Abstract

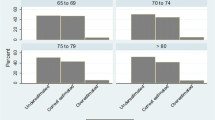

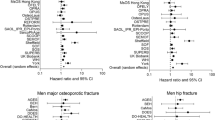

Introduction and objective Misreporting fractures in questionnaires is known. However, the effect of misreporting on the association of fractures with subsequent health outcomes has not been examined. Methods Data from a fracture registry (FR) developed from an extensive review of radiographic and medical records were related to self-report of fracture for 2,255 participants from the AGES Reykjavik Study. This data was used to determine false negative and false positive rates of self-reported fractures, correlates of misreporting, and the potential effect of the misreporting on estimates of health outcomes following fractures. Results In women, the false positive rate decreased with age as the false negative rate increased with no clear trend with age in men. Kappa values for agreement between FR and self-report were generally higher in women than men with the best agreement for forearm fracture (men 0.64 and women 0.82) and the least for rib (men 0.28 and women 0.25). Impaired cognition was a major factor associated with discordant answers between FR and self-report, OR 1.7 (95% CI: 1.3–2.1) (P < 0.0001). We estimated the effect of misreporting on health after fracture by comparison of the association of the self-report of fracture and fracture from the FR, adjusting for those factors associated with discordance. The weighted attenuation factor measured by mobility and muscle strength was 11% (95% CI: 0–24%) when adjusted for age and sex but reduced to 6% (95% CI: −10–22%) when adjusted for cognitive impairment. Conclusion Studies of hip fractures should include an independent ascertainment of fracture but for other fractures this study supports the use of self-report.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Newell SA, Girgis A, Sanson-Fisher RW, et al. The accuracy of self-reported health behaviors and risk factors relating to cancer and cardiovascular disease in the general population: a critical review. Am J Prev Med 1999;17(3):211–29.

Simpson CF, Boyd CM, Carlson MC, et al. Agreement between self-report of disease diagnoses and medical record validation in disabled older women: factors that modify agreement. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004;52(1):123–7.

Nevitt MC, Cummings SR, Browner WS, et al. The accuracy of self-report of fractures in elderly women: evidence from a prospective study. Am J Epidemiol 1992;135(5):490–9.

Hundrup YA, Hoidrup S, Obel EB, et al. The validity of self-reported fractures among Danish female nurses: comparison with fractures registered in the Danish National Hospital Register. Scand J Public Health 2004;32(2):136–43.

Honkanen K, Honkanen R, Heikkinen L, et al. Validity of self-reports of fractures in perimenopausal women. Am J Epidemiol 1999;150(5):511–6.

Akesson K, Gardsell P, Sernbo I, et al. Earlier wrist fracture: a confounding factor in distal forearm bone screening. Osteoporos Int 1992;2(4):201–4.

Beard CM, Melton LJ III, Cedel SL, Richelson LS, Riggs BL. Ascertainment of risk factors for osteoporosis: comparison of interview data with medical record review. J Bone Miner Res 1990;5(7):691–9.

Colditz GA, Martin P, Stampfer MJ, Willett et al. Validation of questionnaire information on risk factors and disease outcomes in a prospective cohort study of women. Am J Epidemiol 1986;123(5):894–900.

Paganini-Hill A, Chao A. Accuracy of recall of hip fracture, heart attack, and cancer: a comparison of postal survey data and medical records. Am J Epidemiol 1993;138(2):101–6.

Chen Z, Kooperberg C, Pettinger MB, Bassford T, Cauley JA, LaCroix AZ, et al. Validity of self-report for fractures among a multiethnic cohort of postmenopausal women: results from the Women’s Health Initiative observational study and clinical trials. Menopause 2004;11(3):264–74.

Bergmann MM, Byers T, Freedman DS, Mokdad A. Validity of self-reported diagnoses leading to hospitalization: a comparison of self-reports with hospital records in a prospective study of American adults. Am J Epidemiol 1998;147(10):969–77.

Ismail AA, O’Neill TW, Cockerill W, Finn JD, Cannata JB, Hoszowski K, et al. Validity of self-report of fractures: results from a prospective study in men and women across Europe. EPOS Study Group. European Prospective Osteoporosis Study Group. Osteoporos Int 2000;11(3):248–54.

Ivers RQ, Cumming RG, Mitchell P, Peduto AJ. The accuracy of self-reported fractures in older people. J Clin Epidemiol 2002;55(5):452–7.

Jonsson B, Gardsell P, Johnell O, Redlund-Johnell I, Sernbo I. Remembering fractures: fracture registration and proband recall in southern Sweden. J Epidemiol Community Health 1994;48(5):489–90.

Harris TB, Launer LJ, Eiriksdottir G, Kjartansson O, Jonsson PV, Sigurdsson G, et al. Age, Gene/Environment Susceptibility-Reykjavik Study: multidisciplinary applied phenomics. Am J Epidemiol 2007;165(9):1076–87.

Jonsdottir LS, Sigfusson N, Gudnason V, Sigvaldason H, Thorgeirsson G. Do lipids, blood pressure, diabetes, and smoking confer equal risk of myocardial infarction in women as in men? The Reykjavik Study. J Cardiovasc Risk 2002;9(2):67–76.

Blank JB, Cawthon PM, Carrion-Petersen ML, Harper L, Johnson JP, Mitson E, et al. Overview of recruitment for the osteoporotic fractures in men study (MrOS). Contemp Clin Trials 2005;26(5):557–68.

Orwoll E, Blank JB, Barrett-Connor E, Cauley J, Cummings S, Ensrud K, et al. Design and baseline characteristics of the osteoporotic fractures in men (MrOS) study–a large observational study of the determinants of fracture in older men. Contemp Clin Trials 2005;26(5):569–85.

Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. The timed “Up & Go”: a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 1991;39(2):142–8.

Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, Glynn RJ, Berkman LF, Blazer DG, et al. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol 1994;49(2):M85–94.

Ostir GV, Markides KS, Black SA, Goodwin JS. Lower body functioning as a predictor of subsequent disability among older Mexican Americans. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 1998;53(6):M491–5.

Tiainen K, Sipila S, Alen M, Heikkinen E, Kaprio J, Koskenvuo M, et al. Heritability of maximal isometric muscle strength in older female twins. J Appl Physiol 2004;96(1):173–80.

EuroQol G. EuroQol—a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. The EuroQol Group. Health Policy 1990;16(3):199–208.

Altman DG, Bland JM. Diagnostic tests. 1: Sensitivity and specificity. BMJ 1994;308(6943):1552.

Altman DG. Practical Statistics for Medical Research. London: Chapman & Hall; 1995.

Altman DG, Bland JM. Diagnostic tests 2: Predictive values. BMJ 1994;309(6947):102.

Lloyd SS, Rissing JP. Physician and coding errors in patient records. Jama 1985;254(10):1330–6.

Lorenzoni L, Da Cas R, Aparo UL. The quality of abstracting medical information from the medical record: the impact of training programmes. Int J Qual Health Care 1999;11(3):209–13.

Joakimsen RM, Fonnebo V, Sogaard AJ, Tollan A, Stormer J, Magnus JH. The Tromso study: registration of fractures, how good are self-reports, a computerized radiographic register and a discharge register? Osteoporos Int 2001;12(12):1001–5.

Delmas PD, van de Langerijt L, Watts NB, Eastell R, Genant H, Grauer A, et al. Underdiagnosis of vertebral fractures is a worldwide problem: the IMPACT study. J Bone Miner Res 2005;20(4):557–63.

Braithwaite RS, Col NF, Wong JB. Estimating hip fracture morbidity, mortality and costs. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51(3):364–70.

Empana JP, Dargent-Molina P, Breart G. Effect of hip fracture on mortality in elderly women: the EPIDOS prospective study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004;52(5):685–90.

Holmes JD, House AO. Psychiatric illness in hip fracture. Age Ageing 2000;29(6):537–46.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by NIH contract N01-AG-12100 and in part by the NIA Intramural Research Program., the Icelandic Parliament and the Icelandic Heart Association. Conflict of interest: none declared.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

10654_2007_9163_MOESM1_ESM.pdf

Comparison of the fracture registry and self-report, association of hip, vertebra, forearm and all fracture to the activity of daily living and health related quality of life. Adjusted for age and sex. Superimposed is a weighted least squares regression line and a 45 degree reference line. The scales shows the odds ratio of poor performance. (PDF 88 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Siggeirsdottir, K., Aspelund, T., Sigurdsson, G. et al. Inaccuracy in self-report of fractures may underestimate association with health outcomes when compared with medical record based fracture registry. Eur J Epidemiol 22, 631–639 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-007-9163-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-007-9163-9