Abstract

The suboptimal performance of bone mineral density as the sole predictor of fracture risk and treatment decision making has led to the development of risk prediction algorithms that estimate fracture probability using multiple risk factors for fracture, such as demographic and physical characteristics, personal and family history, other health conditions, and medication use. We review theoretical aspects for developing and validating risk assessment tools, and illustrate how these principles apply to the best studied fracture probability tools: the World Health Organization FRAX®, the Garvan Fracture Risk Calculator, and the QResearch Database’s QFractureScores. Model development should follow a systematic and rigorous methodology around variable selection, model fit evaluation, performance evaluation, and internal and external validation. Consideration must always be given to how risk prediction tools are integrated into clinical practice guidelines to support better clinical decision making and improved patient outcomes. Accurate fracture risk assessment can guide clinicians and individuals in understanding the risk of having an osteoporosis-related fracture and inform their decision making to mitigate these risks.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Stone KL, Seeley DG, Lui LY et al (2003) BMD at multiple sites and risk of fracture of multiple types: long-term results from the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures. J Bone Miner Res 18:1947–1954

Wiktorowicz ME, Goeree R, Papaioannou A et al (2001) Economic implications of hip fracture: health service use, institutional care and cost in Canada. Osteoporos Int 12:271–278

Papaioannou A, Adachi JD, Parkinson W et al (2001) Lengthy hospitalization associated with vertebral fractures despite control for comorbid conditions. Osteoporos Int 12:870–874

Center JR, Nguyen TV, Schneider D et al (1999) Mortality after all major types of osteoporotic fracture in men and women: an observational study. Lancet 353:878–882

Johnell O, Kanis JA, Oden A et al (2004) Mortality after osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int 15:38–42

Ioannidis G, Papaioannou A, Hopman WM et al (2009) Relation between fractures and mortality: results from the Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study. CMAJ 181:265–271

Adachi JD, Ioannidis G, Berger C et al (2001) The influence of osteoporotic fractures on health-related quality of life in community-dwelling men and women across Canada. Osteoporos Int 12:903–908

Hallberg I, Rosenqvist AM, Kartous L et al (2004) Health-related quality of life after osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int 15:834–841

Johnell O, Kanis JA (2006) An estimate of the worldwide prevalence and disability associated with osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int 17:1726–1733

Melton LJ III (2003) Epidemiology worldwide. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 32:1–13

Kanis JA, Melton LJ III, Christiansen C et al (1994) The diagnosis of osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res 9:1137–1141

Looker AC, Wahner HW, Dunn WL et al (1998) Updated data on proximal femur bone mineral levels of US adults. Osteoporos Int 8:468–489

Kanis JA, McCloskey EV, Johansson H et al (2008) A reference standard for the description of osteoporosis. Bone 42:467–475

Johnell O, Kanis JA, Oden A et al (2005) Predictive value of BMD for hip and other fractures. J Bone Miner Res 20:1185–1194

Marshall D, Johnell O, Wedel H (1996) Meta-analysis of how well measures of bone mineral density predict occurrence of osteoporotic fractures. BMJ 312:1254–1259

Cranney A, Jamal SA, Tsang JF et al (2007) Low bone mineral density and fracture burden in postmenopausal women. CMAJ 177:575–580

Moons KG, Kengne AP, Woodward M et al (2012) Risk prediction models: I. Development, internal validation, and assessing the incremental value of a new (bio)marker. Heart 98:683–690

Moons KG, Kengne AP, Grobbee DE et al (2012) Risk prediction models: II. External validation, model updating, and impact assessment. Heart 98:691–698

Lloyd-Jones DM (2010) Cardiovascular risk prediction: basic concepts, current status, and future directions. Circulation 121:1768–1777

Nguyen TV, Eisman JA (2013) Genetic profiling and individualized assessment of fracture risk. Nat Rev Endocrinol 9:153–161

Janssens AC, van Duijn CM (2009) Genome-based prediction of common diseases: methodological considerations for future research. Genome Med 1:20

Callas PW, Pastides H, Hosmer DW (1998) Empirical comparisons of proportional hazards, Poisson, and logistic regression modeling of occupational cohort data. Am J Ind Med 33:33–47

Datta S, DePadilla LM (2006) Feature selection and machine learning with mass spectrometry data for distinguishing cancer and non-cancer samples. Stat Meth 3:79–92

Abu-Hanna A, de Keizer N (2003) Integrating classification trees with local logistic regression in Intensive Care prognosis. Artif Intell Med 29:5–23

Peduzzi P, Concato J, Kemper E et al (1996) A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol 49:1373–1379

Steyerberg EW, Eijkemans MJ, Habbema JD (1999) Stepwise selection in small data sets: a simulation study of bias in logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol 52:935–942

Li W, Kornak J, Harris TB et al. (2009) Hip fracture risk estimation based on principal component analysis of QCT atlas: a preliminary study. Proc. SPIE 7262, Medical Imaging 2009: Biomedical Applications in Molecular, Structural, and Functional Imaging 7262:doi:10.1117/12.811743

Moons KG, Donders AR, Steyerberg EW et al (2004) Penalized maximum likelihood estimation to directly adjust diagnostic and prognostic prediction models for overoptimism: a clinical example. J Clin Epidemiol 57:1262–1270

Steyerberg EW, Eijkemans MJ, Harrell FE Jr et al (2000) Prognostic modelling with logistic regression analysis: a comparison of selection and estimation methods in small data sets. Stat Med 19:1059–1079

Nagelkerke NJD (1991) A note on a general definition of the coefficient of determination. Biomet 78:691–692

Brier GW (1950) Verification of forecasts expressed in terms of probability. Monthly Weather Review:1–3

Blattenberger G (1985) Separating the Brier score into calibration and refinement components: a graphical exposition. Am Stat 26–32

Spiegelhalter DJ (1986) Probabilistic prediction in patient management and clinical trials. Stat Med 5:421–433

Ikeda M, Ishigaki T, Yamauchi K (2002) Relationship between Brier score and area under the binormal ROC curve. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 67:187–194

Harrell FE Jr, Lee KL, Mark DB (1996) Multivariable prognostic models: issues in developing models, evaluating assumptions and adequacy, and measuring and reducing errors. Stat Med 15:361–387

DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL (1988) Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics 44:837–845

Harrell FE Jr, Lee KL, Califf RM et al (1984) Regression modelling strategies for improved prognostic prediction. Stat Med 3:143–152

Chambless LE, Diao G (2006) Estimation of time-dependent area under the ROC curve for long-term risk prediction. Stat Med 25:3474–3486

Steyerberg EW, Vickers AJ, Cook NR et al (2010) Assessing the performance of prediction models: a framework for traditional and novel measures. Epidemiology 21:128–138

Kanis JA, Oden A, Johansson H et al (2012) Pitfalls in the external validation of FRAX. Osteoporos Int 23:423–431

Pressman AR, Lo JC, Chandra M et al (2011) Methods for assessing fracture risk prediction models: experience with FRAX in a large integrated health care delivery system. J Clin Densitom 14:407–415

Leslie WD, Lix LM (2011) Absolute fracture risk assessment using lumbar spine and femoral neck bone density measurements: derivation and validation of a hybrid system. J Bone Miner Res 26:460–467

Steyerberg EW, Harrell FE Jr, Borsboom GJ et al (2001) Internal validation of predictive models: efficiency of some procedures for logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol 54:774–781

Steyerberg EW, Bleeker SE, Moll HA et al (2003) Internal and external validation of predictive models: a simulation study of bias and precision in small samples. J Clin Epidemiol 56:441–447

Royston P, Altman DG (2013) External validation of a Cox prognostic model: principles and methods. BMC Med Res Methodol 13:33

Satagopan JM, Ben-Porat L, Berwick M et al (2004) A note on competing risks in survival data analysis. Br J Cancer 91:1229–1235

Leslie WD, Lix LM, Wu X (2013) Competing mortality and fracture risk assessment. Osteoporos Int 24:681–688

Scrucca L, Santucci A, Aversa F (2007) Competing risk analysis using R: an easy guide for clinicians. Bone Marrow Transplant 40:381–387

Allison PD (ed) (2002) Missing data. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Enders CK (ed) (2010) Applied missing data analysis. Guilford, New York

Schafer JL, Graham JW (2002) Missing data: our view of the state of the art. Psychol Methods 7:147–177

Little RJA, Rubin DB (eds) (2002) Statistical analysis with missing data. Wiley, New York

Mayer B, Muche R, Hohl K (2012) Software for the handling and imputation of missing data—an overview. J Clinic Trials 2:103–111

Gourlay ML, Powers JM, Lui LY et al (2008) Clinical performance of osteoporosis risk assessment tools in women aged 67 years and older. Osteoporos Int 19:1175–1183

Rud B, Hilden J, Hyldstrup L et al (2009) The Osteoporosis Self-Assessment Tool versus alternative tests for selecting postmenopausal women for bone mineral density assessment: a comparative systematic review of accuracy. Osteoporos Int 20:599–607

Schwartz EN, Steinberg DM (2006) Prescreening tools to determine who needs DXA. Curr Osteoporos Rep 4:148–152

Kanis JA, Oden A, Johansson H et al (2009) FRAX and its applications to clinical practice. Bone 44:734–743

Kanis JA, on behalf of the World Health Organization Scientific Group. Assessment of osteoporosis at the primary health-care level. Technical Report. Accessible at http://www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX/pdfs/WHO_Technical_Report.pdf. 2007. Published by the University of Sheffield

Kanis JA, Oden A, McCloskey EV et al (2012) A systematic review of hip fracture incidence and probability of fracture worldwide. Osteoporos Int 23:2239–2256

McCloskey E, Kanis JA (2012) FRAX updates 2012. Curr Opin Rheumatol 24:554–560

Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A et al (2000) Long-term risk of osteoporotic fracture in Malmo. Osteoporos Int 11:669–674

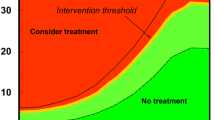

Kanis JA, Oden A, Johnell O et al (2001) The burden of osteoporotic fractures: a method for setting intervention thresholds. Osteoporos Int 12:417–427

Kanis JA, Oden A, Johnell O et al (2007) The use of clinical risk factors enhances the performance of BMD in the prediction of hip and osteoporotic fractures in men and women. Osteoporos Int 18:1033–1046

Sornay-Rendu E, Munoz F, Delmas PD et al (2010) The FRAX tool in French women: how well does it describe the real incidence of fracture in the OFELY cohort? J Bone Miner Res 25:2101–2107

Tremollieres FA, Pouilles JM, Drewniak N et al (2010) Fracture risk prediction using BMD and clinical risk factors in early postmenopausal women: sensitivity of the WHO FRAX tool. J Bone Miner Res 25:1002–1009

Leslie WD, Lix LM, Langsetmo L et al (2011) Construction of a FRAX((R)) model for the assessment of fracture probability in Canada and implications for treatment. Osteoporos Int 22:817–827

Leslie WD, Lix LM, Johansson H et al (2010) Independent clinical validation of a Canadian FRAX tool: fracture prediction and model calibration. J Bone Miner Res 25:2350–2358

Fraser LA, Langsetmo L, Berger C et al (2011) Fracture prediction and calibration of a Canadian FRAX(R) tool: a population-based report from CaMos. Osteoporos Int 22:829–837

Czerwinski E, Kanis JA, Osieleniec J et al (2011) Evaluation of FRAX to characterise fracture risk in Poland. Osteoporos Int 22:2507–2512

Tamaki J, Iki M, Kadowaki E et al (2011) Fracture risk prediction using FRAX(R): a 10-year follow-up survey of the Japanese Population-Based Osteoporosis (JPOS) Cohort Study. Osteoporos Int 22:3037–3045

Rubin KH, Abrahamsen B, Hermann AP et al (2011) Fracture risk assessed by Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX) compared with fracture risk derived from population fracture rates. Scand J Public Health 39:312–318

Premaor M, Parker RA, Cummings S et al (2013) Predictive value of FRAX for fracture in obese older women. J Bone Miner Res 28:188–195

Ettinger B, Ensrud KE, Blackwell T et al. (2013) Performance of FRAX in a cohort of community-dwelling, ambulatory older men: the Osteoporotic Fractures in Men (MrOS) study. Osteoporos Int 24:1185–1193

Byberg L, Gedeborg R, Cars T et al (2012) Prediction of fracture risk in men: a cohort study. J Bone Miner Res 27:797–807

Gonzalez-Macias J, Marin F, Vila J et al (2012) Probability of fractures predicted by FRAX(R) and observed incidence in the Spanish ECOSAP Study cohort. Bone 50:373–377

Tebe Cordomi C, Del Rio LM, Di GS et al. (2013) Validation of the FRAX predictive model for major osteoporotic fracture in a historical cohort of Spanish women. J Clin Densitom 16:231–237

Dawson-Hughes B (2008) A revised clinician's guide to the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93:2463–2465

Dawson-Hughes B, Tosteson AN, Melton LJ III et al (2008) Implications of absolute fracture risk assessment for osteoporosis practice guidelines in the USA. Osteoporos Int 19:449–458

Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A et al (2008) FRAX and the assessment of fracture probability in men and women from the UK. Osteoporos Int 19:385–397

Kanis JA, McCloskey EV, Johansson H et al (2008) Case finding for the management of osteoporosis with FRAX((R))—assessment and intervention thresholds for the UK. Osteoporos Int 19:1395–1408

Lippuner K, Johansson H, Kanis JA et al (2010) FRAX assessment of osteoporotic fracture probability in Switzerland. Osteoporos Int 21:381–389

Kanis JA, Burlet N, Cooper C et al (2008) European guidance for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int 19:399–428

Fujiwara S, Kasagi F, Masunari N et al (2003) Fracture prediction from bone mineral density in Japanese men and women. J Bone Miner Res 18:1547–1553

Neuprez A, Johansson H, Kanis JA et al (2009) [A FRAX model for the assessment of fracture probability in Belgium]. Rev Med Liege 64:612–619

Papaioannou A, Morin S, Cheung AM et al (2010) 2010 clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in Canada: summary. CMAJ 182:1864–1873

Kanis JA, Hans D, Cooper C et al (2011) Interpretation and use of FRAX in clinical practice. Osteoporos Int 22:2395–2411

Hans DB, Kanis JA, Baim S et al (2011) Joint Official Positions of the International Society for Clinical Densitometry and International Osteoporosis Foundation on FRAX((R)) Executive Summary of the 2010 Position Development Conference on Interpretation and Use of FRAX((R)) in Clinical Practice. J Clin Densitom 14:171–180

Lo JC, Pressman AR, Chandra M et al (2011) Fracture risk tool validation in an integrated healthcare delivery system. Am J Manag Care 17:188–194

Siminoski K, Leslie WD, Frame H et al (2005) Recommendations for bone mineral density reporting in Canada. Can Assoc Radiol J 56:178–188

Siminoski K, Leslie WD, Frame H et al (2007) Recommendations for bone mineral density reporting in Canada: a shift to absolute fracture risk assessment. J Clin Densitom 10:120–123

Leslie WD, Berger C, Langsetmo L et al. (2011) Construction and validation of a simplified fracture risk assessment tool for Canadian women and men: results from the CaMos and Manitoba cohorts. Osteoporos Int 22:1873–1883

Nguyen ND, Frost SA, Center JR et al (2007) Development of a nomogram for individualizing hip fracture risk in men and women. Osteoporos Int 18:1109–1117

Nguyen ND, Frost SA, Center JR et al (2008) Development of prognostic nomograms for individualizing 5-year and 10-year fracture risks. Osteoporos Int 19:1431–1444

Langsetmo L, Nguyen TV, Nguyen ND et al. (2011) Independent external validation of nomograms for predicting risk of low-trauma fracture and hip fracture. CMAJ 183:E107

Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C (2009) Predicting risk of osteoporotic fracture in men and women in England and Wales: prospective derivation and validation of QFractureScores. BMJ 339:b4229

Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C (2012) Derivation and validation of updated QFracture algorithm to predict risk of osteoporotic fracture in primary care in the United Kingdom: prospective open cohort study. BMJ 344:e3427

Collins GS, Mallett S, Altman DG (2011) Predicting risk of osteoporotic and hip fracture in the United Kingdom: prospective independent and external validation of QFractureScores. BMJ 342:d3651

Cummins NM, Poku EK, Towler MR et al (2011) Clinical risk factors for osteoporosis in Ireland and the UK: a comparison of FRAX and QFractureScores. Calcif Tissue Int 89:172–177

Black DM, Steinbuch M, Palermo L et al (2001) An assessment tool for predicting fracture risk in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int 12:519–528

Robbins J, Aragaki AK, Kooperberg C et al (2007) Factors associated with 5-year risk of hip fracture in postmenopausal women. JAMA 298:2389–2398

Henry MJ, Pasco JA, Sanders KM et al (2006) Fracture Risk (FRISK) Score: Geelong Osteoporosis Study. Radiology 241:190–196

Henry MJ, Pasco JA, Merriman EN et al (2011) Fracture risk score and absolute risk of fracture. Radiology 259:495–501

Pluijm SM, Koes B, de Laet C (2009) A simple risk score for the assessment of absolute fracture risk in general practice based on two longitudinal studies. J Bone Miner Res 24:768–774

Sambrook PN, Flahive J, Hooven FH et al (2011) Predicting fractures in an international cohort using risk factor algorithms without BMD. J Bone Miner Res 26:2770–2777

Bolland MJ, Siu AT, Mason BH et al (2011) Evaluation of the FRAX and Garvan fracture risk calculators in older women. J Bone Miner Res 26:420–427

Leslie WD, Schousboe JT (2011) A review of osteoporosis diagnosis and treatment options in new and recently updated guidelines on case finding around the world. Curr Osteoporos Rep 9:129–140

Compston J, Cooper A, Cooper C et al (2009) Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women and men from the age of 50 years in the UK. Maturitas 62:105–108

Kanis JA, McCloskey EV, Johansson H et al (2013) European guidance for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int 24:23–57

Office of the Surgeon General (US). (2004) Bone Health and Osteoporosis: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville (MD): Office of the Surgeon General (US) Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK45513/

Chen P, Krege JH, Adachi JD et al (2009) Vertebral fracture status and the World Health Organization risk factors for predicting osteoporotic fracture risk. J Bone Miner Res 24:495–502

Donaldson M, Palermo L, Schousboe JT, Ensrud K, Hochberg MC, Cummings SR (2009) FRAX and risk of vertebral fractures: The Fracture Intervention Trial (FIT). J Bone Miner Res 24:1793–1799

Ensrud KE, Lui LY, Taylor BC et al (2009) A comparison of prediction models for fractures in older women: is more better? Arch Intern Med 169:2087–2094

Leslie WD, Lix LM, Johansson H et al (2011) Spine–hip discordance and fracture risk assessment: a physician-friendly FRAX enhancement. Osteoporos Int 22:839–847

Kanis JA, McCloskey E, Johansson H et al (2012) FRAX((R)) with and without bone mineral density. Calcif Tissue Int 90:1–13

van den BT, Heymans MW, Leone SS et al (2013) Overview of data-synthesis in systematic reviews of studies on outcome prediction models. BMC Med Res Methodol 13:42

Sources of support

L.M.L. is supported by a Manitoba Research Chair.

Conflicts of interest

William Leslie: Speaker bureau: Amgen, Novartis. Research grants: Novartis, Amgen, Genzyme. Advisory boards: Novartis, Amgen. Lisa Lix: Research grant: Amgen.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Leslie, W.D., Lix, L.M. Comparison between various fracture risk assessment tools. Osteoporos Int 25, 1–21 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-013-2409-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-013-2409-3