red cell substitutes: influnce of O2 affinity. Am. J. Physiol. 276, H553–H562 (1999).

Niiler, E. Setbacks for blood substitutes companies. Nature Biotechnol. 20, 962–963 (2002).

Sloan, E. P. et al. Diaspirin cross-linked hemoglobin (DCLHb) in the treatment of severe traumatic hemorrhagic shock: a randomized controlled efficacy trial. JAMA 282, 1857–1864 (1999).

Sloan, E. P. et al. Post hoc mortality analysis of the efficacy trail of diaspirin cross-linked hemoglobin in the treatment of severe traumatic hemorrhagic shock. J. Trauma 52, 887–895 (2002). Mortality analysis in a traumatic haemorrhagic shock study, which involved both clinical case reviews and mortality prediction models. The models demonstrated excess unpredicted deaths in the DCLHb subgroup.

Schubert, A. et al. Diaspirin crosslinked hemoglobin reduces blood transfusion in noncardiac surgery: a multicenter, randomized controlled double-blinded trial. Anesth. Analg. 97, 323–332 (2003).

Alayash, A. I. Hemoglobin-based blood substitutes: oxygen carriers, pressor agents, or oxidants? Nature Biotechnol. 17, 545–549 (1999).

Alayash, A. I. & Cashon, R. E. Hemoglobin and free radicals: implications for the development of a safe blood substitute. Mol. Med. Today 1, 122–127 (1995).

Winslow, R. M. Alternative oxygen therapeutics: products, status of clinical trials, and future prospects. Curr. Hematol. Rep. 2, 503–510 (2003).

Misra, H. P. & Fridovich, I. The generation of superoxide radical during the autoxidation of hemoglobin. J. Biol. Chem. 247, 6960–6962 (1972).

Giulivi, C. & Cadenas, E. Heme protein radicals: formation, fate, and biological consequences. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 24, 269–279 (1998).

Nagababu, E. & Rifkind, J. M. Heme degradation during autoxidation of oxyhemoglobin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 273, 839–845 (2000).

Nagababu, E. & Rifkind, J. M. Reaction of hydrogen peroxide with ferrylhemoglobin: superoxide production and heme degradation. Biochemistry 39, 12503–12511 (2000). This article reported investigation of the mechanism of haem degradation during the reaction of oxyHb with peroxide. It established that degradation involves reaction of an additional peroxide molecule with ferrylHb to produce metHb and superoxide radical.

Motterlini, R. et al. Oxidative-stress response in vascular endothelial cells exposed to acellular hemoglobin solutions. Am. J. Physiol. 269, H648–H655 (1995).

Everse, J. & Hsia, N. The toxicities of native and modified hemoglobins. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 22, 1075–1099 (1997).

Svistunenko, D. A., Patel, R. P., Voloshchenko, S. V. & Wilson, M. T. The globin-based free radical of ferryl hemoglobin is detected in normal human blood. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 7114–7121 (1997).

Balla, J. et al. Endothelial-cell heme uptake from heme proteins: induction of sensitization and desensitization to oxidant damage. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 90, 9285–9289 (1993).

McLeod, L. L. & Alayash, A. I. Detection of a ferrylhemoglobin intermediate in an endothelial cell model after hypoxia-reoxygenation. Am. J. Physiol. 277, H92–H99 (1999).

D'Agnillo, F. D. & Alayash, A. I. Interactions of hemoglobin with hydrogen peroxide alters thiol levels and course of endothelial cell death. Am. J. Physiol. 274, H1880–H1889 (2000).

D'Agnillo, F. & Alayash, A. I. Redox cycling of diaspirin cross-linked hemoglobin induces G2/M arrest and apoptosis in cultured endothelial cells. Blood 98, 3315–3323 (2001). This study systematically presented evidence to show that cell-free Hb under mild oxidative stress can cause endothelial cells to undergo growth arrest and death.

Baldwin, A. L. Modified hemoglobins produce venular interendothelial gaps and albumin leakage in the rat mesentery. Am. J. Physiol. 277, H650–H659 (1999). The rat mesenteric preparation was used to quantify the effects of chemically modified Hbs on microvascular leakage to radiolabelled albumin to investigate changes in the integrity of interendothelial cell junctions and the endothelium cytoskeleton.

Baldwin, A. L., Wiley, E. B. & Alayash, A. I. Comparison of effects of two hemoglobin-based oxygen carriers on intestinal integrity and microvascular leakage. Am. J. Physiol. 283, H1292–H1301 (2003).

Reeder, B. J. et al. Toxicity of myoglobin and haemoglobin: oxidative stress in patients with rhabdomyolysis and subarachnoid haemorrhage. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 30, 745–748 (2002).

Jeney, V. et al. Pro-oxidant and cytotoxic effects of circulating heme. Blood 100, 879–887 (2002).

Yachie, A. et al. Oxidative stress causes enhanced endothelial cell injury in human heme oxygenase-1 deficiency. J. Clin. Invest. 103, 129–135 (1999).

Faivre, B., Menu, P., Labrude, P. & Vigneron, C. Hemoglobin autooxidation/oxidation mechanisms and methemoglobin prevention or reduction processes in the bloodstream. Literature review and outline of autooxidation reaction. Artif Cells Blood Substit Immobil Biotechnol 26, 17–26 (1998).

Editorial. NO, the molecule of the year. Science 254, 1853 (1992).

Moncada, S. Nitric oxide gas: mediator, modulator, and pathophysiologic entity. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 120, 187–191 (1992).

Liao, J. C. et al. Intravascular flow decreases erythrocyte consumption of nitric oxide. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 96, 8757–8761 (1999). Using isolated microvessels as a bioassay, this study showed that intravascular flow can affect NO consumption by RBCs but not by free Hb in the lumen, owing to the formation of an RBC-free zone near the vessel wall.

Joshi, M. S. et al. Nitric oxide is consumed, rather than conserved, by reaction with oxyhemoglobin under physiological conditions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 10341–10346 (2002).

Rohlfs, R. J. et al. Arterial blood pressure responses to cell-free hemoglobin solutions and the reaction with nitric oxide. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 12128–12134 (1998). Changes in mean arterial pressure were monitored in rats following 50% isovolemic exchange transfusion with several chemically modified Hbs. According to this article, blood pressure changes cannot be the result of a reaction between NO and Hb, and are due to alternative mechanisms.

Gould, S. A. & Moss, G. S. Clinical development of human polymerized hemoglobin as blood substitute. World J. Surg. 20, 1200–1207 (1996).

Abassi, Z. et al. Effects of polymerization on the hypertensive action of diaspirin cross-linked hemoglobin in rats. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 129, 603–610 (1997). A test of the hypothesis that polymerization of Hb can reduce or eliminate blood pressure in an animal model. The haemodynamic profiles of diaspirin crossliked Hb and its polymerized form were basically similar in rats under partial exchange transfusion.

Doyle, M. P., Apostol, I. & Kerwin, B. A. Glutaraldehyde modification of recombinant hemoglobin alters its hemodynamic properties. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 2582–2591 (1999).

Palaparthy, R., Saini, B. K. & Gulati, A. Modulation of diaspirin cross-linked hemoglobin induced systemic and reginal hemodynamic response by ethanol in rats. Life Sci. 68, 1383–1394 (2001).

Doherty, D. H. et al. Rate of reaction of nitric oxide determines the hypertensive effect of cell-free hemoglobin. Nature Biotechnol. 16, 672–676 (1998). The authors constructed and tested a set of recombinant Hbs that vary in rates of reaction with NO. The data indicated that the reaction of Hb with NO is the fundamental cause of hypertension.

Reiter, C. D. et al. Cell-free hemoglobin limits nitric oxide bioavailability in sickle cell disease. Nature Med. 8, 1383–1389 (2002).

Tsai, A. G., Vandegriff, K. D., Intaglietta, M. & Winslow, R. M. Targeted O2 delivery by low-P50 hemoglobin (MP4): a new basis for O2 therapeutics. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 285, H1411–H1419 (2003).

Winslow, R. M. Current status of blood substitute research; towards a new paradigm. J. Int. Med. 253, 508–517 (2003).

Bunn, H. F. & Forget, B. G. Hemoglobin: Molecular, Genetic and Clinical Aspects (W. B. Saunders, Philadelphia, 1986).

Joshi, M. S., Ponthier, J. L. & Lancaster, J. R. Cellular antioxidant and pro-oxidant actions of nitric oxide. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 27, 1357–1366 (1999).

Yeh, L. H. & Alayash, A. I. Redox side reactions of hemoglobin and cell signaling mechanisms. J. Int. Med. 253, 518–526 (2003).

Alayash, A. I., Patel, R. P. & Cashon, R. E. Redox reactions of hemoglobin and myoglobin: biological and toxicological implications. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 3, 313–327 (2001).

Tang, X. D. et al. Haem can bind to and inhibit mammalian calcium-dependent SIo1 BK channels. Nature 425, 531–535 (2003).

Cashon, R. E. & Alayash, A. I. Reactions of human hemoglobin A0 and two cross-linked derivatives with hydrogen peroxide: differential behavior of the ferryl intermediate. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 316, 461–469 (1995).

Alayash, A. I. Effects of intra- and intermolecular crosslinking on free radical reactivity of bovine hemoglobins. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 18, 295–301 (1995).

Osawa, Y., Derbyshire, J. F., Meyer, C. A. & Alayash, A. I. Differential susceptibilities of the prosthetic heme of hemoglobin-based red cell substitutes: implications in the design of safer agents. Biochem. Pharmacol. 46, 2299–2305 (1993).

Dou, Y., Maillett, D. H., Eich, R. F. & Olson, J. S. Myoglobin as a model system for designing heme protein based blood substitutes. Biophys. Chem. 10, 127–148 (2002).

Alayash, A. I., Ryan, B. A., Eich, R. F., Olson, J. S. & Cashon, R. E. Reactions of sperm whale myoglobin with hydrogen peroxide. Effects of distal pocket mutations on the formation and stability of the ferryl intermediate. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 2029–2037 (1999).

Tsai, C. H. et al. Novel recombinant hemoglobin, rHb (βN108) with low oxygen affinity, high cooperativity and stability against autoxidation. Biochemistry 14, 13719–13729 (2000).

D'Agnillo, F. & Chang, T. M. S. Polyhemoglobin–superoxide dismutase–catalase as a blood substitute with antioxidant properties. Nature Biotechnol. 16, 667–671 (1998).

Powanda, D. D. & Chang, T. M. Cross–linked polyhemoglobin–superoxide dismutase–catalase supplies oxygen without causing blood–brain barrier disruption or brain edema in a rat model of transient global brain ischemia–reperfusion.. Artif. Cells Blood Substit. Immobil. Biotechnol. 30, 23–37 (2002).

Krishna, M. C. & Sumuni, A. Nitroxides as antioxidants. Methods Enz. 234, 580–589 (1994).

Hoffman, A., Goldstein, S., Samuni, A., Borman, J. B. & Schwalb, H. Effect of nitric oxide and nitroxide SOD-mimic on the recovery of isolated rat heart following ischemia and reperfusion. Biochem. Pharmacol. 66, 1279–1286 (2003).

Saetzler, R. K. et al. Polynitroxylated hemoglobin-based oxygen carrier: inhibition of free radical-induced microcirculatory dysfunction. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 27, 1–6 (1999).

Allegra, T. L. et al. Reactions of melatonin with hemoglobin-derived oxyferryl radicals and inhibition of the hemoglobin denaturation in red blood cells. J. Pineal. Res. 31, 114–119 (2001).

Reagan, R. F. & Panter, S. S. Neurotoxicity of hemoglobin in cortical cell culture. Neurosci. Lett. 153, 219–222 (1993).

Simoni, J. et al. A novel hemoglobin adenosine-glutathione based blood substitute: evaluation of its effects on human blood ex vivo. ASAIO J. 46, 679–692 (2000).

Talarico, T., Swank, A. & Privalle, C. Autoxidation of pyridoxalated hemoglobin polyoxyetheylene conjugate. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 250, 354–358 (1998).

Murakami, K. et al. Pyridoxalated haemoglobin polyoxyetheylene, a nitric oxide scavenger, decreases dose-limiting hypotension associated with interleukin-2 (IL-2) therapy. Clin. Science 105, 629–635 (2003).

Weis, W. Ascorbic acid and biological systems. Ascorbic acid electron transport. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 258, 190–200 (1975).

Galaris, D., Eddy, L., Arduini, A., Cadenas, E. & Hochstein, P. Mechanisms of reoxygenation injury in myocardial infarction: implications of a myoglobin redox cycle. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 160, 1162–1168 (1989).

Wu, F. et al. Ferryl myoglobin formation induced by acute magnesium deficiency in perfused rat heart causes cardiac failure. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1225, 158–164 (1994).

D'Agnillo, F. & Alayash, A. I. A role for the myoglobin redox cycle in the induction of endothelial cell apoptosis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 33, 1153–1164 (2002).

Baldwin, A. L., Wiley, E. B., Summers, A. G. & Alayash, A. I. Sodium selenite reduces hemoglobin-induced venular leakage in the rat mesentery. Am. J. Physiol. 284, H81–H91 (2003).

Baldwin, A. L., Wiley, E. B. & Alayash, A. I. Differential effects of sodium selenium in reducing tissue damage caused by three hemoglobin-based oxygen carriers. J. Appl. Physiol. 2003 Oct 10; [epub ahead of print]

Riess, J. G. Oxygen carriers ('blood substitutes') — raison d'etre, chemistry, and some physiology. Chem. Rev. 101, 2797–2894 (2001). A comprehensive review of blood substitutes that includes chemistry, characterization and manufacturing of perfluorochemicals and Hb-based blood substitutes. It also covered some physiological and clinical aspects of the development of these products.

Clark, L. C. & Gollan, F. Survival of mammals breathing organic liquids equilibrated with oxygen at atmospheric pressure. Science 152, 1755–1756 (1966).

Savitsky, J. P., Doczi, J., Black, J. & Arnold, J. D. A clinical safety trial of stroma-free hemoglobin. Clin. Pharmacol. Therap. 23, 73–80 (1978). The first published clinical trial in which unmodified stroma-free Hb was tested in human volunteers.

Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research. Points to consider in the safety evaluation of hemoglobin-based oxygen carriers. Transfusion 31, 369–371 (1991).

Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research. Points to consider on efficacy evaluation of hemoglobin- and perfluorocarbon-based oxygen carriers. Transfusion 34, 712–713 (1994).

Acknowledgements

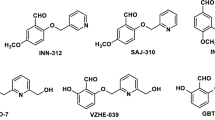

J. S. Olson of Rice University, USA, kindly provided Figures 1 and 4. J. M. Rifkind of the National Institutes of Health, USA, kindly provided the concept for Figure 2.

Disclaimer

The opinions and assertions contained herein are the scientific views of the author and are not to be construed as policy of the United States Food and Drug Administration.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing financial interests.

Related links

Related links

FURTHER INFORMATION

Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research

Encyclopedia of Life Sciences

Glossary

- BLOOD SUBSTITUTE

-

The terms 'blood substitute' and 'artificial blood' are misnomers, as the compounds discussed in this article provide oxygen transport and volume replacement, but do not perform other functions of blood, such as facilitating immune responses, coagulation and transport of nutrients. These agents are more appropriately termed 'haemoglobin-based oxygen carriers' (HBOCs) or 'oxygen therapeutics'.

- ELECTRON PARAMAGNETIC RESONANCE

-

Resonant absorption of microwave radiation by paramagnetic ions or molecules, with at least one unpaired electron spin, and in the presence of static magnetic field.

- ENDOTHELIN

-

A vasoactive peptide produced by endothelium.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Alayash, A. Oxygen therapeutics: can we tame haemoglobin?. Nat Rev Drug Discov 3, 152–159 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd1307

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd1307

This article is cited by

-

Selective Attachment of Polyethylene Glycol to Hemerythrin for Potential Use in Blood Substitutes

The Protein Journal (2023)

-

Macrophages Protect Endometriotic Cells Against Oxidative Damage Through a Cross-Talk Mechanism

Reproductive Sciences (2022)

-

Resuscitation with macromolecular superoxide dismutase/catalase mimetic polynitroxylated PEGylated hemoglobin offers neuroprotection in guinea pigs after traumatic brain injury combined with hemorrhage shock

BMC Neuroscience (2020)

-

Plant based production of myoglobin - a novel source of the muscle heme-protein

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Oxygen dissociation from ferrous oxygenated human hemoglobin:haptoglobin complexes confirms that in the R-state α and β chains are functionally heterogeneous

Scientific Reports (2019)