Abstract

Since the introductory article for what has become known as the “service-dominant (S-D) logic of marketing,” “Evolving to a New Dominant Logic for Marketing,” was published in the Journal of Marketing (Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2004a)), there has been considerable discussion and elaboration of its specifics. This article highlights and clarifies the salient issues associated with S-D logic and updates the original foundational premises (FPs) and adds an FP. Directions for future work are also discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the few years since we published the first article on what has become known as “service-dominant (S-D) logic,” “Evolving to a New Dominant Logic for Marketing” (Vargo and Lusch 2004a), there has been substantial concurrence, debate, dialog, and inquiry. These varied responses began with the seven commentaries invited by Ruth Bolton (2004), the Journal of Marketing editor who published the article. Additionally, in the publication of The Service-Dominant Logic of Marketing: Dialog, Debate and Directions (Lusch and Vargo 2006b), 50 well-recognized scholars reacted and responded to and elaborated S-D logic. The reactions and elaborations continued in the Otago Forum on Service-Dominant Logic held in New Zealand during November 2005 and the special issue of Marketing Theory (Aitken et al. 2006) that resulted from that forum. They continue with this special issue of the Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, for which we received approximately 70 submissions. Interestingly, although the call-for-papers solicited manuscripts on the broad theme of “new logics” for marketing the preponderance of the submissions were centered on the S-D logic of marketing.

Most of the responses and comments have been generally supportive, if not favorable. Others have been more cautious, if not skeptical, at least about specific aspects of S-D logic as originally presented. A few have been more critical, either generally or in relation to specific aspects.

We have always claimed that we do not “own” S-D logic but rather that it is more of an open-source evolution that we tried to identify, punctuate, and advance in our initial article and then elaborate and refine through subsequent work, while encouraging other scholars to do the same. Thus, we have tried to remain as open to comments of skepticism and criticism as we, naturally, have been to praise. In some cases we have found that the S-D logic thesis or some of its components have been misunderstood. More often, we have found that the insightful comments of our colleagues have offered opportunities for refining and enhancing the specifics of S-D logic as we originally presented it. With a few exceptions (e.g., Lusch and Vargo 2006a; Vargo and Lusch 2006), while we have acknowledged legitimate issues with some of the original wording of some of the foundational premises (FPs) of S-D logic, we have avoided changing them to avoid the confusion likely to follow a series of isolated modifications in multiple articles. However, we feel that this issue of JAMS provides an appropriate venue for addressing the most central issues and providing essential modifications.

The purpose of this commentary is to explore the major issues surrounding S-D logic and to offer revisions to the FPs as published in the 2004 JM article. First, we discuss several general issues and concerns that have been raised. Second, we explain and elaborate several misunderstandings that we have found to be relatively common. We then offer modifications to the original FPs, add one FP, and provide explanation in some cases where we do not feel either a modification or addition is warranted. Finally, we point toward some directions that the development of S-D logic could (should) take.

General issues

There have been several relatively salient themes that we have noted in the suggested refinements for S-D logic. Among these are the (1) observation that some of the wording of the original FPs is overly reliant on a goods-dominant (G-D) logic lexicon, (2) concern that we were overly managerial in our approach, especially as reflected in the wording of some FPs, (3) suggestion that we need to more explicitly recognize the interactive, networked nature of value creation, and (4) observation that we were not sufficiently explicit in our acknowledgement of value creation being phenomenological and experiential in nature. There is an additional general issue of whether “service” is the proper designator of the “new dominant logic.” Because of the central importance of that issue, it is dealt with separately in this special issue (Vargo and Lusch in this issue). The others are addressed here.

S-D logic’s G-D lexicon

As discussed elsewhere (Vargo and Morgan 2005), since at least the time of Smith’s (1776) declaration that “productive” meant the creation of surplus tangible goods that could be exported to enhance national wealth, the lexicon of economics, business, and society in general (in its discussion of business) has developed around a logic of tangible goods. The goods-centric nature of the language of commerce can be seen in the core lexicon: “product,” “production,” “goods,” “supplier,” “supply chain,” “value-added,” “distribution,” “producer,” “consumer,” etc. This foundational lexicon reflects more than just words available to talk about goods; it reflects an underlying paradigm for thinking about commerce, marketing, and exchange in general. This presents a problem for any attempt at discussing and describing a counter-paradigmatic view, such as S-D logic. Often, there are no generally acceptable, counter-paradigmatic, or even neutral, words available. Thus, it often becomes convenient, if not necessary, to employ a G-D logic lexicon to describe an S-D logic foundation.

As we have further discussed and elaborated our view of S-D logic since “Evolving...” (Vargo and Lusch 2004a) was published, we have caught and corrected some of the more critical lexicographic slips that had become apparent. Examples are the change of FP6 from “The customer is always a co-producer” to “The customer is always a co-creator of value” (Vargo and Lusch 2006) and the more subtle, but critical shift from the use of the (plural) term “services” (reflecting a special type of output—intangible product) to the (singular) term “service” (reflecting the process of using one’s resources for the benefit of another entity) (Vargo and Lusch 2004b, 2006).

Some terms we did not judge to be sufficiently critical to warrant changing in isolation. An example is the use of the phrase “unit of exchange” (see also Ballantyne and Varey 2006) in FP1, a change we make below. Others are more problematic because suitable language is hard to find. For example, the terms “producer” and “consumer” are clearly inconsistent with S-D logic’s co-creation of value premise. Yet, at least since The Otago Forum, we have been asking for suggestions for S-D logic-friendly alternatives. To date, none has emerged, so we find ourselves using some combination of “actor” “firm,” “provider,” “customer,” “beneficiary,” or similarly connotatively imprecise labels. Still other issues of language, both in the FPs and their discussion, will likely continue to emerge. Kohli (2006, p. 291) captures the importance of this issue of language:

I would like to underscore a critical observation made by Vargo and Lusch 2006 regarding lexicons. Our thinking is profoundly influenced, indeed trapped, by the words we use and the images they evoke. It is crucial that we find new labels and phrases that help us think and conceptualize afresh.

We agree.

The managerial phrasing of S-D logic

There have been a number of comments that, as presented, S-D logic is firm-centric and managerially oriented. These observations are at least partially correct. Marketing, by almost any definition, is a professional and applied discipline (Hunt 1992). Application implies a normative orientation and normative implies a constituency. Additionally, the Journal of Marketing, in which the first S-D logic article was published, is a managerially oriented journal. Thus, the “S-D logic of marketing,” as presented, appropriately, has a somewhat managerial and firm-centric slant. However, this acknowledgement does not mean that S-D logic is applicable only to managers, or even only to marketing (see Vargo and Lusch 2006).

The more pertinent, general issue is not that the S-D logic of marketing is overly managerially marketing oriented, but rather that there is a need for a more robust (than economics) positive foundation (Vargo 2007) for the development of normative theory that can inform marketing managers as well as other constituencies, such as public policy makers. Venkatesh et al. (2006, p. 252) perhaps capture the central issue best in their contention that in the marketing literature the “term market is everywhere and nowhere.” Stated somewhat differently, while application must be firm—(or customer, or societal, etc.) centric, understanding should be market-centric. Thus, what is needed is a general theory of the market. We contend that S D logic is a generalizable mindset from which a general theory of the market can be developed; the S D logic of marketing is a specific application of the logic. We (Lusch and Vargo 2006c; Vargo and Lusch 2006) have also suggested that S-D logic could provide the foundation for a revised theory of the firm (and other resource-integrating activities), a theory of service systems (see also Maglio and Spohrer in this issue), and a revised theory of economics and society.

Having said this, for reasons discussed, some of the wording in the original FPs is a little unnecessarily firm centric, or at least G-D-logic-lexicon driven. These issues are addressed further in later sections (see also Vargo and Lusch 2006).

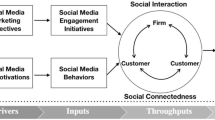

Interactive and networked nature of value creation

As noted in Lusch and Vargo (2006a), several scholars (e.g., Achrol and Kotler 2006; Gronroos 2006; Gummesson 2006) have pointed out that we were not as explicit about the interactive and networked nature of value creation and exchange as might be appropriate. We agree. As we also noted then, “it is not so much that S-D ignores interaction and networks as it deals with them somewhat implicitly” (Vargo and Lusch 2006, p. 285).

The interaction orientation is clearly present in FP6 (as restated in Vargo and Lusch 2006): “The customer is always a co-creator of value.” It is also implied by the relational orientation specified in FP8. The network orientation is somewhat more oblique, if not opaque, but is implied in FP2 where it is indicated that indirect exchange masks the nature of exchange. That is, indirect exchange implies networks or, as we stated originally: “Over time, exchange moved from one-to-one trading of specialized skills to the indirect exchange of skills in vertical marketing systems and increasingly large, bureaucratic hierarchical organizations” (Vargo and Lusch 2004a, p.8). Thus, value networks and constellations, as we later argued (e.g., Lusch and Vargo 2006c), will continue to mask the fundamental nature of exchange. In addition, networks are implied in the original FP9—“Organizations exist to integrate and transform micro-specialized competences into complex services that are demanded in the marketplace—but becomes more apparent in its almost immediate restatement (Lusch and Vargo 2006a, p. 283–4)—“all economic actors (e.g., individuals, households, firms, nations, etc.) are resource integrators.”

We made the interaction and networks, and thus the relational nature of value creation, to S-D logic considerably more central and explicit in subsequent writing (e.g., Lusch and Vargo 2006a, c) and in numerous presentations. For instance we show (Lusch and Vargo 2006c, p. 411) the close link between specialization and the exchange of service for service and networks and interaction.

...as the division of labor increased, another important development occurred—the connectedness of individuals. As each person specializes we become more dependent and connected to others. Thus both the extent of the market and the density of the network of interconnections is a function of the division of labor in society.

We more directly emphasize interactivity and networks by formal inclusion in the revised FPs and related elaborations of this update. Michel et al., in their discussion of discontinuous innovation, in which reconfigured value constellations are common, and the writing of Payne et al. (both in this issue), on managing the co-creation of value, also contribute to the discussion of the network nature of value creation.

The phenomenological/experiential nature of value

We have always considered value to be phenomenologically determined. We believe that this orientation is implied by the term “service,” as we have defined it. It is also reflected in the JM (Vargo and Lush 2004a) article in the use of terms like “consumer’s perceptions,” “meeting higher-level needs,” “customer determination,” “co-creation,” etc., in conjunction with the discussion of “service” to capture its phenomenological nature and idiosyncratic determination. Yet, we acknowledge that “experience” is perhaps a more contemporarily specific and descriptive term. In the JM article, our focus was on the connection between a market provider and a market beneficiary (value co-creator)—that is, on the service provision process—rather than the specifics of how value is uniquely and contextually interpreted. Some (e.g., Shembri 2006) construed this single-article treatment as evidence that we considered value-determination by the customer to be entirely “rationalistic,” which we do not. Others, perhaps based on a more extensive review of S-D logic literature, found it relatively easy to make the connections between what we were advocating and a more interpretivistic perspective. For example, Arnould (2006, p. 293–4) recognized the connection in his contention that S-D logic and Consumer Culture Theory are “natural allies.”

“Vargo and Lusch’s (2004a) premise three: ‘Goods are Distribution Mechanisms for Service Provision’, recalls Sid Levy’s ‘Symbols for Sale’ (1959). In this text (foundation) of Consumer Culture Theory, he asserted that people buy things for what they mean...Premise three, like the definition of service itself (Vargo and Lusch 2006b, p. 4), also recalls Deighton’s (1992) contention that people don’t buy objects, but instead buy performances. CCT researchers [are in a position to] understand how consumers perform service with firm-provided offerings.

Regardless, we find the term “experience” closer to our intended meaning than were the words that we had originally used. In fact, it is the term we have increasingly used (Vargo and Lusch 2004b; Lusch et al. 2007). However, for reasons discussed below, we find the term “phenomenological,” arguably, more precise, or at least less subject to multiple connotations.

In a similar vein, Penaloza and Venkatesh (2006) suggest the term “meaning” to capture both phenomenological interpretation and cultural context. Like Arnould’s (2006) amplification, we believe that Penaloza and Venkatesh’s elaboration of S-D logic provides enrichment to the underlying framework. We make our experiential/phenomenological understanding of value more explicit in our modification of the FPs in this commentary.

Misunderstandings or misinterpretations

In Vargo and Lusch (2006), we discussed several misunderstandings about S-D logic. Generally, we point the interested reader to that chapter. However, several issues are so central that they are worthy of emphasis here. Among these are the ideas that (1) S-D logic is necessitated and/or justified by the fact that we have entered a “services economy,” (2) the notion that S-D logic applies only to dyadic, firm/customer exchange, and (3) the contention that S-D logic does not accommodate or pay sufficient attention to social and nonprofit marketing and marketing ethics. These issues are discussed below.

The “Services Economy” justification of S-D logic

Perhaps one of the most frequently stated misconceptions about S-D logic is that it is justified by the fact that many national economies have now become “service economies.” Ironically, the perception of a service economy is mostly an aberration of G-D logic thinking. S-D logic says that the application of competences for the benefit of another party—that is, service—is the foundation of all economic exchange. Thus, even when goods are involved, what is driving economic activity is service—applied knowledge. It is instructive to note that at least 100 years before the term “service economy” was coined and deep in the middle of the “Industrial Revolution,” Bastiat (1848) was arguing that “services are exchanged for services,” essentially, our FP5: “all economies are service economies.”

What has changed today is not that services are overtaking goods in economic activity, but rather that the relative inadequacy of the goods-based classification system of businesses for capturing and informing changes in economic activity is becoming increasingly apparent. Because of the G-D logic-based economic foundation, most countries use an economic classifications system centered on the good (or more generally, units of output—manufactured goods, agricultural commodities; minerals, etc.). One has to look no further than the titles of the classification system(s) in the U.S.—historically, the Standard Industrial Classification (SIC), now supplanted by the North American Industrial Classification System (NAICS).

What is changing today is not the sudden emergence of service but, rather, the combination of (1) increasing ability to separate, transport, and exchange information, apart from embodiment in goods and people and (2) increasing specialization—what Normann (2001) calls “liquification” and “unbundling,” respectively—allowing increased outsourcing. These changes might create new opportunities for service provision but they do not change the nature of what is being exchanged (applied knowledge and skills). They just lead to increases in economic exchanges that are necessarily classified residually, in relation to goods—that is, as “services”—in a goods-centered classification system (Vargo and Lusch 2004b).

The reason this distinction is critical is that the notion of a tertiary and recent “services economy” blinds us to the fundamental nature of exchange and, thus, to opportunities in innovation. We argue that the S-D logic premise that all economies are service economies and the postulate that all businesses are service business liberates marketers to think of innovation in new and innovative ways (as Michel et al. in this issue encourage). That is, innovation is not defined by what firms produce as output but how firms can better serve. It is a distinction we make between competing with services vs. competing through service (Lusch et al. 2007).

S-D logic as a dyadic, firm/customer, exchange perspective

Perhaps partly because we initially focused the S-D logic discussion of value co-creation on “firm”/“customer” exchange, there is a tendency to think that we are suggesting that it only applies to this dyadic exchange. For similar reasons that it is incorrect to suggest S-D logic is limited to marketing management, the firm/customer characterization is also incorrect. That is, while we initially focused on exchange between two parties, we have increasingly tried to make it clear that it needs to be understood that the venue of value creation is the value configurations—economic and social actors within networks interacting and exchanging across and through networks. Consequently, value creation takes place within and between systems at various levels of aggregation. The former point originally centered on descriptions of “value constellations” and “value-creation network partners” and later on discussions of “resource integrators” (Lusch and Vargo 2006a; Vargo 2007). The later point is partially captured in the increasing attention we have given international (e.g., country-to-country) exchange (Lusch et al. 2006) and employee treatment (e.g., Lusch et al. 2007). More recently, we have been extending the applicability of S-D logic to all entities that exchange to improve their own state of being (e.g., individuals, families, firms, societies, nations, etc.).

Increasingly, some of expanded applicability is occurring in conjunction with the development of “service science,” an industry-led, university-assisted movement to create a new discipline to study exchange among “service systems.” As Maglio and Spohrer (this issue) note;

A service system represents any value-co-creation configuration of people, technology, value propositions connecting internal and external service systems, and shared information (e.g., language, laws, and measures). The smallest service system centers on an individual as he or she interacts with others, and the largest service system comprises the global economy. Cities, city departments, businesses, business departments, nations, and national agencies are all service systems.

The general orientation of S-D logic applies to any service system. Even in the somewhat limited-focus of the S-D logic of marketing, it is directly applicable to firms, employees, “suppliers,” customers, and a variety of other stakeholders. That is, the service-for-service perspective of, S-D logic characterizes the interaction within and among all of theses service systems.

Accommodation of social and non-profit marketing and ethics

In a sense, those who contend that we have not dedicated a great deal of attention to societal and ethical issues are probably correct. Yet, S-D logic is particularly accommodating to these issues. As we have noted, we have not intended our explication of S-D logic to be comprehensive; rather, our intention has been to identify S-D logic and invite the discipline to join us in elaborating it. We are gratified that Abela and Murphy take up some of this challenge by examining the ethical foundations of S-D logic in this issue.

Ironically, we suggest that it is the G-D logic on which most of the current work on societal and ethical issues is grounded that is not particularly accommodating; worse, it could be argued that G-D logic is the source of some of the underlying concerns. Consider the difference in the way a logic that says something like “the purpose of commerce is to make and sell more units of output” informs social and ethical issues differently from a logic that says “the purpose of exchange is to mutually serve.” In relation to ethics, Abela and Murphy (this issue) state it much more eloquently.

...there is a compartmentalization of ethical issues in current marketing theory that causes ethical tensions, which in turn give rise to ethical conflict, and that this compartmentalization is largely overcome in the Service-Dominant (S-D) logic proposed by Vargo and Lusch (2004). This compartmentalization is problematic for marketing ethics, both theoretically and practically. The theoretical problem with the current approach to marketing ethics is that the presumption of a clear separation between business theory and ethical theory is difficult to sustain. The practical problem is that ethical theory must be brought in as a check on recommendations generated by marketing theory, creating a separate step that can easily be overlooked by marketing practitioners. The emerging S-D logic with its foundational principles offers a more integrative approach that avoids such compartmentalization, and therefore should reduce ethical conflicts in marketing. We propose that many of the foundational premises of the S-D logic are inherently ethical—they appear to presume or incorporate within them ethical norms.

Similarly, “social marketing” (e.g., Kotler and Zaltman 1971) seems to have several somewhat overlapping meanings, including both the idea of offering only what is good for society and the marketing of ideas and getting people to do things that some party considers good for them. Sometimes it also is attached to non-profit marketing, usually focused on the marketing of intangibles. However, it seems to us that traditional G-D logic is neither accommodating to “goodness” nor the marketing of intangibles. S-D logic, with its core notions that (1) service is the fundamental basis of exchange, (2) service is exchanged for service, and (3) the customer is always a co-creator of value (see FP1, FP5, FP6), is especially compatible with social and non-profit marketing.

More generally, we have suggested elsewhere that S-D logic could provide a foundation for the development of a new theory of society. As we state in Vargo and Lusch 2006, p. 54).

The central notions of S-D logic are that fundamental to human well-being, if not survival, is specialization by individuals in a subset of knowledge and skills (operant resources) and exchanging the application of these resources for the application of knowledge and skills they do not specialize...This shift in focus from operand to operant resources has implications for understanding social interaction and structure that are markedly different from the ones suggested by a focus on the exchange of operand resources and potentially has ramifications for understanding exchange processes, dynamics, structures, and institutions beyond commerce.

Thus, we see S-D logic not only accommodative but potentially foundational to not only social marketing and issues of ethics but also more general societal issues and non-profit marketing.

Modifications and additions

As noted, since about the time “Evolving...” (Vargo and Lusch 2004a) was published, we have noticed wording that could be improved. Additionally, others have pointed out potential wording and conceptual issues. In a few isolated cases (e.g., Lusch and Vargo 2006a; Vargo and Lusch 2006) we have already made modifications to FPs. In the following sections we (1) reemphasize previous modifications, (2) discuss some of the more frequently raised (or noticed by us) issues and modify additional FPs, and (3) provide elaboration in cases in which the issues may be valid but an FP modification might not be warranted, in our opinion. The guiding principle is to make as few changes as possible for consistency while making as many as necessary for clarity. We make one addition to the FPs. Both the original FPs and the modified/added FPs are shown in Table 1.

FP1: The application of specialized skill(s) and knowledge is the fundamental unit of exchange

Ballantyne and Varey (2006) were the first to point out what should have been obvious to us: “unit of exchange” is inherently goods-centric phrase because it suggests that what is being exchanged is units of output, whereas S-D logic revolves around processes. However, we did not consider the correction of this inappropriate word choice to be sufficiently critical to warrant changing it either in the book or subsequent articles, for reasons discussed above. We believe that this special issue provides a more appropriate opportunity and have changed “unit” to “basis.”

Arguably more important, since the “application of skills and knowledge” (operant resources) for the benefit of another party is “service” as we define it (Vargo and Lusch 2004a; 2006), we have simplified FP1 to reflect more directly the central role of service in exchange. That is, “service is the fundamental basis of exchange.”

FP2: Indirect exchange masks the fundamental unit of exchange

For reasons essentially identical to those associated with the word “unit” (of exchange) being an inappropriate choice for FP1, it is not appropriate for FP2. Thus, we also change “unit” to “basis” in FP2: “Indirect exchange masks the fundamental basis of exchange.”

FP4: Knowledge is the fundamental source of competitive advantage

Knowledge and skills represent “operant resources,” as we defined the latter in Vargo and Lusch (2004a). However, when we wrote the original article, the operand/operant resource distinction was generally an unfamiliar one, so we did not use the term in the FPs. The distinction is now not only relatively common knowledge but also seems to have resonated well. Thus, we have more precisely made “operant resources” the focus of FP4: “Operant resources are the fundamental source of competitive advantage.”

Ballantyne and Varey (2006) also argue for a change from “knowledge” to “knowledge renewal” to emphasize their contention that knowledge renewal processes operating at the micro (firm, employee) level are primary to competitive advantage and can be activated by communication and dialog (Ballantyne 2004). We have no argument with their thesis, but see “renewal” as implicit to FP4 and we consider their point an elaboration of, rather than integral to, the premise.

FP5: All economies are services economies

At the time that we initially developed the FPs of S-D logic, we had not fully made the transition form the plural “services” to the singular “service,” to more clearly reflect a process of using one’s resources for the benefit of another entity. Now that we have, it is appropriate to make the change in FP5: “All economies are service economies.”

FP6: The customer is always a co-producer

As discussed, FP6 represents one of several instances in which we got trapped in G-D logic lexicon. We caught this oversight about the time that numerous others were calling it to our attention. Clearly, S-D logic is primarily about value creation, rather than “production,” making units of output. The emphasis was intended to be on the collaborative nature of value creation, but that emphases could easily become lost in the connotations of “production.” Because the distinction between co-creation of value and co-production is critical to the S-D logic thesis, we changed FP6 to refer to co-creation the first time we had a chance (see Vargo and Lusch 2006).

However, we believe that co-production, though distinct from (but nested within) co-creation of value, has a place in S-D logic. Thus, we further emphasized the change to FP6 and the distinction in Lusch and Vargo (2006a). In short, we argue that co-production is a component of co-creation of value and captures “participation in the development of the core offering itself” (p. 284), especially when goods are used in the value-creation process.

Some seem to have interpreted FP6 as a normative statement. It is actually intended as a positive statement. Our argument is that value obtained in conjunction with market exchanges can not be created unilaterally but always involves a unique combination of resources and an idiosyncratic determination of value (also see FP10) and thus the customer is always a co-creator of value. On the other hand, the involvement in “co-production” is optional and can vary from none at all to extensive co-production activities by the customer or user. Hopefully, the co-production versus co-creation of value distinction makes this misinterpretation less likely. FP6 now states “the customer is always a co-creator of value.”

FP7: The enterprise can only make value propositions

It appears that FP7 has been misinterpreted by some or, at least, it is subject to misinterpretation as written. That is, the casual reader could interpret it to mean that once the enterprise has made a value proposition, it is finished with its part of the value-creation process. This was not the intention. Rather, it was intended to convey that the enterprise cannot unilaterally create and/or deliver value. “Value co-creation” (FP6) and “relational” (FP8) imply that both the offeror and the beneficiary of service collaboratively create value. Thus, we have tried to make the intended distinction between value creation and value proposing more explicit in the revised FP: “The enterprise can not deliver value, but only offer value propositions.”

FP8: A service-centered view is customer oriented and relational

As with FP6, it is possible to interpret the original FP8 as normative—that is, advocating a customer orientation and relationship. Rather, it is intended to be a positive statement. That is, in the consideration of value creation with G-D, logic the customer and the firm are separate, with the former as a creator of value and the later a destroyer. With S-D logic, value creation is an interactive process and, thus, the firm and customer must be considered in a relational context. Furthermore, in S-D logic, value is always determined by the beneficiary of service—in the unique experience of that benefit—and, thus it is inherently customer oriented. Ironically, then, no “consumer orientation” is necessary in S-D logic. In fact, we have argued (Vargo and Lusch 2006) that the existence of a “consumer orientation” is evidence of the inadequacy of G-D logic; it is a “fix” for a fundamental flaw. In S-D logic, no such fix is needed.

Similarly, in S-D logic, “relational” is not a normative option. The “co-creation of value” premise (FP5) makes value creation inherently relational. That is, value can not be created any other way. As we noted in Vargo and Lusch (2004a):

It may be argued that at least some firms and customers seek single transactions rather than relationships. If relationship is understood in the limited sense of multiple transactions over an extended period of time, this argument might appear persuasive. However... even apparently relatively discrete transactions come with social, if not legal, contracts (often relatively extended) with implied, if not expressed, warranties. They are promises and assurances that the exchange relationship will yield valuable service provision, often for very extended periods of time. These contracts are at least partially represented by the brand of the offering firm. Part of the compensation for the service provision is the creation and accumulation of brand equity (an off balance sheet resource).

Customers may also not desire multiple discrete transactions. However, the consumer is similarly not freed of relational participation....we argue that value is co-produced (FP6)... Service provision and the co-creation of value imply that exchange is inherently relational.

To emphasize this normative/positive distinction, we have added the word “inherently” to FP8: “A service-centered view is inherently customer oriented and relational.”

FP9: Organizations exist to integrate and transform microspecialized competences into complex services that are demanded in the marketplace

FP9 was not part of the original set of FPs as published in Vargo and Lusch (2004a) but was added in Vargo and Lusch (2006). As we expressed soon after (Lusch and Vargo 2006a, p. 284):

[B]efore the ink was dry on FP9, we realized that the resource-integration role of the firm is equally applicable to individuals and households (Arnould 2006); or more generally, all economic entities are resource integrators. It is this unique application of uniquely integrated resources that motivates and constitutes exchange, both economic and otherwise.

We did not however formally change the FP at that time. We believe that this special issue is the proper place to do so.

But as we do, we find ourselves faced with the recurring difficulty of finding the proper designation for these generic resource integrators. Clearly, “organizations” is not appropriate because individuals are resource integrators. With something less than complete comfort, we have chosen to adopt the term that the IPM Group (and others) uses (e.g., Hakansson and Snehota 1995): “actors.” For present purposes, we have identified the parties involved in exchange relationships as “economic and social actors.” However, we are not forever committed to that term. Alternatively, “service systems” (Spohrer et al. 2007) might be a good, S-D friendly term, but we suspect it is not yet sufficiently familiar to marketing scholars and practitioners. Therefore, the revised FP10 is “All social and economic actors are resource integrators.”

FP10: Value is always uniquely and phenomenologically determined by the beneficiary

As acknowledged, we were probably not sufficiently explicit about the experiential nature of value in “Evolving...” (Vargo and Lusch 2004a). FP10 – “Value is always uniquely and phenomenolgically determined by the beneficiary” – is intended to correct that. Note, however, that we chose the word “phenomenological” rather than “experiential.” This is partly because of the fact that we have found when many people encounter the term “experience,” it often invokes connotations of something like a “Disneyworld event.” Of course, the word experience has several other meanings as well, including previous interaction. However, to the extent that the word experience is intended in a phenomenological sense, we are comfortable with the terms being used interchangeably, as we have done on a number of occasions.

Where to

Ultimately, it is the discipline that will determine where S-D logic goes from here. We have suggested a number of possibilities (Vargo and Lusch 2006; Lusch and Vargo 2006a, c). As with our discussion of misconceptions, we point the reader to those sources. However, we do want reemphasize a few of the possibilities and share some of our vision.

The scholarly work of the large and growing number of scholars who have contributed to the special sessions, independent articles, and special issues and other publications have already contributed to and helped set the course for S-D logic well beyond anything that we have or could have done. The articles that make up this special issue continue to set the course. However, these and other directions remain to be fully explored. Among some of the specific, central issues that are ripe for further elaboration are value propositions, value networks and constellations, dialogue as a dominant communication form, internal service systems, global service systems, and new conceptualization of global wealth and wellbeing based on service thinking. There are of course endless others.

More generally, some have called S-D logic a theory. It is not, at least as we understand the requirement of theory—law-like generalizations, ability to both explain and predict, etc. (e.g., Hunt 2002). We believe that this qualification is not so much a caveat as it is a statement of potential potency. Our characterization of a generalized S-D logic is that it is a mindset, a lens through which to look at social and economic exchange phenomena so they can potentially be seen more clearly. That is, S-D logic functions at the pre-theoretic, paradigm level—though it is also not a paradigm because it does not have “worldview” status.

The more specific, S-D logic of marketing is the result of using this lens to refocus on the particular issues related specifically to marketing. Thus, as we have suggested elsewhere (e.g., Lusch and Vargo 2006c; Vargo and Lusch 2006), it could provide a foundation for a general theory of marketing. Panning back slightly, it could provide a similar foundation for a general theory of the market (Vargo 2007; Venkatesh et al. 2006), which we believe would be an even more solid basis for a general theory of marketing than the economic science foundation found presently.

One particularly intriguing possibility is for S-D logic to provide the philosophical and conceptual foundation for the development of service science, as has been suggested by its primary framers (Maglio and Spohrer in this issue). The intrigue stems from the fact that service science has the potential of taking the perspective of value co-creation and exchange beyond the market by providing a systems orientation that takes the issues out of the economic arena and re-contextualizing them. Thus, ironically, it has the potential of shedding light on the role of exchange between and among service systems at different levels of analysis (e.g., individuals, organizations, social units, nations, etc.), thus enriching marketing in ways that are difficult from its usual tighter, enterprise, economic, and normative focus, even when enhanced through S-D logic. Likewise, panning back still further, S-D logic could provide a basis for reorienting theories of society and economic science.

Some will find these potential directions overly ambitious or at least beyond the scope of marketing-generated scholarship. But consider that, for its first one hundred years, marketing has largely borrowed most of its core concepts, models, and theories and, of course, all of its basic paradigmatic foundation—that is, goods-dominant logic – from other disciplines. Perhaps it is time that marketing, from its somewhat unique, market-centered perspective, contribute more directly to the general understanding of value creation and exchange. This might be at least partially what Alderson (1957, p. 69) had in mind over 50 years ago, when he advocated “What is needed is not an interpretation of the utility created by marketing but a marketing interpretation of the whole process of creating utility.” We believe S-D logic is a step toward realizing Alderson’s call.

References

Abela, A. V., & Murphy, P. E. (2008). Marketing with integrity: Ethics and the service dominant logic for marketing. (in this issue).

Achrol, R., & Kotler, P. (2006). The service-dominant logic for marketing: A critique. In R. F. Lusch, & S. L. Vargo (Eds.), The service-dominant logic of marketing: Dialog, debate, and directions (pp. 320–333). Armonk, NY: ME Sharpe.

Aitken, R., Ballantyne, D., Osborne, P., & Williams, J. (2006). Introduction to the special issue on the service-dominant logic of marketing: Insights from The Otago Forum. Market Theory, 6, 275–281 (Sept).

Alderson, W. (1957). Marketing behavior and executive action: A functionalist approach to marketing theory. Homewood IL: Richard D. Irwin.

Arnould, E. J. (2006). Service-dominant logic and consumer culture theory: Natural allies in an emerging paradigm. Marketing Theory, 6(3), 293–298.

Ballantyne, D. (2004). Dialogue and its role in the development of knowledge. Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing, 19(2), 114–123.

Ballantyne, D., & Varey, R. J. (2006). Introducing a dialogical orientation to the service-dominant logic of marketing. In R. F. Lusch, & S. L. Vargo (Eds.), The service-dominant logic of marketing: Dialog, debate, and directions (pp. 224–235). Armonk, NY: ME Sharpe.

Bastiat, F. (1848/1964). Selected essays on political economy, S. Cain, trans., G. B. de Huszar, ed., Princeton, NJ: D. Van Nordstrand.

Bolton, R. (2004). Invited commentaries on evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. Journal of Marketing, 68, 18–27, (January).

Deighton, J. (1992). The consumption of performance. Journal of Consumer Research, 19(3), 362–373, (December).

Gronroos, C. (2006). What can service logic offer marketing theory? In R. F. Lusch, & S. L. Vargo (Eds.), The Service-dominant logic of marketing: Dialog, debate, and directions (pp. 354–364). Armonk, NY: ME Sharpe.

Gummesson, E. (2006). Many-to-many marketing as grand theory. In Lusch, R. F., & Vargo, S. L. (eds), The service-dominant logic of marketing: Dialog, debate, and directions (pp. 339–353), Armonk, NY: ME Sharpe.

Hakansson, H., & Snehota, I. (1995). Developing relationships in business newtworks. London: Routledge.

Hunt, S. (1992). Marketing is.... Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 20, 301–311, (Fall).

Hunt, S. (2002). Foundations of marketing theory: Toward a general theoryof marketing. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe.

Kohli, A. K. (2006). Dynamic integration: Extending the concept of resource integration. Marketing Theory, 6(3), 290–291.

Kotler, S. J., & Zaltman, G. (1971). Social marketing: An approach to planned social change. Journal of Marketing, 35(3), 3–12.

Levy, S. J. (1959). Symbols for sale. Harvard business Review, 37, 117–124, (July–August).

Lusch, R. F. (2006). The small and long view. Journal of Macromarketing, 26, 240–244, (December).

Lusch, R. F., & Vargo, S. L. (2006a). The service-dominant logic of marketing: Reactions, reflections, and refinements. Marketing Theory, 6(3), 281–288.

Lusch, R. F., & Vargo, S. L. (2006b). The service-dominant logic of marketing: Dialog, debate, and directions, Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe.

Lusch, R. F., & Vargo, S. L. (2006c). Service-dominant logic as a foundation for a general theory. In R. F. Lusch, & S. L. Vargo (Eds.), The service-dominant logic of marketing: Dialog, debate, and directions (pp. 406–420). Armonk, NY: ME Sharpe.

Lusch, R. F., Vargo, S. L., & Malter, A. (2006). Marketing as service-exchange: Taking a leadership role in global marketing management. Organizational Dynamics, 35(3), 264–278.

Lusch, R. F., Vargo, S. L., & O’Brien, M. (2007). Competing through service: Insights from service-dominant logic. Journal of Retailing, 83(1), 5–18.

Michel, S., Stephen, W., & Gallen, A. S. (2008). Exploring and categorizing discontinuous innovations: A service-dominant logic perspective. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, (this issue).

Maglio, P. P., & Spohrer, J. (2008). Fundamentals of service science. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, (this issue).

Normann, R. (2001). Reframing business: When the map changes the landscape. Chichester, New Sussex: Wiley.

Payne, A., Storbacka, K, & Frow, P. (2008). Managing the co-creation of value. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, (this issue).

Penaloza, L., & Venkatesh, A. (2006). Further evolving the new dominant logic of marketing: From services to the construction of markets. Marketing Theory, 6(3), 299–316.

Shemebri, S. (2006). Rationalizing service logic, or understanding services as experience? Marketing Theory, 6(3), 381–392.

Spohrer, J., Maglio, P. P., Bailey, J., & Gruhl, D. (2007). Steps toward a science of service systems. IEEE Computer Society, 40, 71–77, (January).

Vargo, S. L. (2007). On a theory of markets and marketing: From positively normative to normatively positive. Australasian Journal of Marketing, (in press).

Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2004a). Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. Journal of Marketing, 68, 1–17, (January).

Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2004b). The four services marketing myths: Remnants from a manufacturing model. Journal of Service Research, 324–335, (May).

Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2006). Service-dominant logic: What it is, what it is not, what it might be. In R. F. Lusch, & S. L. Vargo (Eds.), The service-dominant logic of marketing: Dialog, debate, and directions (pp. 43–56). Armonk, NY: ME Sharpe.

Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2008). Why service. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science (this issue).

Vargo, S. L., & Morgan, F. W. (2005). An historical reexamination of the nature of exchange: The service-dominant perspective. Journal of Macromarketing, 25(1), 42–53.

Venkatesh, A., Penaloza, L., & Firat, F. (2006). The market as a sign system and the logic of the market. In R. F. Lusch, & S. L. Vargo (Eds.), The service-dominant logic of marketing: Dialog, debate, and directions (pp. 251–265). Armonk, NY: ME Sharpe.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank David Ballantyne and Richard Varey for their insights and suggestions for developing this commentary.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vargo, S.L., Lusch, R.F. Service-dominant logic: continuing the evolution. J. of the Acad. Mark. Sci. 36, 1–10 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-007-0069-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-007-0069-6