Abstract

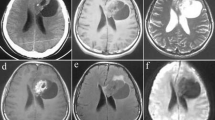

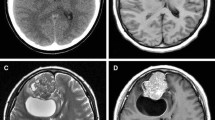

Craniopharyngiomas (CP) are benign epithelial tumors of the sellar region and can be clinicopathologically distinguished into adamantinomatous (adaCP) and papillary (papCP) variants. Both subtypes are classified according to the World Health Organization grade I, but their irregular digitate brain infiltration makes any complete surgical resection difficult to obtain. Herein, we characterized the cellular interface between the tumor and the surrounding brain tissue in 48 CP (41 adaCP and seven papCP) compared to non-neuroepithelial tumors, i.e., 12 cavernous hemangiomas, 10 meningiomas, and 14 metastases using antibodies directed against glial fibrillary acid protein (GFAP), vimentin, nestin, microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2) splice variants, and tenascin-C. We identified a specific cell population characterized by the coexpression of nestin, MAP2, and GFAP within the invasion niche of the adamantinomatous subtype. This was especially prominent along the finger-like protrusions. A similar population of presumably astroglial precursors was not visible in other lesions under study, which characterize them as distinct histopathological feature of adaCP. Furthermore, the outer tumor cell layer of adaCP showed a distinct expression of MAP2, a novel finding helpful in the differential diagnosis of epithelial tumors in the sellar region. Our data support the hypothesis that adaCP, unlike other non-neuroepithelial tumors of the central nervous system, create a tumor-specific cellular environment at the tumor–brain junction. Whether this facilitates the characteristic infiltrative growth pattern or is the consequence of an activated Wnt signaling pathway, detectable in 90% of these tumors, will need further consideration.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Bunin GR, Surawicz TS, Witman PA et al (1998) The descriptive epidemiology of craniopharyngioma. J Neurosurg 89:547–551

Kuratsu J, Ushio Y (1996) Epidemiological study of primary intracranial tumors in childhood. A population-based survey in Kumamoto Prefecture, Japan. Pediatr Neurosurg 25:240–246, discussion 247

Adamson TE, Wiestler OD, Kleihues P et al (1990) Correlation of clinical and pathological features in surgically treated craniopharyngiomas. J Neurosurg 73:12–17

Sekine S, Shibata T, Kokubu A et al (2002) Craniopharyngiomas of adamantinomatous type harbor beta-catenin gene mutations. Am J Pathol 161:1997–2001

Kato K, Nakatani Y, Kanno H et al (2004) Possible linkage between specific histological structures and aberrant reactivation of the Wnt pathway in adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma. J Pathol 203:814–821

Buslei R, Nolde M, Hofmann B et al (2005) Common mutations of beta-catenin in adamantinomatous craniopharyngiomas but not in other tumours originating from the sellar region. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 109:589–597

Hofmann BM, Kreutzer J, Saeger W et al (2006) Nuclear beta-catenin accumulation as reliable marker for the differentiation between cystic craniopharyngiomas and rathke cleft cysts: a clinico-pathologic approach. Am J Surg Pathol 30:1595–1603

Kendall-Taylor P, Jonsson PJ, Abs R et al (2005) The clinical, metabolic and endocrine features and the quality of life in adults with childhood-onset craniopharyngioma compared with adult-onset craniopharyngioma. Eur J Endocrinol 152:557–567

Karavitaki N, Cudlip S, Adams CB et al (2006) Craniopharyngiomas. Endocr Rev 27:371–397

Gleeson H, Amin R, Maghnie M (2008) ‘Do no harm’: management of craniopharyngioma. Eur J Endocrinol 159(Suppl 1):S95–S99

Muller HL (2008) Childhood craniopharyngioma. Recent advances in diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Horm Res 69:193–202

Fahlbusch R, Hofmann BM (2008) Surgical management of giant craniopharyngiomas. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 150:1213–1226

Kawamata T, Kubo O, Hori T (2005) Histological findings at the boundary of craniopharyngiomas. Brain Tumor Pathol 22:75–78

Fahlbusch R, Honegger J, Paulus W et al (1999) Surgical treatment of craniopharyngiomas: experience with 168 patients. J Neurosurg 90:237–250

Muller HL, Albanese A, Calaminus G et al (2006) Consensus and perspectives on treatment strategies in childhood craniopharyngioma: results of a meeting of the Craniopharyngioma Study Group (SIOP), Genova, 2004. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 19(Suppl 1):453–454

Garre ML, Cama A (2007) Craniopharyngioma: modern concepts in pathogenesis and treatment. Curr Opin Pediatr 19:471–479

Puget S, Garnett M, Wray A et al (2007) Pediatric craniopharyngiomas: classification and treatment according to the degree of hypothalamic involvement. J Neurosurg 106:3–12

Lendahl U, Zimmerman LB, McKay RD (1990) CNS stem cells express a new class of intermediate filament protein. Cell 60:585–595

Wei LC, Shi M, Chen LW et al (2002) Nestin-containing cells express glial fibrillary acidic protein in the proliferative regions of central nervous system of postnatal developing and adult mice. Brain Res Dev Brain Res 139:9–17

Messam CA, Hou J, Berman JW et al (2002) Analysis of the temporal expression of nestin in human fetal brain derived neuronal and glial progenitor cells. Brain Res Dev Brain Res 134:87–92

Sugawara K, Kurihara H, Negishi M et al (2002) Nestin as a marker for proliferative endothelium in gliomas. Lab Invest 82:345–351

Erickson HP, Bourdon MA (1989) Tenascin: an extracellular matrix protein prominent in specialized embryonic tissues and tumors. Annu Rev Cell Biol 5:71–92

Gu H, Wang S, Messam CA et al (2002) Distribution of nestin immunoreactivity in the normal adult human forebrain. Brain Res 943:174–180

Joester A, Faissner A (2001) The structure and function of tenascins in the nervous system. Matrix Biol 20:13–22

Scheffler B, Faissner A, Beck H et al (1997) Hippocampal loss of tenascin boundaries in Ammon's horn sclerosis. Glia 19:35–46

Reardon DA, Zalutsky MR, Bigner DD (2007) Antitenascin-C monoclonal antibody radioimmunotherapy for malignant glioma patients. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 7:675–687

Liu HY, Nur EKA, Schachner M et al (2005) Neurite guidance by the FnC repeat of human tenascin-C: neurite attraction vs. neurite retention. Eur J Neurosci 22:1863–1872

Riederer B, Matus A (1985) Differential expression of distinct microtubule-associated proteins during brain development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 82:6006–6009

Riederer BM, Barakat-Walter I (1992) Differential distribution of two microtubule-associated proteins, MAP2 and MAP5, during chick dorsal root ganglion development in situ and in culture. Brain Res Dev Brain Res 68:111–123

Ferralli J, Doll T, Matus A (1994) Sequence analysis of MAP2 function in living cells. J Cell Sci 107(Pt 11):3115–3125

Kindler S, Schulz B, Goedert M et al (1990) Molecular structure of microtubule-associated protein 2b and 2c from rat brain. J Biol Chem 265:19679–19684

Kalcheva N, Albala J, O'Guin K et al (1995) Genomic structure of human microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP-2) and characterization of additional MAP-2 isoforms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 92:10894–10898

Shafit-Zagardo B, Davies P, Rockwood J et al (2000) Novel microtubule-associated protein-2 isoform is expressed early in human oligodendrocyte maturation. Glia 29:233–245

Blumcke I, Muller S, Buslei R et al (2004) Microtubule-associated protein-2 immunoreactivity: a useful tool in the differential diagnosis of low-grade neuroepithelial tumors. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 108:89–96

Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD et al (2007) The 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol 114:97–109

Blumcke I, Becker AJ, Normann S et al (2001) Distinct expression pattern of microtubule-associated protein-2 in human oligodendrogliomas and glial precursor cells. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 60:984–993

Yasuda Y, Fujita S (2003) Distribution of MAP1A, MAP1B, and MAP2A&B during layer formation in the optic tectum of developing chick embryos. Cell Tissue Res 314:315–324

Buslei R, Holsken A, Hofmann B et al (2007) Nuclear beta-catenin accumulation associates with epithelial morphogenesis in craniopharyngiomas. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 113:585–590

Lefranc F, Mijatovic T, Decaestecker C et al (2005) Monitoring the expression profiles of integrins and adhesion/growth-regulatory galectins in adamantinomatous craniopharyngiomas: their ability to regulate tumor adhesiveness to urrounding tissue and their contribution to prognosis. Neurosurgery 56:763–776

Rotondo F, Oniya K, Kovacs K et al (2005) MAP-2 expression in the human adenohypophysis and in pituitary adenomas. An immunohistochemical study. Pituitary 8:75–79

Weiner HL, Wisoff JH, Rosenberg ME et al (1994) Craniopharyngiomas: a clinicopathological analysis of factors predictive of recurrence and functional outcome. Neurosurgery 35:1001–1010, discussion 1010–1011

Crotty TB, Scheithauer BW, Young WF Jr (1995) Papillary craniopharyngioma: a clinicopathological study of 48 cases. J Neurosurg 83:206–214

Hirano A, Wate R (2007) Diagnostic clues and more from photographs. Neuropathology 27:1–9

Liszczak T, Richardson EP Jr, Phillips JP et al (1978) Morphological, biochemical, ultrastructural, tissue culture and clinical observations of typical and aggressive craniopharyngiomas. Acta Neuropathol 43:191–203

Karavitaki N, Brufani C, Warner JT et al (2005) Craniopharyngiomas in children and adults: systematic analysis of 121 cases with long-term follow-up. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 62:397–409

Rutka JT, Apodaca G, Stern R et al (1988) The extracellular matrix of the central and peripheral nervous systems: structure and function. J Neurosurg 69:155–170

Giese A, Rief MD, Loo MA et al (1994) Determinants of human astrocytoma migration. Cancer Res 54:3897–3904

Shafit-Zagardo B, Kress Y, Zhao ML et al (1999) A novel microtubule-associated protein-2 expressed in oligodendrocytes in multiple sclerosis lesions. J Neurochem 73:2531–2537

Cosenza MA, Zhao ML, Shankar SL et al (2002) Up-regulation of MAP2e-expressing oligodendrocytes in the white matter of patients with HIV-1 encephalitis. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 28:480–488

Toma JG, Akhavan M, Fernandes KJ et al (2001) Isolation of multipotent adult stem cells from the dermis of mammalian skin. Nat Cell Biol 3:778–784

Kim SY, Lee SH, Kim BM et al (2004) Activation of nestin-positive duct stem (NPDS) cells in pancreas upon neogenic motivation and possible cytodifferentiation into insulin-secreting cells from NPDS cells. Dev Dyn 230:1–11

Krum JM, Rosenstein JM (1999) Transient coexpression of nestin, GFAP, and vascular endothelial growth factor in mature reactive astroglia following neural grafting or brain wounds. Exp Neurol 160:348–360

Leins A, Riva P, Lindstedt R et al (2003) Expression of tenascin-C in various human brain tumors and its relevance for survival in patients with astrocytoma. Cancer 98:2430–2439

Sarkar S, Nuttall RK, Liu S et al (2006) Tenascin-C stimulates glioma cell invasion through matrix metalloproteinase-12. Cancer Res 66:11771–11780

Beiter K, Hiendlmeyer E, Brabletz T et al (2005) beta-Catenin regulates the expression of tenascin-C in human colorectal tumors. Oncogene 24:8200–8204

Faissner A, Steindler D (1995) Boundaries and inhibitory molecules in developing neural tissues. Glia 13:233–254

O'Brien TF, Faissner A, Schachner M et al (1992) Afferent-boundary interactions in the developing neostriatal mosaic. Brain Res Dev Brain Res 65:259–267

Freeman RS, Barone MC (2005) Targeting hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) as a therapeutic strategy for CNS disorders. Curr Drug Targets CNS Neurol Disord 4:85–92

Holsken A, Kreutzer J, Hofmann BM et al (2009) Target gene activation of the Wnt signaling pathway in nuclear beta-catenin accumulating cells of adamantinomatous craniopharyngiomas. Brain Pathol 19(3):357–364

Acknowledgements

We kindly thank T. Jungbauer, K. Kalus, B. Rings, S. Sterner, and especially V. Schmidt for the expert technical support. We thank Dr. R. Coras and Dipl. Biochem. K. Kobow for the helpful discussions. This work was supported by the ELAN Foundation from the University Hospital of Erlangen, School of Medicine.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Burghaus, S., Hölsken, A., Buchfelder, M. et al. A tumor-specific cellular environment at the brain invasion border of adamantinomatous craniopharyngiomas. Virchows Arch 456, 287–300 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-009-0873-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-009-0873-0