Key Points

-

Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) is one of the few molecular markers routinely used for detection, risk stratification and monitoring of a common cancer.

-

PSA is specific to the prostate but not to prostate cancer: benign prostate diseases often cause increases in serum PSA and most men with increased PSA do not have prostate cancer.

-

PSA strongly discriminates different cancer stages: it is higher in men with localized disease than in cancer-free controls, is associated with stage and grade in localized disease and is higher in patients with metastatic compared with localized disease.

-

Men with a higher PSA at the time of initial therapy have increased risk of recurrence.

-

PSA is a sensitive indicator of recurrence after radical prostatectomy, but far less sensitive as an indicator of recurrence after radiation therapy.

-

PSA before age 50 is a strong predictor of prostate cancer occurring up to 25 years later.

-

The introduction of PSA as a screening test has led to a sharp increase in the incidence of prostate cancer because there has been a shift to diagnosis at earlier stages and there is probably substantial 'overdiagnosis' — men diagnosed with prostate cancer whose cancer would never have affected their lives if they had not had a PSA test.

-

The effects of PSA screening on prostate cancer mortality are not yet clear.

Abstract

Testing for prostate-specific antigen (PSA) has profoundly affected the diagnosis and treatment of prostate cancer. PSA testing has enabled physicians to detect prostate tumours while they are still small, low-grade and localized. This very ability has, however, created controversy over whether we are now diagnosing and treating insignificant cancers. PSA testing has also transformed the monitoring of treatment response and detection of disease recurrence. Much current research is directed at establishing the most appropriate uses of PSA testing and at developing methods to improve on the conventional PSA test.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Lilja, H. A kallikrein-like serine protease in prostatic fluid cleaves the predominant seminal vesicle protein. J . Clin. Invest. 76, 1899–1903 (1985).

Herrala, A. M., Porvari, K. S., Kyllonen, A. P. & Vihko, P. T. Comparison of human prostate specific glandular kallikrein 2 and prostate specific antigen gene expression in prostate with gene amplification and overexpression of prostate specific glandular kallikrein 2 in tumor tissue. Cancer 92, 2975–2984 (2001).

Lintula, S., Stenman, J., Bjartell, A., Nordling, S. & Stenman, U. H. Relative concentrations of hK2/PSA mRNA in benign and malignant prostatic tissue. Prostate 63, 324–329 (2005).

Ahlgren, G., Rannevik, G. & Lilja, H. Impaired secretory function of the prostate in men with oligo-asthenozoospermia. J. Androl. 16, 491–498 (1995).

Lilja, H., Oldbring, J., Rannevik, G. & Laurell, C. B. Seminal vesicle-secreted proteins and their reactions during gelation and liquefaction of human semen. J. Clin. Invest. 80, 281–285 (1987).

Lundwall, A., Clauss, A. & Olsson, A. Y. Evolution of kallikrein-related peptidases in mammals and identification of a genetic locus encoding potential regulatory inhibitors. Biol. Chem. 387, 243–249 (2006).

Olsson, A. Y., Lilja, H. & Lundwall, A. Taxon-specific evolution of glandular kallikrein genes and identification of a progenitor of prostate-specific antigen. Genomics 84, 147–156 (2004).

Savblom, C. et al. Blood levels of free-PSA but not complex-PSA significantly correlates to prostate release of PSA in semen in young men, while blood levels of complex-PSA, but not free-PSA increase with age. Prostate 65, 66–72 (2005).

Niemela, P., Lovgren, J., Karp, M., Lilja, H. & Pettersson, K. Sensitive and specific enzymatic assay for the determination of precursor forms of prostate-specific antigen after an activation step. Clin. Chem. 48, 1257–1264 (2002).

Piironen, T. et al. Measurement of circulating forms of prostate-specific antigen in whole blood immediately after venipuncture: implications for point-of-care testing. Clin. Chem. 47, 703–711 (2001).

Christensson, A., Laurell, C. B. & Lilja, H. Enzymatic activity of prostate-specific antigen and its reactions with extracellular serine proteinase inhibitors. Eur. J. Biochem. 194, 755–763 (1990).

Qiu, S. D. et al. In situ hybridization of prostate-specific antigen mRNA in human prostate. J. Urol. 144, 1550–1556 (1990).

Ung, J. O., Richie, J. P., Chen, M. H., Renshaw, A. A. & D'Amico, A. V. Evolution of the presentation and pathologic and biochemical outcomes after radical prostatectomy for patients with clinically localized prostate cancer diagnosed during the PSA era. Urology 60, 458–463 (2002).

Aus, G. et al. Individualized screening interval for prostate cancer based on prostate-specific antigen level: results of a prospective, randomized, population-based study. Arch. Intern. Med. 165, 1857–1861 (2005).

Gann, P. H., Hennekens, C. H. & Stampfer, M. J. A prospective evaluation of plasma prostate-specific antigen for detection of prostatic cancer. Jama 273, 289–294 (1995).

Stenman, U. H. et al. Serum concentrations of prostate specific antigen and its complex with α1-antichymotrypsin before diagnosis of prostate cancer. Lancet 344, 1594–1598 (1994). This classic paper was the first to suggest that PSA is powerful as a long-term predictor of prostate cancer. The study is, however, limited by the small number of cancer cases analysed and by the degradation of PSA in archived serum samples.

Thompson, I. M. et al. Prevalence of prostate cancer among men with a prostate-specific antigen level ≤ 4.0 ng per milliliter. N. Engl. J. Med. 350, 2239–2246 (2004). Unique study showing cancer incidence among men of ages 62–91 with PSA levels of 0–4 ng/ml, based on end-of-study biopsies of the men randomized to the control arm of the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial.

Ulmert, D. et al. Long-term prediction of prostate cancer: PSA velocity is predictive but does not improve the predictive accuracy of a single PSA measurement 15 years or more before cancer diagnosis in a large, representative, unscreened population. J. Clin. Oncol. 26, 835–841 (2008).

Andriole, G. L. et al. Prostate cancer screening in the prostate, lung, colorectal and ovarian (PLCO) cancer screening trial: findings from the initial screening round of a randomized trial. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 97, 433–438 (2005).

Crawford, E. D. et al. Serum prostate-specific antigen and digital rectal examination for early detection of prostate cancer in a national community-based program. The Prostate Cancer Education Council. Urology 47, 863–869 (1996).

Hugosson, J., Aus, G., Lilja, H., Lodding, P. & Pihl, C. G. Results of a randomized, population-based study of biennial screening using serum prostate-specific antigen measurement to detect prostate carcinoma. Cancer 100, 1397–1405 (2004).

Thompson, I. M. et al. Effect of finasteride on the sensitivity of PSA for detecting prostate cancer. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 98, 1128–1133 (2006).

Thompson, I. M. et al. Operating characteristics of prostate-specific antigen in men with an initial PSA level of 3.0 ng/ml or lower. JAMA 294, 66–70 (2005).

Thompson, I. M. et al. Assessing prostate cancer risk: results from the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 98, 529–34 (2006). Describes an online calculator that estimates a man's risk of prostate cancer from his PSA level, age, race, family history of prostate cancer, results of digital rectal examination and any prior biopsy results.

Marks, L. S., Andriole, G. L., Fitzpatrick, J. M., Schulman, C. C. & Roehrborn, C. G. The interpretation of serum prostate specific antigen in men receiving 5α-reductase inhibitors: a review and clinical recommendations. J. Urol. 176, 868–874 (2006).

D'Amico, A. V. & Roehrborn, C. G. Effect of 1 mg/day finasteride on concentrations of serum prostate-specific antigen in men with androgenic alopecia: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 8, 21–25 (2007).

Thompson, I. M. et al. Prediction of prostate cancer for patients receiving finasteride: results from the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 25, 3076–3081 (2007).

Verhamme, K. M. et al. Incidence and prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms suggestive of benign prostatic hyperplasia in primary care — the Triumph project. Eur. Urol. 42, 323–328 (2002).

Morgan, T. O. et al. Age-specific reference ranges for prostate-specific antigen in black men. N. Engl. J. Med. 335, 304–310 (1996).

Oesterling, J. E. et al. Free, complexed and total serum prostate specific antigen: the establishment of appropriate reference ranges for their concentrations and ratios. J. Urol. 154, 1090–1095 (1995).

Borer, J. G., Sherman, J., Solomon, M. C., Plawker, M. W. & Macchia, R. J. Age specific prostate specific antigen reference ranges: population specific. J. Urol. 159, 444–448 (1998).

Fang, J. et al. Low levels of prostate-specific antigen predict long-term risk of prostate cancer: results from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Urology 58, 411–416 (2001).

Loeb, S. et al. Baseline prostate-specific antigen compared with median prostate-specific antigen for age group as predictor of prostate cancer risk in men younger than 60 years old. Urology 67, 316–320 (2006).

Lilja, H. et al. Long-term prediction of prostate cancer up to 25 years before diagnosis of prostate cancer using prostate kallikreins measured at age 44 to 50 years. J. Clin. Oncol. 25, 431–436 (2007).

Ulmert, D. et al. Prostate-specific antigen at or before age 50 as a predictor of prostate cancer of unquestionable significance up to 25 years later: a case-control study. BMC Med. 6, 6 (2008). This paper shows that a single PSA test taken at or before age 50 is a strong predictor of advanced prostate cancer diagnosed up to 25 years later, with advanced cancer defined as cancer that is locally advanced or metastatic at the time of diagnosis.

Vickers, A. J. et al. The predictive value of prostate cancer biomarkers depends on age and time to diagnosis: towards a biologically-based screening strategy. Int. J. Cancer 121, 2212–2217 (2007).

Grossklaus, D. J. et al. The free/total prostate-specific antigen ratio (%fPSA) is the best predictor of tumor involvement in the radical prostatectomy specimen among men with an elevated PSA. Urol. Oncol. 7, 195–198 (2002).

Stamey, T. A. et al. Prostate-specific antigen as a serum marker for adenocarcinoma of the prostate. N. Engl. J. Med. 317, 909–916 (1987). This classic paper demonstrated that PSA is elevated in blood of patients with prostate cancer or BPH, and that it is associated with clinical stage and tumor volume.

Pinsky, P. F. et al. Prostate-specific antigen velocity and prostate cancer gleason grade and stage. Cancer 109, 1689–1695 (2007).

Hoedemaeker, R. F. et al. Pathologic features of prostate cancer found at population-based screening with a four-year interval. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 93, 1153–1158 (2001).

Sakr, W. A. et al. Age and racial distribution of prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia. Eur. Urol. 30, 138–144 (1996).

Jemal, A. et al. Cancer statistics, 2007. CA Cancer J. Clin. 57, 43–66 (2007).

Telesca, D. Etzioni, R. & Gulati, R. Estimating lead time and overdiagnosis associated with PSA screening from prostate cancer incidence trends. Biometrics 14 May 2007 (doi: 10.1111/j.1541–0420.2007.00825.x). This study provides estimates of lead time and rates of overdiagnosis of prostate cancer resulting from PSA testing, based on trends in the incidence of prostate cancer.

Postma, R. et al. Cancer detection and cancer characteristics in the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) — Section Rotterdam. A comparison of two rounds of screening. Eur. Urol. 52, 89–97 (2007).

Bill-Axelson, A. et al. Radical prostatectomy versus watchful waiting in early prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 352, 1977–1984 (2005).

Aus, G., Bergdahl, S., Lodding, P., Lilja, H. & Hugosson, J. Prostate cancer screening decreases the absolute risk of being diagnosed with advanced prostate cancer--results from a prospective, population-based randomized controlled trial. Eur. Urol. 51, 659–664 (2007). Early results from a randomized trial of PSA screening, showing that screening reduced both frequency and absolute number of prostate cancer cases that were metastatic at diagnosis.

Karazanashvili, G. & Abrahamsson, P. A. Prostate specific antigen and human glandular kallikrein 2 in early detection of prostate cancer. J. Urol. 169, 445–57 (2003).

Ohori, M., Dunn, J. K. & Scardino, P. T. Is prostate-specific antigen density more useful than prostate-specific antigen levels in the diagnosis of prostate cancer? Urology 46, 666–671 (1995).

Lilja, H. et al. Prostate-specific antigen in serum occurs predominantly in complex with α1-antichymotrypsin. Clin. Chem. 37, 1618–1625 (1991).

Stenman, U. H. et al. A complex between prostate-specific antigen and α 1-antichymotrypsin is the major form of prostate-specific antigen in serum of patients with prostatic cancer: assay of the complex improves clinical sensitivity for cancer. Cancer Res. 51, 222–226 (1991).

Christensson, A. et al. Serum prostate specific antigen complexed to α 1-antichymotrypsin as an indicator of prostate cancer. J. Urol. 150, 100–105 (1993).

Catalona, W. J. et al. Use of the percentage of free prostate-specific antigen to enhance differentiation of prostate cancer from benign prostatic disease: a prospective multicenter clinical trial. JAMA 279, 1542–1547 (1998). This report, based on a large cohort, was the first to propose a cut-off for the percentage of free PSA as criterion for prostate biopsy.

Ulmert, D. et al. Reproducibility and accuracy of measurements of free and total prostate-specific antigen in serum vs plasma after long-term storage at −20 degrees C. Clin. Chem. 52, 235–239 (2006).

Morote, J. et al. The percentage of free prostatic-specific antigen is also useful in men with normal digital rectal examination and serum prostatic-specific antigen between 10.1 and 20 ng/ml. Eur. Urol. 42, 333–337 (2002).

Roddam, A. W. et al. Use of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) isoforms for the detection of prostate cancer in men with a PSA level of 2–10 ng/ml: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Urol. 48, 386–399; discussion 398–399 (2005). This thorough meta-analysis demonstrates the improvement in diagnostic performance gained by measuring the percentage of free PSA in addition to tPSA.

Stephan, C., Lein, M., Jung, K., Schnorr, D. & Loening, S. A. The influence of prostate volume on the ratio of free to total prostate specific antigen in serum of patients with prostate carcinoma and benign prostate hyperplasia. Cancer 79, 104–109 (1997).

Peter, J., Unverzagt, C., Krogh, T. N., Vorm, O. & Hoesel, W. Identification of precursor forms of free prostate-specific antigen in serum of prostate cancer patients by immunosorption and mass spectrometry. Cancer Res. 61, 957–962 (2001).

Catalona, W. J. et al. Serum pro prostate specific antigen improves cancer detection compared to free and complexed prostate specific antigen in men with prostate specific antigen 2 to 4 ng/ml. J. Urol. 170, 2181–2185 (2003).

Mikolajczyk, S. D. et al. Proenzyme forms of prostate-specific antigen in serum improve the detection of prostate cancer. Clin. Chem. 50, 1017–1025 (2004).

Mikolajczyk, S. D. et al. A precursor form of prostate-specific antigen is more highly elevated in prostate cancer compared with benign transition zone prostate tissue. Cancer Res. 60, 756–759 (2000).

Nurmikko, P., Pettersson, K., Piironen, T., Hugosson, J. & Lilja, H. Discrimination of prostate cancer from benign disease by plasma measurement of intact, free prostate-specific antigen lacking an internal cleavage site at Lys145-Lys146. Clin. Chem. 47, 1415–1423 (2001).

Steuber, T. et al. Association of free-prostate specific antigen subfractions and human glandular kallikrein 2 with volume of benign and malignant prostatic tissue. Prostate 63, 13–18 (2005).

Slawin, K. M., Shariat, S. & Canto, E. BPSA: A novel serum marker for benign prostatic hyperplasia. Rev. Urol. 7 (Suppl. 8), 52–56 (2005).

Carter, H. B. et al. Longitudinal evaluation of prostate-specific antigen levels in men with and without prostate disease. JAMA 267, 2215–2220 (1992).

D'Amico, A. V., Chen, M. H., Roehl, K. A. & Catalona, W. J. Preoperative PSA velocity and the risk of death from prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy. N. Engl. J. Med. 351, 125–135 (2004).

D'Amico, A. V., Renshaw, A. A., Sussman, B. & Chen, M. H. Pretreatment PSA velocity and risk of death from prostate cancer following external beam radiation therapy. JAMA 294, 440–447 (2005).

D'Amico, A. V. et al. Predictors of mortality after prostate-specific antigen failure. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 65, 656–660 (2006).

Leibovici, D. et al. Prostate cancer progression in the presence of undetectable or low serum prostate-specific antigen level. Cancer 109, 198–204 (2007).

Nishio, R., Furuya, Y., Nagakawa, O. & Fuse, H. Metastatic prostate cancer with normal level of serum prostate-specific antigen. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 35, 189–192 (2003).

Stephenson, A. J. et al. Defining biochemical recurrence of prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy: a proposal for a standardized definition. J. Clin. Oncol. 24, 3973–3978 (2006).

Amling, C. L., Bergstralh, E. J., Blute, M. L., Slezak, J. M. & Zincke, H. Defining prostate specific antigen progression after radical prostatectomy: what is the most appropriate cut point? J. Urol. 165, 1146–1151 (2001).

Vaisanen, V., Peltola, M. T., Lilja, H., Nurmi, M. & Pettersson, K. Intact free prostate-specific antigen and free and total human glandular kallikrein 2. Elimination of assay interference by enzymatic digestion of antibodies to F(ab′)2 fragments. Anal. Chem. 78, 7809–7815 (2006).

Diamandis, E. P. & Yu, H. Nonprostatic sources of prostate-specific antigen. Urol. Clin. North Am. 24, 275–282 (1997).

Kupelian, P. et al. Improved biochemical relapse-free survival with increased external radiation doses in patients with localized prostate cancer: the combined experience of nine institutions in patients treated in 1994 and 1995. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 61, 415–419 (2005). This study showed that PSA level after radiation therapy reflects the radiation dose, which is in turn associated with relapse-free survival.

Miller, N., Smolkin, M. E., Bissonette, E. & Theodorescu, D. Undetectable prostate specific antigen at 6–12 months: a new marker for early success in hormonally treated patients after prostate brachytherapy. Cancer 103, 2499–2506 (2005).

Hanlon, A. L., Moore, D. F. & Hanks, G. E. Modeling postradiation prostate specific antigen level kinetics: predictors of rising postnadir slope suggest cure in men who remain biochemically free of prostate carcinoma. Cancer 83, 130–134 (1998).

Ray, M. E. et al. PSA nadir predicts biochemical and distant failures after external beam radiotherapy for prostate cancer: a multi-institutional analysis. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 64, 1140–1150 (2006).

Critz, F. A. et al. Post-treatment PSA ≤0.2 ng/mL defines disease freedom after radiotherapy for prostate cancer using modern techniques. Urology 54, 968–971 (1999).

Cavanagh, W., Blasko, J. C., Grimm, P. D. & Sylvester, J. E. Transient elevation of serum prostate-specific antigen following 125I/103Pd brachytherapy for localized prostate cancer. Semin. Urol. Oncol. 18, 160–165 (2000).

Reed, D., Wallner, K., Merrick, G., Buskirk, S. & True, L. Clinical correlates to PSA spikes and positive repeat biopsies after prostate brachytherapy. Urology 62, 683–688 (2003).

Crook, J. et al. PSA kinetics and PSA bounce following permanent seed prostate brachytherapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 69, 426–433 (2007).

Patel, C. et al. PSA bounce predicts early success in patients with permanent iodine-125 prostate implant. Urology 63, 110–113 (2004).

Toledano, A. et al. PSA bounce after permanent implant prostate brachytherapy may mimic a biochemical failure: a study of 295 patients with a minimum 3-year followup. Brachytherapy 5, 122–126 (2006).

Hanlon, A. L., Pinover, W. H., Horwitz, E. M. & Hanks, G. E. Patterns and fate of PSA bouncing following 3D-CRT. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 50, 845–849 (2001).

Horwitz, E. M. et al. Biochemical and clinical significance of the posttreatment prostate-specific antigen bounce for prostate cancer patients treated with external beam radiation therapy alone: a multiinstitutional pooled analysis. Cancer 107, 1496–1502 (2006).

Rosser, C. J. et al. Is patient age a factor in the occurrence of prostate-specific antigen bounce phenomenon after external beam radiotherapy for prostate cancer? Urology 66, 327–331 (2005).

Thames, H. et al. Comparison of alternative biochemical failure definitions based on clinical outcome in 4839 prostate cancer patients treated by external beam radiotherapy between 1986 and 1995. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 57, 929–943 (2003).

Roach, M. 3rd et al. Defining biochemical failure following radiotherapy with or without hormonal therapy in men with clinically localized prostate cancer: recommendations of the RTOG-ASTRO Phoenix Consensus Conference. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 65, 965–974 (2006).

Horwitz, E. M. et al. Definitions of biochemical failure that best predict clinical failure in patients with prostate cancer treated with external beam radiation alone: a multi-institutional pooled analysis. J. Urol. 173, 797–802 (2005). A demonstration that the Phoenix definition of biochemical recurrence after radiation therapy (a rise of 2 ng/ml above PSA nadir) is a better predictor of clinical failure and of metastases than is the ASTRO definition.

Kuban, D. A. et al. Comparison of biochemical failure definitions for permanent prostate brachytherapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 65, 1487–1493 (2006).

Stamey, T. A., Kabalin, J. N., Ferrari, M. & Yang, N. Prostate specific antigen in the diagnosis and treatment of adenocarcinoma of the prostate. IV. Anti-androgen treated patients. J. Urol. 141, 1088–1090 (1989).

Benaim, E. A., Pace, C. M., Lam, P. M. & Roehrborn, C. G. Nadir prostate-specific antigen as a predictor of progression to androgen-independent prostate cancer. Urology 59, 73–78 (2002).

Kwak, C., Jeong, S. J., Park, M. S., Lee, E. & Lee, S. E. Prognostic significance of the nadir prostate specific antigen level after hormone therapy for prostate cancer. J. Urol. 168, 995–1000 (2002). This study demonstrated that PSA nadir after initiation of hormonal therapy is an important predictor of both time to hormone-refractory disease and survival.

Miller, J. I., Ahmann, F. R., Drach, G. W., Emerson, S. S. & Bottaccini, M. R. The clinical usefulness of serum prostate specific antigen after hormonal therapy of metastatic prostate cancer. J. Urol. 147, 956–961 (1992).

Ryan, C. J. et al. Persistent prostate-specific antigen expression after neoadjuvant androgen depletion: an early predictor of relapse or incomplete androgen suppression. Urology 68, 834–839 (2006).

Scher, H. I. & Sawyers, C. L. Biology of progressive, castration-resistant prostate cancer: directed therapies targeting the androgen-receptor signaling axis. J. Clin. Oncol. 23, 8253–8261 (2005).

Arai, Y., Yoshiki, T. & Yoshida, O. Prognostic significance of prostate specific antigen in endocrine treatment for prostatic cancer. J. Urol. 144, 1415–1419 (1990).

Furuya, Y. et al. Prognostic significance of changes in prostate-specific antigen in patients with metastasis prostate cancer after endocrine treatment. Int. Urol. Nephrol 32, 659–663 (2001).

Matzkin, H., Eber, P., Todd, B., van der Zwaag, R. & Soloway, M. S. Prognostic significance of changes in prostate-specific markers after endocrine treatment of stage D2 prostatic cancer. Cancer 70, 2302–2309 (1992).

Zanetti, G. et al. Prognostic significance of prostate-specific antigen in endocrine treatment for prostatic carcinoma. Eur. Urol. 21 (Suppl. 1), 96–98 (1992).

Furuya, Y., Nagakawa, O. & Fuse, H. Prognostic significance of changes in short-term prostate volume and serum prostate-specific antigen after androgen withdrawal in men with metastatic prostate cancer. Urol. Int. 70, 195–199 (2003).

Morote, J., Trilla, E., Esquena, S., Abascal, J. M. & Reventos, J. Nadir prostate-specific antigen best predicts the progression to androgen-independent prostate cancer. Int. J. Cancer 108, 877–881 (2004).

Armstrong, A. J. et al. Prostate-specific antigen and pain surrogacy analysis in metastatic hormone-refractory prostate cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 25, 3965–3970 (2007).

Bjork, T. et al. Rapid exponential elimination of free prostate-specific antigen contrasts the slow, capacity-limited elimination of PSA complexed to α1-antichymotrypsin from serum. Urology 51, 57–62 (1998).

Becker, C., Piironen, T., Pettersson, K., Hugosson, J. & Lilja, H. Testing in serum for human glandular kallikrein 2, and free and total prostate specific antigen in biannual screening for prostate cancer. J. Urol. 170, 1169–1174 (2003).

Raaijmakers, R. et al. hK2 and free PSA, a prognostic combination in predicting minimal prostate cancer in screen-detected men within the PSA Range 4–10 ng/ml. Eur. Urol. 52, 1358–1364 (2007).

Steuber, T. et al. Comparison of free and total forms of serum human kallikrein 2 and prostate-specific antigen for prediction of locally advanced and recurrent prostate cancer. Clin. Chem. 53, 233–240 (2007).

Denmeade, S. R. et al. Prostate-specific antigen-activated thapsigargin prodrug as targeted therapy for prostate cancer. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 95, 990–1000 (2003).

Fowler, J. E., Bigler, S. A., Kilambi, N. K. & Land, S. A. Relationships between prostate-specific antigen and prostate volume in black and white men with benign prostate biopsies. Urology 53, 1175–1178 (1999).

Moul, J. W. et al. Prostate-specific antigen values at the time of prostate cancer diagnosis in African-American men. JAMA 274, 1277–1281 (1995).

Catalona, W. J. et al. Percentage of free PSA in black versus white men for detection and staging of prostate cancer: a prospective multicenter clinical trial. Urology 55, 372–376 (2000).

Stanford, J. L . et al. Prostate Cancer Trends 1973–1995 (SEER Program; National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, 1999).

Mettlin, C. J., Murphy, G. P., Ho, R. & Menck, H. R. The National Cancer Data Base report on longitudinal observations on prostate cancer. Cancer 77, 2162–2166 (1996).

Finne, P. et al. Use of the complex between prostate specific antigen and α 1-protease inhibitor for screening prostate cancer. J. Urol. 164, 1956–1960 (2000).

Lilja, H. et al. Significance and metabolism of complexed and noncomplexed prostate specific antigen forms, and human glandular kallikrein 2 in clinically localized prostate cancer before and after radical prostatectomy. J. Urol. 162, 2029–2034; discussion 2034–2035 (1999).

Zhang, W. M. et al. Characterization and immunological determination of the complex between prostate-specific antigen and α2-macroglobulin. Clin. Chem. 44, 2471–2479 (1998).

Lane, J. A. et al. Detection of prostate cancer in unselected young men: prospective cohort nested within a randomised controlled trial. BMJ 335, 1139 (2007).

Donovan, J. et al. Prostate Testing for Cancer and Treatment (ProtecT) feasibility study. Health Technol. Assess 7, 1–88 (2003).

Shibata, A. & Whittemore, A. S. Re: Prostate cancer incidence and mortality in the United States and the United Kingdom. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 93, 1109–1110 (2001).

Oliver, S. E., Gunnell, D. & Donovan, J. L. Comparison of trends in prostate-cancer mortality in England and Wales and the USA. Lancet 355, 1788–1789 (2000).

Roehl, K. A. et al. Survival results in patients with screen-detected prostate cancer versus physician-referred patients treated with radical prostatectomy: early results. Urol. Oncol. 24, 465–471 (2006).

Oberaigner, W. et al. Reduction of prostate cancer mortality in Tyrol, Austria, after introduction of prostate-specific antigen testing. Am. J. Epidemiol. 164, 376–384 (2006).

Shaw, P. A. et al. An ecologic study of prostate-specific antigen screening and prostate cancer mortality in nine geographic areas of the United States. Am. J. Epidemiol. 160, 1059–1069 (2004).

Kopec, J. A. et al. Screening with prostate specific antigen and metastatic prostate cancer risk: a population based case-control study. J. Urol. 174, 495–499; discussion 499 (2005).

Concato, J. et al. The effectiveness of screening for prostate cancer: a nested case-control study. Arch. Intern. Med. 166, 38–43 (2006).

Weinmann, S. et al. Screening by prostate-specific antigen and digital rectal examination in relation to prostate cancer mortality: a case-control study. Epidemiology 16, 367–376 (2005).

Lu-Yao, G. et al. Natural experiment examining impact of aggressive screening and treatment on prostate cancer mortality in two fixed cohorts from Seattle area and Connecticut. BMJ 325, 740 (2002).

Ciatto, S. et al. Prostate cancer specific mortality in the Florence screening pilot study cohort 1992–1993. Eur. J. Cancer 42, 1858–1862 (2006).

Coldman, A. J., Phillips, N. & Pickles, T. A. Trends in prostate cancer incidence and mortality: an analysis of mortality change by screening intensity. CMAJ 168, 31–35 (2003).

Labrie, F. et al. Screening decreases prostate cancer mortality: 11-year follow-up of the 1988 Quebec prospective randomized controlled trial. Prostate 59, 311–318 (2004).

Sandblom, G., Varenhorst, E., Lofman, O., Rosell, J. & Carlsson, P. Clinical consequences of screening for prostate cancer: 15 years follow-up of a randomised controlled trial in Sweden. Eur. Urol. 46, 717–723; discussion 724 (2004).

van der Cruijsen-Koeter, I. W. et al. Comparison of screen detected and clinically diagnosed prostate cancer in the European randomized study of screening for prostate cancer, section Rotterdam. J. Urol. 174, 121–125 (2005).

Acknowledgements

We thank A. M. Cronin of Memorial Sloan–Kettering Cancer Center for compiling data on the distribution of PSA levels. We also thank J. Novak of Helix Editing for assistance with writing the manuscript. She was paid for her work by Memorial Sloan–Kettering Cancer Center.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Dr Hans Lilja is patent holder for free PSA and hK2 blood assays.

Related links

Related links

DATABASES

National cancer institute

National cancer institute Drug Dictionary

FURTHER INFORMATION

Glossary

- Stage migration

-

The decrease over time in the proportion of men with prostate cancer who are found to have advanced stage disease at diagnosis, commonly attributed to the introduction of PSA testing, which identifies prostate cancer at an earlier stage in the disease process.

- Specificity

-

The number of people who test negative for a disease and who are disease-free, divided by the total number of people who are disease-free and who were tested. For a PSA test this is the proportion of men with no prostate cancer who have a low level of PSA.

- Sensitivity

-

The number of people who test positive for a disease and who have the disease, divided by the total number of people who have disease and who were tested. For a PSA test this is the proportion of men with prostate cancer who have increased PSA.

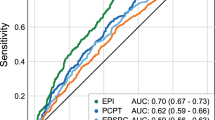

- AUC

-

Area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve. This value gives the probability that, in a pair of patients, one of whom had the event and the other of whom did not, the patient who had the event was given the higher risk by the predictive model.

- External beam therapy

-

The use of radiation from a high-energy source external to the patient as a treatment for cancer.

- Brachytherapy

-

Implantation of radioactive pellets, approximately the size of a grain of rice, into the tissue being treated for cancer.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lilja, H., Ulmert, D. & Vickers, A. Prostate-specific antigen and prostate cancer: prediction, detection and monitoring. Nat Rev Cancer 8, 268–278 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc2351

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc2351

This article is cited by

-

Interdigitated impedimetric-based Maackia amurensis lectin biosensor for prostate cancer biomarker

Microchimica Acta (2024)

-

Suppression of bone metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer cell growth by a suicide gene delivered by JC polyomavirus-like particles

Gene Therapy (2023)

-

A big data-based prediction model for prostate cancer incidence in Japanese men

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Predictive value of kallikrein forms and β-microseminoprotein in blood from patients with evidence of detectable levels of PSA after radical prostatectomy

World Journal of Urology (2023)

-

Electrochemical ELASA: improving early cancer detection and monitoring

Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry (2023)