Abstract

Urinary incontinence remains a pressing problem, particularly for women. So this study was conducted to assess risk factors for stress, urge, mixed urinary incontinence and overactive bladder (OVB). Three hundred and thirty women aged 15–49, non-pregnant, non-breastfeeding who were referred to gynecologic clinics were surveyed. A questionnaire was used to collect data. Women with no symptoms related to urinary incontinence (UI) and OVB served as the reference group. The risk of all types of UI and OVB increased with constipation. Posterior pelvic organ prolapse was associated with stress and urge incontinence. Vaginal delivery was a predictor of stress, urge and mixed incontinence. BMI and PID were predictors of OVB. Pelvic muscle strength was a predictor of stress incontinence. Vaginal length was associated with mixed incontinence. Optimal weight gain, having a healthy lifestyle, treatment of constipation and pelvic organ prolapse, and improving pelvic floor muscle strength can be suggested as preventive measures against UI and OVB. Pelvic measurement can be included in evaluation of UI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Urinary incontinence (UI) remains a pressing problem, particularly for women in both reproductive and menopausal phases of life [1]. Although various studies have revealed several possible risk factors, only a few have been rigorously studied and investigated in any age group separately in strata of different types of urinary incontinence and overactive bladder [2, 3]. Most studies have focused on risk factors for urinary incontinence in older women, and limited data are available in women of reproductive age. In addition, primary risk factors for urinary incontinence may differ in women over their life time (e.g. parity appears to be a more important risk factor in women aged under 60 than in older women) [4].

According to the principle that an effective public health intervention should have preventive measures as the main tool, effective prevention can only be achieved if there is a clear understanding of the cause and risk factors of the disease, and for UI such understanding is lacking [5].

So we conducted this study to determine related factors of stress, urge, mixed urinary incontinence and overactive bladder in women of reproductive age in Tabriz, Iran.

Method

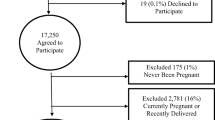

This was a cross-sectional study conducted in Tabriz, Iran. Three hundred and thirty women aged 15–49 years, married, non-pregnant, non-breastfeeding and not within the 6-week postpartum period with easy sampling were surveyed. The study was carried out in two gynecologic clinics, Alzahra and Talaghani, where women are referred for gynecologic examination or counseling.

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Data were collected by a questionnaire containing two sets. In the first part, data about UI and OVB were obtained by using UDI-6 and the following questions [2, 7, 8].

Overactive bladder without urinary incontinence was defined by: (1) answering ‘yes’ to one or both of the following questions: “On average do you urinate more than eight times a day and /or more than once during the night?” and “Have you had any urgency symptoms?”, but (2) answering ‘no’ to the question “Have you had any involuntary urinary loss during the last month?”.

If a woman answered ‘yes’ to all the three questions she was considered to have urinary incontinence. In particular, a positive answer to the following question was presumed to be an indication of stress incontinence: “Do you lose urine during sudden physical exertion, lifting heavy items, laughing, coughing or sneezing?” A positive answer to the following question was presumed to be urge incontinence: “Do you experience such a strong sudden urge to void that you leak before reaching the toilet?”. A positive answer to both questions was registered as mixed incontinence [2, 6, 7].

The reference group was created from those women who underwent the same routine gynecological examination in the same centers, but who had no symptoms related to urinary incontinence or overactive bladder and who answered ‘no’ to three questions mentioned above.

Then at the end of the first part of the questionnaire, medical, demographic and obstetrics history were gathered by interview. The patient was considered to have constipation if she defecated less than twice per week, with excessive straining. A patient was considered to have recurrent urinary tract infection if she reported two or more episodes per year of bacteriologically proven urinary tract infection [9].

The data for the second part of the questionnaire were obtained by examination. Pelvic organ prolapse was determined by using the pelvic organ prolapse quantification system (POPQ) [10, 11]. Stage zero and one were considered as good support. Pelvic measurements (perineal diameter, genital hiatus diameter, vaginal length, depth of posterior fornix) were determined using the POPQ system [10]. Pelvic floor muscle strength was determined too. Two-finger vaginal palpation was performed with the pelvic floor muscle relaxed. The woman was asked to contract her pelvic floor muscle as hard and long as she could around the examiner’s fingers. The pelvic floor muscle strength was rated as: (1) absent (no detectable muscle contractility around the examiner’s finger), (2) weak (contractility detectable but not all around the fingers), (3) moderate (contractility around the fingers but no elevation of pelvic organ), or (4) good (powerful contractility around the fingers and elevation of the pelvic floor) [10, 12]. The manual method used in this study is easy to learn and seems to have a high interobserver and intraobserver reliability [10, 12]. By bimanual palpation, the position of the uterus was assessed as antefelected, upright, retrofelected, uncertain or hystrectomised. All pelvic examinations were performed in the dorsal lithotomic position. Hemorrhoid was examined in the same position too. The varicose status was examined too. BMI was calculated as weight (kg)/height (m2). Connective tissue disorder was determined by using modified Carter-Wilkinson criteria [13].

To identify predictors of stress, urge, mixed and overactive bladder in all analysis, women with no incontinence served as the reference group.

In order to estimate sample size, we used previous prevalence of stress, urge, mixed incontinence and overactive bladder reported by epidemiological studies [2, 14, 15] (24%, 18%, 13%, 12% respectively). And the results were as follows: for overactive bladder = 35, urge urinary incontinence = 50, stress incontinence = 78, and mixed incontinence = 40. In order to confirm the reliability of the examination, the researcher and a gynecologist familiar with the pelvic organ prolapse quantification system performed a pilot study, and a kappa value of more than 0.7 was acquired.

Univariate logistic analysis was used to evaluate variables associated with each type of urinary incontinence. Those variables associated with incontinence (p < 0.05) were included in multivariate logistic regression models to explore predictors of different types of urinary incontinence and overactive bladder. SPSS/Win was used to analysis the data.

Results

To determine rate and related factors of stress, urge, mixed and overactive bladder, we evaluated 330 women. The average age of the women was 34.0 ± 8.4. The means of gravidity and parity were 3.8 ± 3.0 and 3.3 ± 2.5 respectively. Of the total, 77.3% were housekeepers and 25.2% were high school or college educated. One hundred and five (31.8%) had stress incontinence, 84 (25.5%) had urge incontinence, 64 (19.4%) had mixed incontinence, and 77 (23.3%) had overactive bladder. One hundred and forty eight (44.8%) were placed in the reference group.

Table 1 shows that the means of age, BMI and genital hiatus diameter were significantly more in women with all types of UI and OVB. The mean of vaginal length was more significantly in all types of UI but not OVB. The depth of posterior fornix was more significantly in women with stress incontinence. Perineal length showed no significant difference between control and cases.

Gravidity, delivery without episiotomy, vaginal delivery, and parity showed a significant relationship to stress, urge, mixed incontinence and OVB. Thus, with an increasing number of vaginal delivery, delivery without episiotomy, parity and gravidity from less than three to three or more, the prevalence of having stress, urge, mixed and OVB increased significantly. The weight of the largest infant delivered vaginally showed a relationship to stress and mixed incontinence but not to OVB and urge incontinence. Delivery with episiotomy and cesarean didn’t show any relationship to any of the cases (Table 2).

Education showed a significant relationship to all types of UI and OVB; with increasing education from elementary and guidance to high school and university, the prevalence of all types of UI and OVB decreased (p = 0.003). Employment showed a significant relationship to urge, stress and overactive bladder (p = 0.005) but not mixed. Exercise showed no relationship to any types of UI and OVB (p = 0.42). (Data not shown).

Table 3 reveals constipation, arthritis, diabetes mellitus, hypertension; UTI and anterior pelvic organ prolapse had a significant relationship to all types of UI and OVB. Posterior pelvic organ prolapse showed a relationship to all types of urinary incontinence but not to OVB. Apical prolapse showed no relationship to any types of UI and OVB. Obstructive pulmonary disease showed a significant relationship to stress and mixed incontinence but not to OVB and urge incontinence.

History of PID in the last year was significantly higher in those with overactive bladder and stress urinary incontinence. Although varicose and hemorrhoid were more prevalent in all types of UI and OVB, just varicose showed a significant relationship to urge incontinence. Familiar history of pelvic floor dysfunction and previous pelvic surgery (hysterectomy, urinary incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse) showed no relationship to any types of UI and OVB.

Pelvic floor muscle strength showed a significant relationship to all types of UI and OVB. Thus, with increasing pelvic muscle strength from zero or first degree to second or third, the prevalence of all types of UI and OVB decreased (p < 0.001). There was no relationship between uterine position with UI and OVB (data not shown).

Multiple logistic regression analysis showed posterior pelvic organ prolapse (OR = 2.8: CI = 1.25–6.35) vaginal delivery (OR = 1.4: CI = 1.2–1.7), constipation (OR = 2.5: CI = 1.1–5.8) as predictors of urge urinary incontinence (χ2 = 3.05, df = 8, P = 0.931). Interpreting these data shows that the odds of having urge urinary incontinence increased by 280% with posterior pelvic organ prolapse, by 40% with increasing vaginal delivery, and by 250% with constipation.

Posterior pelvic organ prolapse (OR = 3.7: CI = 1.6–8.5), pelvic floor muscle strength (OR = 0.4: CI = 0.2–0.8), vaginal delivery (OR = 1.3: CI = 1.0–1.6), constipation (OR = 2.6: CI = 1.2–0.01) and employment (OR = 2.6: CI = 1.0–0.8) were predictors of stress urinary incontinence (χ2 = 8.0, df = 8, P = 0.4). Interpreting these data shows that the risk of having stress urinary incontinence increases by 370% with posterior pelvic organ prolapse, by 4% with weak pelvic floor muscle strength, by 30% with vaginal delivery, by 260% with constipation, and by 260% with employment.

Vaginal length (OR = 1.8: CI = 1.1–1.8), vaginal delivery (OR = 1.8: CI = 1.4–2.2), constipation (OR = 2.8: CI = 1.0–7.8) were predictors of mixed urinary incontinence (χ2 = 12.2, df = 8, P = 0.143). Interpreting these data shows that the risk of having mixed incontinence increases by 80% with vaginal delivery, by 80% with higher vaginal length and by 280% with constipation.

BMI (OR = 1.1: CI = 1.02–1.8), constipation (OR = 2.3: CI = 1.1–4.9) and PID (OR = 2.1: CI = 1.0–4.6) were predictors of OVB (χ2 = 3.9, df = 8, P = 1.0). These data also show that the odds of OVB increase by 10% with increasing BMI, by 230% for subjects with constipation, and by 200% for those with history of PID in the last year.

Discussion

Some limitations of the study should be considered. Data about urinary leaking were obtained by interview [16], due to the fact that 74.8% of women were of a low educational standard. So in order to reduce bias, all the interviews were performed by a trained interviewer who was blind to the results of examination. It has been said that clinical history indicating stress and urge incontinence compared with urodynamic tests showed a sensitivity of 0.9 and 0.4 and a specificity of 0.5 and 0.6 respectively [2]. Although some misclassifications may have occurred due to the method of gathering data in this study, the magnitude and direction of this misclassification are difficult to estimate. Controls were not formally representative of the general population, but the fact that cases and controls were identified in the same settings, where similar selective mechanisms were likely to play a role, should have reduced the potential effect of selection bias. Another point to notice would be related to the rate of UI and OVB estimated in this study, which sounds to some extent higher than other studies: this could be related to using the interview technique of gathering data instead of urodyniamic tests, and also to the settings where patients referred more. It might even show that the rate of UI and OVB among our population could be higher than our expectation when really investigated.

The strong point of this study includes the fact that it presents information about determinants of different types of UI and OVB by including pelvic measurements and examination, using standard methods for recording the symptoms and data collection.

The results indicate that the risk of all types of UI increased with constipation. With regard to reproduction history, vaginal delivery increased the risk of stress, urge and mixed incontinence but not OVB. Posterior pelvic organ prolapse was associated with stress and urge incontinence. BMI and PID were associated with increased risk of OVB. Pelvic muscle strength was a predictor of stress urinary incontinence. Vaginal length was a predictor of mixed urinary incontinence.

The controversy persists as to whether urinary disorder is due to pregnancy or parity [2]. In the present study we found vaginal delivery to be a predictor of stress, urge and mixed incontinence. Episiotomy and cesarean didn’t show any relationship to UI and OVB, which might suggests their protective role.

We also found that posterior pelvic organ prolapse was related to urge and stress incontinence. The influence of central and posterior pelvic organ prolapse is more controversial. Diets et al. showed that entrocele had negative influence on flow [17]. This co-existence of vaginal prolapse and UI, which share their etiologic factors, can be regarded in order to reduce postoperative recurrence [18, 19].

Constipation showed a significant relationship to cases in this study. A similar association has been reported by some studies too [14, 20]. Pelvic floor muscle strength was related to all cases in univariate analysis, and was a predictor of stress incontinence. It has been suggested that pelvic muscle exercise and life style modification improve pelvic muscle strength [21, 22]. Employment also showed a significant relationship to stress incontinence. But 77% of our subjects were housekeepers, so it might indirectly reflect their life style rather than employment itself.

There was association between UTI and all types of UI and OVB in univaraite analysis. PID was also a predictor of OVB. Bacterial endotoxin and cystitis can have effects on contraction of urethra and cause detrusor hyperreflexia [22].

With regard to pelvic measurement, vaginal length was determined as a predictor of mixed incontinence. The mean of genital hiatus was significantly higher in all cases in univariate analysis. Two other studies also found an association between pelvic organ prolapse and genital hiatus [23, 24]. Data about the relationship between pelvic measurement and urinary disorders are lacking. It was not possible in this study to evaluate whether higher vaginal length and genital hiatus diameter were congenital or due to aging, delivery or pelvic organs prolapse.

Systemic diseases can have effects on urinary disorders [19]. We found diabetes mellitus, hypertension related to all types of UI and OVB in this study. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease was associated with stress and mixed incontinence.

There were low numbers of women with previous pelvic surgery in this study. Pelvic surgery is a controversial issue. It seems age still plays an important role; thus, in women under 60 years, no association was found between hysterectomy and urinary incontinence in a study [2]. We also didn’t find any association.

Between variables of arthritis, varicose, family history of pelvic floor dysfunction and connective tissue disorder, just arthritis and varicose showed a relationship to urinary disorders. Some relationships between joint pain, osteoporosis and cardiovascular factors with urinary disorders have been suggested [22, 25].

From this study in reproductive age women, we can suggest that improving pelvic muscle strength, treatment or prevention of constipation and posterior pelvic organ prolapse, having a healthy life style, optimal weight gain, treatment of UTI and PID and reducing number of vaginal deliveries can be possible positive measures in prevention of UI or OVB. Cesarean and episiotomy may have a protective role, but we weren’t able to determine their effect precisely in this study. Although vaginal length was determined as a predictor, measurement of genital hiatus is easy and can be suggested in evaluation steps. Further studies, preferably longitudinal, are suggested using urodynamic tests with larger sample size to evaluate urinary disorders.

References

Rechberger T, Postawshi K, Jakowicki JA, Gunja-Smith Z, Woessner JF (1998) Role of facial collagen in stress urinary incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol 179:1511–1540

Parazzini F, Chaaffarino F, Lavezzari M, Giambanco V (2003) Risk factors for stress, urge or mixed urinary incontinence in italy. B J Obstet Gyenecol 110:927–933

Olsen A, Smith VJ, Bergstrom JO, Colling JC, Clark AL (1997) Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol 89:501–506

Danforth KN, Townsend MK, Lifford K, Curhan GC, Resnik NM, Grodstein F (2006) Risk factors for urinary incontinence among middle-aged women. Am J Obstet Gynecol 194:339–345

Elia G, Bergman J, Bergman J, Dye TP (2002) Familial incidence of urinary incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol 187:50–53

Barber MD, Kuchibhatala MN (2001) Psychometric evaluation of two comprehensive condition-specific quality of life instruments for women with pelvic floor disorders. Am J Obstet Gynecol 185:1388–1395

Brocklehurst JC (1993) Urinary incontinence in the community—analysis of a MORI poll. BMJ 306:832–834

Wein AJ, Rovner ES (1999) The overactive bladder: an overview for primary care health provides. Int J Fertil 44:56–66

Brown JS, Grandy D, Quslander JG, Herzon AK, Varner ER, Posner SF (1999) Prevalence of urinary incontinence and associated risk factor in postmenopausal women. Obstet and Gynecol 94:66–70

Bump RC, Mattiasson A, Bo K (1996) The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organs prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol 175:10–17

Swift MD (2000) Distribution of pelvic organ support in a population of female subjects seen for routin gynecologic health care. Am Obstet Gynecol 183:277–285

Samuelsson EC, Victor FTA, Tibblin G, Svardsudd KF (1995) Sign of genital prolapse in a Swedish population of women 20–59 years of age and possible related factors. Am J Obstet Gynecol 85:225–228

Norton PA, Barker RN, Sharp HC, Warensky J (1995) Genitourinary prolapse and joint hypermobility in women. Obstet Gynecol 85:228–299

Zhu L, Lang JH, Wang H, Han SM, Liu CY (2006) The study on the prevalence and associated risk factors of female urinary incontinence in Beijing women. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 86:728–731

Duong TH, Korn AP (2001) A comparison of urinary incontinence among African American, Asian, Hispanic and white women. Am J Obstet Gynecol 184:1083–1086

Khan MS, Chalina C, Leskova L, Khullar V (2004) The relationship between urinary symptom questionnaires and urodynamic diagnosis: an analysis of two methods of questionnaire administration. B J O G 111:468–474

Dietz HP, Eldridge A, Grace M, Clarke B (2004) Does pregnancy affect pelvic organ mobility? Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 44:517–520

Bai SW, Jeen MJ, Kim JY, Chung KA, Kim SK, Park KH (2002) Relationship between stress urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J 13:256–260

Smith PP, Appell RA (2005) Pelvic organ prolapse and the lower urinary tract. The relationship of vaginal prolapse to stress urinary incontinence. Curr Urol Rep 6:340–347

Ewings P, Spencer S, Marsh H, Sullivan M (2005) Obstetric risk factors for urinary incontinence and preventive pelvic floor exercises: Cohort study and nested randomized controlled trail. J Obstet Gynecol 25:558–564

Dolan LM, Hosker GL, Mallett VT, Allen RT, Smith ARB (2003) Stress incontinence and pelvic floor neurophysiology 15 years after the first delivery. BJOG 110:1107–1114

McGrother CW, Donaldson MM, Hayward T, Matthews R, Dallosso HM, Hyde C (2006) Urinary storage symptoms and co morbidities: a Prospective population cohort study in middle-aged and older women. Age Ageing 35:16–24

Digesu GA, Khullar V, Hutchings A, Stantamato S, Selvaggi L (2001) Vaginal prolapse and its symptoms: how do they correlate? 132 Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 12(suppl 1):132

Vakili B, Zhenj YT, Loesch ZH, Echols KL, Franco N, Chesson RR (2005) Levator contraction strength and genital hiatus as risk factors for recurrent pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol 192:1592–1598

Maclennan AH, Taylor AW, Wilson D (2000) The prevalence of pelvic floor disorders and their relationship to gender, age, parity and mode of delivery. B J Obstet Gynecol 107:1460–1470

Acknowledgment

The support provided by the Research Department of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences is gratefully acknowledged. The co-operation of Mr. Rostam Khanee is greatly acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sobhgol, S.S., Charandabee, S.M.A. Related factors of urge, stress, mixed urinary incontinence and overactive bladder in reproductive age womenin Tabriz, Iran: a cross-sectional study. Int Urogynecol J 19, 367–373 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-007-0437-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-007-0437-2