Abstract

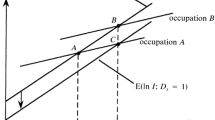

The central idea of the present study is to re-establish the importance of human capital variables (education and experience) at all India level and also at the disaggregated level of gender (male/female) across regular and casual workers using NSS 68th round. This is the latest employment–unemployment unit-level records pertaining to year 2011–2012. The paper examines the impact of human capital variables, household factors, job-related factors, individual characteristics and locational factors on earnings of an individual. Separate augmented Mincerian equations have been used for regular and casual workers, further subdivided at the level of male and female. The method of quantile regression has been used to estimate the augmented Mincerian equation at the above-mentioned disaggregated levels. The present study showcases that human capital variables, household factors, job-related factors, individual characteristics and locational factors impact regular and casual workers differently, the variation being further pronounced when disaggregated at the level of gender. Interestingly, human capital variables impact the earnings of regular workers (male and female) and casual (male and female) workers positively. Factoring the growing informalisation (not being entitled to social security benefits) in the regular form of employment, the study showcases a wide disparity within the regular workers. Thus, an attempt has been made to unfold primarily the interplay between education and earnings at various disaggregated levels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

NSS 68th round unit-level records do not provide whether workers are in the organise/unorganised sectors, and it furnishes information whether they are in casual/regular employment, self-employed or unemployed.

Classification on similar logic was done in Dutta (2006) using 1999 NSS survey. The findings revealed 57 % regular workers employed in enterprises that were public, semi-public or otherwise in the registered or organised sector but only 11.4 % of casual workers were so employed.

Figures are author’s calculation using NSS 68th round unit-level records.

Nine one-digit occupational classifications have been made using NCO 2004 codes.

Those workers receiving any form of social security benefits have been classified as formal and those without social security benefits have been classified as informal (this classification has been done in case of regular workers). I am thankful to the anonymous referees for suggesting the above classification.

A regular wage salaried worker is a person who works in others’ farm or non-farm enterprises (household and non-household) and in return received salary or wages on a regular basis, while a casual worker is a person who is engaged in others’ farm or non-farm enterprises (household and non-household) and in return, received wages according to the terms of the daily or periodic work contract.

Casual labour = individuals working as: casual wage labour in public works other than Mahatma Gandhi NREGS public works; casual wage labour in Mahatma Gandhi NREGS public works; and casual wage labour in other types of works (comprising of codes 41, 42, 51)

Regular workers = worked as regular salaried/wage employee (comprising of codes 31, 71, 72).

The figures for the other quantiles can be interpreted similarly.

The present study marks a departure wherein a subsequent higher level of education is associated with higher earnings even for casual workers.

The description of the variables is mentioned in Table 1. Household head’s level of education has not been incorporated owing to the fact that two-thirds of all households are single-worker household and nuclear family constitutes a substantial portion of single regular workers’ household. In such cases, there is greater possibility of spurious correlation between workers’ education variable and educational level of the head of the household variable. I am thankful to the anonymous referee for the suggestion.

For casual workers in the lower quantiles, caste affiliation does not play a significant role; it proves to be disadvantageous in the higher quantiles.

For both regular and casual workers, the wage disadvantage increases with higher quantiles.

From the above-mentioned studies, only Azam’s (2009) study has done a quantile regression. None of the studies have taken casual workers.

These studies have not done a regular/casual analysis.

Elementary occupation comprises of sales and services, agricultural, fishery and related labourers, labourers in mining, construction, manufacturing and transport.

Skilledagr comprises of market-oriented skilled agriculture and fishery workers, subsistence agriculture and fishery workers.

This concept of embodied social capital was based on a study in Trinidad of low-wage workers in which it was seen that individuals do not see differences of ethnicity and gender as a social construction, rather accept them as factual true realities created by biology and heredity.

The studies by Blom et al. (2001) in Brazil, Riboud et al. (2007) in India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka, Mehta et al. (2007) in Thailand, Philippines, Fiszbein et al. (2007) in Argentina, Behrman et al. (2003) in 18 Latin American countries, and (Topel 1999) in Brazil, Chile, Mexico, Korea, Taiwan, Indonesia, Thailand, China showed that the rate of return for higher education and higher secondary education started rising in the 1990s and that of primary and lower secondary education dropped. None of the studies referred above and in the main text used the formal/informal dummy and therefore the rate of return figures vary across quantile groups.

In 1990, 1999 and 2007, there was an increase in supply of workers with completed primary education to the tune of 75, 80 and 86 % of the age group, respectively (Colclough et al. 2010).

The rates of return on OLS coefficients(not reported due to lack of space) shows increase in rates of return with consecutive higher levels of education, it is 2.15, 6.75, 6.98 and 9.96 %, respectively, for elementary, secondary, higher secondary and graduation and above. Disaggregation at the level of quantile showcases a different result.

References

Acemoglu D (2002) Technical change, inequality and the labour market. J Econ Lit 40:7–72

Agrawal T (2011) Returns to education in India: some recent evidence. Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research. Working Paper 2011-017, Mumbai

Anker R (2001) Theories of occupational segregation by sex: an overview. In: Loutfi MF (ed) Women, gender and work: what is equality and how do we get there. International Labour Organisation, Geneva

Azam M (2009) Changes in wage structure in urban India 1983–2004: a quantile regression decomposition. IZA DP no. 3963

Azam M, Prakash N (2010) A distributional analysis of the public private wage differential in India. IZA DP no. 5132

Banerjee B, Knight JB (1985) Caste Discrimination in the Indian labour market.J Dev Econ 17:277–307

Becker GS (1964) Human capital. National bureau of economic research. Columbia University Press, New York

Behrman JR, Wolfe BL (1984) Labour force participation and earnings determinants for women in the special conditions for developing countries. J Dev Econ 15:259–288

Behrman JR, Khan S, Ross D, Sabot R (1997) School quality and cognitive achievement production: a case study for rural Pakistan. Econ Educ Rev 16(2):127–142

Behrman J, Birdsall N, Szekely M (2003) Economic policy and wage differentials in Latin America. Centre for Global Development. Working Paper No. 29. Washington

Bennell P (1996) Using and abusing rates of return: a critique of the world bank’s 1995 education sector review. Int J Educ Dev 16(3):235–248

Bender KA (1998) The central government-private sector wage differential. J Econ Surv 12(2):177–220

Berger S, Piore MJ (1980) Dualism and discontinuity in industrial societies. University of Cambridge Press, New York

Bhattacharya BB, Sakthivel S (2004) Regional growth and disparity in India, comparison of pre and post reform decades. Econ Polit Wkly 39(10):1071–1077

Blaug M, Layard PRG, Woodhall M (1969) Education and employment problems in developing countries. ILO, Geneva

Block F, Kuskin M (1978) Wage determination in the union and nonunion sectors. Ind Labor Relat Rev 31:183–192

Blom A, Nielsen LH, Verner D (2001) Education, earnings, and inequality in Brazil, 1982–1998: implications for education policy. Peabody J Educ 76(3):180–221

Brown PH (2006) Parental education and investment in children’s human capital in rural China. Econ Dev Cult Change 54(4):759–789

Buchinsky M (1998) Recent advances in quantile regression models. J Human Resour 33(1):88–126

Card D (1999) The causal effect of education on earnings. In: Ashenfelter O, Card D (eds) Handbook of labour economics. North−Holland, Amsterdam

Chakravorty S, Lall S (2007) Made in India: the economic geography and political economy of industrialization. Oxford University Press, New Delhi

Chamarbaghwala R (2009) Economic liberalization and urban rural inequality in India: a quantile regression analysis. Empir Econ 39:371–394

Chant S (1991) Women and survival in Mexican Cities. Manchester University Press, Manchester

Chiswick BR (1986) Comment on Hauser and Sewell. J Labour Econ 4:s116–s120

Chiswick BR (2003) Jacob Mincer, experience and the distribution of earnings. IZA DP No. 847

Cohn E, Addison JT (1997) The economic returns to lifelong learning. Working paper B−97−04, Division of Research, University of South Carolina College of Business Administration)

Cohn E, Addison JT (1997) The economic returns to lifelong learning. University of South Carolina College of Business Administration Division of Research Working Paper, South Carolina

Colclough C et al (2010) The changing pattern of wage returns to education and its implications. Dev Policy Rev 28(6):733–747

Das MB (2003) Ethnicity and social exclusion in job outcomes in india: summary of research findings, unpublished paper, World Bank Institute

Datta RC (1981) Education and income distribution, Department of Economics, University of Bombay. Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis

Denison E (1964) Measuring the contribution of education and the residual to economic growth. The Residual Factor and Economic Growth, Paris. OECD

Deshpande S, Deshpande L (1998) Impact of liberalisation on labour market in India: What do facts from NSSO's 50th round show? Econ Political Wkly 33(22):31–39

Dickens WT, Lang K (1985) A test of dual labor market theory. Am Econ Rev 75(4):792–805

Divakaran S (1996) Gender based wage and job discrimination in urban India. Indian J Labour Econ 39(2):235–257

Duraisamy P (2002) Changes in returns to education in India, 1983–94: by gender, age−cohort and location. Econ Educ Rev 21(6):609–622

Duraisamy M, Duraisamy P (1993) Returns to scientific and technical education in India. Margin 7(1):396–406

Duraisamy P, Duraisamy M (1995) Returns to higher education in India. J Educ Plan Adm 9(1):57–68

Duraisamy P, Duraisamy M (2005) Regional differences in Wage Premia and returns to education by gender in India. Indian J Labour Econ 48(2):335–347

Duraisamy P, Duraisamy M (2014) Occupational segregation, wage and job discrimination against women across social groups in the Indian labor market: 1983–2010. Preliminary Draft

Duraisamy P, Duraisamy M (2016) Gender wage gap across the wage distribution in different segments of the Indian labour market, 1983–2012: exploring the glass ceiling or sticky floor phenomenon. Appl Econ

Dutta PV (2004) The structure of wages in India, 1983–1999. Poverty research unit at Sussex. Working paper No.25

Dutta PV (2006) Returns to education: new evidence for India, 1983–1999. Educ Econ 14(4):431–451

Elliott RF, Duffus K (1996) What has been happening to pay in the public sector of the British economy? Developments over the period 1970–1992. Br J Ind Relat 34:51–85

Faish T, Kingdon G et al (2012) Heterogeneous returns to education in the labour market. World Bank. Working Paper 6170

Falaris EM (2008) A quantile regression analysis of wages in Panama. Rev Dev Econ 12(3):498–514

Fiszbein A, Patrinos HA, Giovagnoli PI (2007) Estimating the returns to education in Argentina using quantile regression analysis: 1992–2002. Economica 53(1–2):53–72

Goel SC (1975) Education and economic growth. Macmillan, New Delhi

Gordon DM (1972) Theories of poverty and underemployment: orthodox radical and dual labour market perspectives. Lexington books, Lexington

Glinskaya E, Lokshin M (2007) Wage differentials between the public and private sectors in India. J Int Dev 19(3):333–355

Griliches Z (1970) Notes on the role of education in production functions and growth accounting. In: Lee Hansen W (ed) Studies in income and wealth, vol 35. Colmnbia University Press, New York

Griliches Z (1977) Estimating the returns to schooling: some econometric problems. Econometrica 45(1):1–22

Griliches Z, Mason W (1972) Education, income and ability. J Polit Econ 80(3):74–103

Gregory R, Borland J (1999) Recent development in public sector labour markets. In: Ashenfelter O, Card D (eds) Handbook of Labour Economics. vol 3c. Elsevier, North Holland

Gronau R (1974) The effect of children on the housewife’s value of time. In: Schultz TW (ed) Economics of the family. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Harberger AC (1965) Investment in men versus investment in machines: the case of India. In: Anderson CA, Bowman MJ (eds) Education and economic development. Aldine Publishing Company, Chicago, pp 11–50

Hartog J, Pedro TP, Vieira JAC (2001) Changing returns to education in Portugal during the 1980s and Early 1990s: OLS and quantile regression estimators. Appl Econ 33(8):1021–1037

Heckman J (1979) Sample selection bias as specification error. Econometrica 47(1):153–161

Heckman J, Hotz V (1986) An investigation of the labour market earnings of Panamanian males: evaluating the sources of inequality. J Hum Resour 21(4):507–542

Hill M (1979) The wage effects of marital status and children. J Hum Resour 14:579–594

Husain IZ (1967) Returns to education in India: an estimate. In: Singh VB (ed) Education as investment. Meenakshi Prakashan, Meerut

Institute of Human Development (2014) India labour and employment. Workers in the era of globalization

Kabeer N (2002) Safety nets and opportunity ladders: addressing vulnerability and enhancing productivity in South Asia. Overseas Development Institute, Working Paper 159

Karan AK, Selvaraj S (2008) Trends in wages and earnings in India: Increasing wage differentials in a segmented labour market. ILO-Pacific Working Paper series, New Delhi

Katz L, Krueger A (1993) Public sector pay flexibility: labour market and budgetary consideration. Pay flexibility in the public sector. OECD, Paris

Khanna,S.(2012).Gender wage discrimination in India: glass ceiling or sticky floor? Working Paper No. 214. Centre for Development Economics. Delhi School of Economics

Kijima Y (2006) Why did wage inequality increase? Evidence from urban India 1983–99. J Dev Econ 81:97–117

Killingsworth MR (1983) Labor supply. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Kingdon GG (1997) Labour force participation, returns to education and sex discrimination in India. Indian J Labour Econ 40(3):507–526

Kingdon GG (1998) Does the labour market explain lower female schooling in India? J Dev Stud 35(1):39–65

Kingdon G, Theopold N (2008) Do returns to education matter to schooling participation? Evidence from India. Educ Econ 16(4):329–350

Kingdon G, Unni J (2001) Education and women’s labour market outcomes in India. Educ Econ 9(2):173–195

Koenker R, Bassett G (1978) Regression quantiles. Econometrica 46(1):33–50

Koenker R, Hallock K (2001) Quantile regression. J Econ Perspect 15(4):143–156

Kothari VN (1967) Returns to education in India. In: Singh VB (ed) Education as investment. Meenakshi Prakashan, Meerut, pp 127–140

Lakshmanasamy T, Ramasamy S (1999) An econometric analysis of the worker choice between public and private sector. Indian J Labour Econ 42(1):71–83

Lemieux T (2006) The Mincer equation thirty years after schooling, experience, and earnings. In: Grossbard−Shechtman S (ed) Jacob Mincer: a pioneer of modern labor economics. Springer Verlag, London

Lucas R (1988) On the mechanics of economic development. J Monet Econ 22:3–42

Madheswaran S (1998) Earning differentials between public and private sector in India. Indian J Labour Econ 41(4):945–970

Machado JAF, Mata J (2001) Earning functions in Portugal 1982–1994: evidence from quantile regressions. Empir Econ 26(1):115–134

Madheswaran S, Attewell Paul (2007) Caste discrimination in the Indian urban labour market: evidence from the national sample survey. Econ Polit Wkly 42(41):4146–4153

Madheswaran S, Shroff S (2000) Education, employment and earnings for scientific and technical workforce in India. Indian J Labour Econ 43(1):121–137

Malathy R (1983) Women’s allocation of time to market and non−market work: a study of married women in Madras City, Ph.D. thesis, University of Madras, India

Manski C (1989) Anatomy of the selection problem. J Hum Resour 24(3):343–360

Martins PS, Pereira PT (2004) Does education reduce wage inequality? Quantile regression evidence from 16 countries. Labour Econ 11:355–371

Mehta AJ, Felipe PQ, Camingue S (2007) Changing patterns in Mincerian returns to education and employment structure in three Asian countries. Institute for Social, Behavioral and Economic Research. Centre for Global Studies. University of California, Santa Barbara

Mincer JA (1974) Schooling, experience and earnings. NBER. http://www.nber.org/chapters/c1765.pdf

Moenjak T, Worswick C (2003) Vocational education in Thailand: a study of choice and returns. Econ Educ Rev 22:99–107

Montenegro C (2001) Wage Distribution in Chile: does gender matter? a quantile regression approach. Policy Research Report on Gender and Development. Working Paper 20. World Bank

Mwabu G, Schultz TP (1996) Education returns across quantiles of the wage function: alternative explanations for returns to education by race in South Africa. Am Econ Rev 86(2):335–339

Mwabu G, Schultz TP (2000) Wage premiums for education and location of South African workers, by gender and race. Econ Dev Cult Change 48(2):307–334

Nallagounden AM (1967) Rate of return on investment in education in India. In: Hansen WL (ed.) Symposium on the rate of return to investment in education. J Hum Resour 2(3): 291–374

Nayak P (1994) Economic development and social exclusion in India. Paper presented at the Second Workshop on Patterns and Causes of Social Exclusion and the Design of Policies to Promote Integration, Cambridge, 14–18 July 1994

Papola TS (1986) Women workers in the formal sector of Lucknow India. In: Auker R, Hein C (eds) Sex inequalities in Urban employment in the developing world. Hampshire and London. Mcmillan and Geneva. ILO

Papola TS (2012) Social exclusion and discrimination in the labour market. Institute for Studies in Industrial Development. Working paper 2012/04

Panchmukhi PR, Panchmukhi VR (1969) Socio economic variables and urban incomes. In: Pandit HN (ed) Measurement of cost productivity and efficiency of education. NCERT, New Delhi

Paul T, Raju S (2014) Gendered labour in India: diversified or confined? Econ Polit Wkly 49(29):197

Psacharopoulos G (1985) Returns to education: a further international update and implications. J Hum Resour 20:583–604

Psacharopoulos G (1994) Returns to investment in education: a global update. World Dev 22:1325–1343

Psacharopoulos G, Patrinos HA (2002) Returns to investment in education: a further update. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 2881

Riboud M, Savchenko Y, Tan H (2007) The knowledge economy and education and training in South Asia: a mapping exercise of available survey data. South Asia Human Development Department. World Bank, Washington

Romer PM (1990) Endogenous technological change. J Polit Econ 98(Supplement):S71–S102

Rosen S (1986) The theory of equalizing differences. In: Ashenfelter OC, Layard R (eds) Handbook of labor economics, vol 1. Elsevier, New York, pp 641–692

Sahota GS (1962) Returns to education in India, Asian Workshop Paper No. 6–11 (University of Chicago) mimeo

Schager N (1993) An overview and evaluation of flexible pay policies in the Swedish public sector. Pay flexibility in public sector. OECD, Paris

Schultz TW (1960) Capital formation by education. J Polit Econ 68:571–583

Schultz T (1963) The economic value of education. Columbia University Press, New York

Schultz T (1964) Transforming traditional agriculture. Yale University Press, New Haven

Schultz TP (1993) Returns to women’s education. In: Women’s education in developing countries: barriers, benefits, and policies’. Johns Hopkins University Press for the World Bank, Baltimore and London

Schultz TP (2003) Evidence of returns to schooling in Africa from household surveys: monitoring and restructuring the market for education. Economic Growth Centre. DP no. 875

Sebastian A (2005) Gender, education and employment: an analysis of higher education and labour market outcome in Kerala. Indian J Labour Econ 48(2):871–885

Siphambe HK (2000) Rates of return to education in Botswana. Econ Educ Rev 19:291–300

Sood A et al (2014) Deregulating capital, regulating labour: the dynamics in the manufacturing sector in India. Econ Polit Wkly 49(26&27):58–68

Spence M (1974) Market signalling. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Srivastava N, Srivastava R (2009) Women,work and employment outcomes in rural India. Paper presented at the FAO-IFAD-ILO workshop. Rome. http://www.faoilo.org/fileadmin/user_upload/fao_ilo/pdf/Papers/17_March/Srivastava_Final.pdf. Accessed 24 Aug 2016

Smith SP (1976) Pay differentials between federal government and private sector workers. Ind Labour Relat Rev 29(2):179–197

Smith SP (1977) Equal pay in the public sector: Fact or fantasy? Industrial relations section. Princeton University

Tansel A (2005) Public private employment choice, wage differentials and gender in Turkey. Econ Dev Cult Chang 52(2):453–477

Talbert J, Bose C (1977) Wage−attainment processes: the retail clerk case. Am J Sociol 83:403–424

Tansel A, Bircan F (2010) Wage inequality and returns to education in Turkey: a quantile regression analysis. Discussion Paper Series, IZA

Taubman P, Watcher ML (1986) Segmented labour markets. In: Ashenfelter O, Layard R (eds) Handbook on labour economics, vol 2. North Holland, Amsterdam

Tendulkar SD (2003) Organised labour market in India: pre and post reform. Anti poverty and social policy. Alwar, India

Tilak JBG (1987) The economics of inequality in education. Sage Publications, New Delhi

Tilak JBG (2002) Building human capital in East Asia: what others can learn. NIEPA, New Delhi

Topel R (1999) Labour markets and economic growth. In: Ashenfelter O, Card D (eds) Handbook of labour economics. North Holland, Elsevier

Unni J, Rani U (2001) Social protection for informal workers. J Labour Econ 44:559–575

Uzawa H (1965) Optimum technical change in an aggregative model of economic growth. Int Econ Rev 6:18–31

Weiss TJ (1986) Revised estimates of the United States Workforce, 1800–1860. NBER chapters. In: Long term factors in American Economic Growth. National Bureau of Economic Research, pp 641–676

Welch F (1974) Black white earnings differential in rates of return to schooling. Am Econ Rev 63(5):893–907

Yelvington KA (1995) Producing power:Ethnicity, gender and class in a Caribbean workplace. Temple University Press. Philadelphia

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mitra, A. Education and earning linkages of regular and casual workers in India: a quantile regression approach. J. Soc. Econ. Dev. 18, 147–174 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40847-016-0029-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40847-016-0029-4