Abstract

This contribution looks at how systems modelling can help collaborative law enforcement agencies think about how they might improve their capacity to deal with the rapidly escalating complexity that is associated with transnational and/or organized crime. Some collaborative law enforcement arrangements have existed for many decades, however in recent years more have been established both within and across national jurisdictions. From a complexity-management perspective, such systems make a good deal of sense. However they are very often beset with a wide range of organisational problems which have to be carefully managed. Against this background, the chapter argues that there is a need for theory that can account for the complexity of the challenge and point towards more holistic and integrated solutions. Drawing upon examples representing three distinct levels of collaboration, i.e. the operational taskforce, the national multi-agency system, and the regional cooperation agency, the paper argues that systems-based modelling tools have much to offer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

This chapter examines the role that systems theory and modelling might play in assisting collaborative law enforcement agencies make sense of, and deal with the myriad of organisational challenges that are involved in responding to the various complexities that are associated with modern criminality, particularly that which is organised and which operates across national and/or regional boundaries.

Focussing on relatively new collaborative arrangements that are being introduced within and across national jurisdictions, and globally, the paper argues that there is an urgent need for better discussions about how, organisationally, this problem might best be tackled. In particular, there is a need for theory that can account for the plethora of organisational issues and tensions that are associated with collaborative systems and point towards more holistic and integrated solutions.

In looking at what role systemic thinking and modelling might play in this, the chapter specifically focuses on two key aspects; the first theoretical, the second epistemological. In relation to the former the proposition is that if new organisational systems including meta-systems are being mooted as the best way of responding to the undoubted complexity exhibited by transnational crime, then it logically follows that a complexity-based and systemic perspective is as good a place as any to start looking in the search for possible design solutions. In relation to the latter, although appropriate theory is a good starting point in formulating some general design principles it also seems axiomatic that successful collaboration hinges on finding appropriate mechanisms and processes that will allow key stakeholders to work out themselves the finer details of how this might translate in concrete settings. This strongly suggests the need for an appropriate organising framework to establish some order, to forewarn stakeholders, and assist them in making sense of the plethora of challenges that collaboration presents, and to assist them in coming up with workable solutions.

In what follows the chapter begins by providing some background information on both the nature of the problem as well as how it is being addressed organisationally. It then introduces relevant systems theory and modelling tools and demonstrates how these can be applied across various levels of collaboration including temporary operational task forces, national multi-agency systems, and finally cross-border regional cooperative agencies.

2 Background

Over the last decade or so, government bodies and law enforcement agencies have introduced a raft of new organisational arrangements to address the problem of escalating transnational organised crime. In many regions, what in the past may have been localized and hierarchically organised groups operating in particular areas of criminality, are now being transformed into, or superseded by, sophisticated, flexible network-based structures that can hide their leadership and financial assets in one place while moving quickly across regions and international borders in response to perceived new market opportunities and threats. For example, writing about his experiences with the Camorra crime syndicate in Naples and the surrounding towns, Saviano (2006) highlights key aspects of the changing nature of organized crime. Here the procurement and sale of drugs, people smuggling, counterfeit clothing and electronics is part of a global network of criminal activity that earn billions of dollars. As part of this network the Camorra no longer exhibit signs of a rigid hierarchical organisation, but loosely structured organization that is willing to engage in mutually beneficial deals with anyone in the world. With constantly evolving networks relationships are often transient and transactional. At the same time, established criminals are becoming smarter, many having acquired specialist skills such as cyber crime and money laundering through tertiary study and/or professional training. A similar picture to this is painted by a range of scholars and investigative journalists [see, for example, Saviano 2006; Glenny 2009; Moore 1996; Williams 2006; Wright 2006; Klerks 2003].

The challenges that such developments pose to government agencies and law enforcement agencies are manifold. Globally western government agencies have existed in vertical silos which tend to accentuate accountability, departmental efficiency and structural clarity at the expense of communication and collaboration. In policing, the dominant law enforcement paradigm has been based primarily on the hierarchically-organised local area command or state police force focussing mainly on domestic crime, while intelligence agencies would focus on foreign governments and international security threats. This creates difficulties in areas such as cyber-crime, human trafficking, and narcotics, where criminal activity occurs both inside and outside national boundaries.

With this apparent mismatch between organized criminal networks and traditional policing methods and structures, governments have begun to recognize that law enforcement needs to be more flexible and innovative, and that there must be more collaboration between and across law enforcement agencies and experts from different areas of the public sector. This has prompted governments around the world to establish new organisational structures that broaden policing capability and seek to transcend the normal bureaucratic way of doing business (Homel 2004; Jacobs and Hough 2010).

Typically these new law enforcement agencies work alongside rather than replace the traditional area or state police command; they also operate at numerous levels. At one extreme these can range from temporary ‘operational taskforces’ that might be charged with gathering intelligence on, and/or bringing to justice and prosecuting a particular criminal group, to permanently staffed national cross-jurisdiction agencies that seek to provide an integrated response by combining specialist input from areas such as law enforcement, coastguard, customs, cyber-crime, immigration, taxation, fraud. Beyond that, and at the other extreme, there are longer-established international cooperative agencies such as Europol that convene ‘joint investigation teams’ to coordinate law enforcement activity internationally, and provide analytical, technical and logistical support to national police bodies.

From a managing complexity perspective, creating collaborative systems such as these makes a good deal of sense. However the organisational challenges that they face are manifold. When independent agents or organisational units that have previously operated in a silo fashion are brought together, as they are for example when professional experts participate in an operational taskforce, or when national bodies engage in regional cooperation, it would be naive to assume that there will necessarily be a synergistic relationship. While annual reports, newspapers, websites and increasingly social media proudly highlight the many successes of such collaborations (see, for example, OCTA reports, Europol, OFCANZ, SOCA, ACC) wider testimony suggests that they can be beset with a range of problems including conflicting values, confused identities, difficulties in balancing cooperation and competition, local agendas undermining global agendas, and ambiguous participant ‘rules of engagement’ [see, for example, Kavanagh and Richards 2001; Ling 2002; Lowndes 1988; Ashby 1952]. Wherever the balance between positive and negative outcomes lies, it seems clear that the particular structures and processes that are put in place need to be carefully thought through, and the relationships between the participants and the new ‘systemic whole’ has to be carefully managed.

Amongst the range of potential systemic tools and methodologies that might assist in this project, the discipline of cybernetics, the derivative theory of viable systems and its associated analytical tool, the Viable System Model (VSM hereafter), stands out as being particularly useful. Cybernetics and the theory of viable systems propose solutions to the problem of dealing with complexity so it stands to reason that they are relevant to debates around how to best deal with what is perhaps one of the most complex problems facing society today; the VSM itself specifically addresses the question of how collaborating but otherwise autonomous groups need to be managed in order to generate synergistic outcomes for whatever ‘system’ they participate in. This is clearly relevant when the focus is on collaboration across organisational units. And finally, the VSM framework provides a way of identifying and representing issues diagrammatically in a manner that, in any particular concrete setting, can organise people’s thinking about otherwise complex phenomena, thereby facilitating dialogue on how these structures might best be designed, issues addressed, and the system managed.

3 Theory

Much has been written about the theory and modelling tool used here (Beer 1972, 1979, 1985; Espejo 1989; Espejo and Schwaninger 1993; Espejo et al. 1996), so only a basic outline will be provided. The logical starting point, and one of the foundational concepts in cybernetics is W. Ross Ashby’s so-called ‘Law of Requisite Variety’. Here the term ‘variety’ is basically a proxy for complexity; it refers to the number of possible states exhibited by any ‘environment’ in which the system, including its various processes and the management of these, can be taken to be embedded. Such variety is relative to some defined purpose; it is not an absolute measure. Beyond that, the ‘law’ itself states that the environment can only be ‘controlled’ if the ‘controller’ can match its variety. This idea is captured in the maxim “only variety can absorb variety”.

In the social world, ‘environments’ can exhibit extremely high variety. Hence the ‘controllers’ of systems operating in such a context have to strike a balance by simultaneously increasing the variety of their own system and reducing that of ‘the environment’ (see Figs. 1 and 2). Potentially, the transient, fleet-footed, technologically sophisticated and well-resourced criminal networks described earlier embody extremely high variety, and, as a result, they present major challenges to those who are looking to curtail their activities. In this sense, the enhanced and integrated capabilities of the new organizational and multi-agency arrangements just described, represent what cybernetician would refer to as an ‘amplification’ strategy. At the same time the targeting of particular types of criminal activity, or particular criminal groups, represents an ‘attenuation’ strategy.

What then might this theoretical way of thinking mean ‘organisationally’? To all intents and purposes this is the question that the VSM seeks to address. The answer is presented in the form of a framework that is designed to assist those who are seeking to understand the necessary and sufficient activities that allow a system to survive in uncertain and complex circumstances.

On this account of viability, all such systems (see Fig. 3) include: autonomous ‘operational elements’ that directly interface with the external environment, that enact the identity of the system (‘System 1’); ‘co-ordination’ functions, that ensure that the operational elements work harmoniously (‘System 2’); ‘control’ activities that manage the operational system and allocate resources to it (‘System 3’); ‘audit’ functions that monitor the performance of the operational elements (‘System 3*’); ‘intelligence’ functions, that consider the system as a whole—its strategic opportunities, threats, and future direction; and, finally, an ‘identity’ function, that conceives of the purpose or raison d’être of the system, its ‘soul’, and place in-the-world.

Following the logic of the law of requisite variety, and relative to purposes worked out within the system and ‘managed’ through System ‘5’, the level of autonomy ceded to ‘System 1’ and its various units is commensurate with the level of variety that is perceived to exist in the environment. Thereafter, the main theoretical proposition is that the conditions outlined above: the various systemic elements and the communication channels running between them, and between them and the environment, must be present, working effectively and, importantly, ‘in balance’ through the whole system. If these conditions are not met, then viability is jeopardised.

An important feature of this model is its so-called ‘recursivity’. This refers to the containment of the ‘whole system’ within each of the operational elements. On that basis each System 1 unit can be conceptualised as a viable system in its own right. Equally, any particular system can be conceptualised as an operational component of a higher level system.

The law of requisite variety clearly bears directly on the proposition that policing and law enforcement agencies need, as far as is possible, to match the complexity and variety exhibited by criminal organisations. Of course this is much easier said than done. Considering the mobility and transient nature of many criminal groups, the ‘invisibility’ of their leadership, their inter-weaving of licit and illicit activity, their technological sophistication, and in many cases their massive resource base and covert political influence, it is self-evident that this represents a significant ‘variety’ challenge to cash-strapped, highly bureaucratic, and regionally-focused law enforcement agencies.

Beyond that since there is a ‘pooling’ of law enforcement capabilities and knowledge at multiple levels, the ‘nested’ recursive nature of the VSM offers clear analytical advantages. The basic proposition, to be examined shortly, is that having a clear sense of identity, thinking strategically, planning, controlling and coordinating operations applies at all law enforcement levels irrespective of whether we are speaking of local and temporary taskforces, national agencies or global organisations. Shifting from theory to practice, this framework can be used to examine real collaborate structures to ensure that there are no missing components or ‘missing links in the chain’ that might undermine the ability of the system as a whole to work effectively. Importantly however, viability is not just about the parts of the system, it is also about the relationships between them. The parts need to be working ‘in sync’ and ‘appropriately balanced’. As we shall see shortly some of the debate about the effectiveness of these new law enforcement collaborations can be interpreted as being about missing links, ambiguities or imbalances across the system.

4 Modelling Collaboration Systems

Before we look at specific examples of collaboration from this perspective, let us take a quick look at what has already been said about collaborative arrangements in general. The intent here is to develop some initial appreciation of how this particular model can help people think more systematically about the range of barriers that individually and in combination can frustrate or detract from purposeful collaboration.

Despite the advantages of currently popular concepts such as ‘joined-up government’, the ‘whole-of-government’ or ‘integrated government’ approach, these arrangements are clearly not infallible, and there is now a burgeoning literature covering some of main pitfalls (Kavanagh and Richards 2001; Ling 2002; Lowndes 1988; Ashby 1952). When interpreted within a VSM frame, these difficulties include defining, instigating and disseminating an overall defining sense of identity and core values for the integrated system (S5); ambiguity over accountability (who takes the lead with S3 or is it a shared arrangement?); difficulties in measuring the effectiveness and impact of performance (unclear and/or underdeveloped S3*); opportunity costs of management and staff time spend ensuring integration (resourcing the ‘meta-system’ i.e. S2–S5 and its associated information requirements); budget silos creating difficulties as agencies can fight over ‘who pays’? (how do contributions to S3 work?). In addition, in some areas, cooperation has proven to be difficult due to a lack of trust, or has fallen foul of the personal interests of bureaucrats, politicians and professionals who might be judged more on their individual role or that of their department and not necessarily outcomes-focused (S1 conflict). In some cases collaboration can turn out to be more costly than beneficial due to higher risks of failure as a result of disagreements, complexity and ambiguity over accountability. Given these kinds of difficulties, putting in place adequate S2 mechanisms is critical. Other problems with collaborative arrangements include allegations of empire-building, elitism, inter-agency rivalries, dumping of unqualified personnel, a lack of intelligence sharing between partners (sometimes due to lack of IT integration) and tensions surrounding conflicting objectives.

How then do these kinds of issues play out in the law enforcement context? In this next section some of the commentary is reproduced diagrammatically. This approach makes sense for a number of reasons. Firstly drawings are a good way of presenting complex ideas and data; they are a useful organizing device for helping people reflect on organizational structures and processes, especially when just enough detail is presented to allow people to grasp the key issues (see Checkland 1981; Mintzberg and van der Heyden 1999 for supporting arguments). The VSM, in particular lends itself to this approach. Using the model in this way, and in the organisational context, marks a major shift away from thinking about organisations in hierarchical and boxes/lines organisation chart terms, and towards a more organic approach that shows how an organisation or organisational system interacts with its environment, and how it actually works, instead of how it is supposed to work.

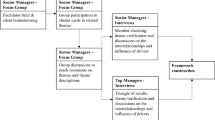

The VSM diagrams reproduced below are in a similar vein. The approach has been to take an example from each of the main multi-agency law enforcement levels that are involved in dealing with transnational crime. Section 4.1 begins with the temporary operational taskforce which is very much at the problem’s ‘coalface’; Sect. 4.2 then considers the permanent national multi-agency law enforcement body; and finally Sect. 4.3 looks at international cooperative arrangements. Since there is a limit as to what level of detail can be included in a single paper, and in particular shown in a diagrammatic model, the paper focuses on some of the more interesting aspects that arise out of this particular theoretical lens. The annotations are only illustrative; just enough information is presented to highlight the potential value and flexibility of the VSM modelling technique, and show how it might be used in this context.

4.1 The Operational Taskforce

The ‘operational taskforce’ concept refers to various forms of temporary collaboration involving specialists from different areas of government and law enforcement. These operate primarily within particular jurisdictions, but can and do operate internationally as well. These taskforces have recently been established in many parts of the world, in particular where permanent inter-agency organisations such as the FBI, the Australian Crime Commission, the UK’s Serious Organised Crime Agency have provided a supporting organisational infrastructure. This is discussed in the next section. The illustration used here is taken from one such organisation, the Organised and Financial Crime Agency of New Zealand (‘OFCANZ’ hereafter) (Fig. 4).

Established in 2008, and housed within the New Zealand Police Force, OFCANZ aims to coordinate the various criminal enforcement units in New Zealand. It works across area command boundaries and partners with New Zealand’s law enforcement, border and regulatory agencies, and financial authorities. OFCANZ also works closely with overseas criminal intelligence and law enforcement agencies.

Despite being housed within, and administered by, the NZ police force, OFCANZ has its own strong S5 identity and branding. Organisationally it operates through permanent, standing and directed taskforces. These taskforces include personnel from OFCANZ, personnel seconded to OFCANZ and personnel from partner agencies including the Inland Revenue Department, the Securities Commission, the National Enforcement Unit, and Customs and Immigration. During its first year of operation OFCANZ taskforces targeted Asian organised crime, ‘outlaw’ motor-cycle gangs, and serious and complex fraud that is associated with organised crime. Since then its’ biggest operational taskforce success to date involved the arrest of members of the internationally-aligned Tribesmen Motorcycle Gang. Members of this gang were subsequently convicted of manufacturing, supplying, and selling and large quantities of methamphetamine.

Looking at the OFCANZ operational taskforces through a VSM lens raises a number of important questions. First and foremost it is hard to quibble with the idea that dedicated multi-capability taskforces (S1a, S1b, S1c etc.) will, in principle at least, provide much greater variety in dealing with complex criminal networks than is the case with the stand-alone area command. S1 taskforces have a broader knowledge base and their capability is enhanced through legislative and technological provisions that allow them to have enhanced surveillance and legal powers. In cybernetic terms this represents significant ‘amplification’ of S1 variety. Equally, taskforces are explicitly required to narrow their focus on a specific criminal activity or group in a manner that cannot be replicated within the area command structure, since the latter has little choice but to respond to serious crime committed ‘on its patch’ whenever this occurs. Theoretically this combination of amplification of capability and attenuation of focus provides a much better chance of obtaining positive outcomes. Having said that, there are some interesting systemic issues that are worth raising and these are discussed next.

One interesting feature of this system is that initially it was intended to merge the NZ Serious Fraud Office with OFCANZ. However the former agency strongly resisted and the merger did not proceed. Anecdotal evidence suggests that working relations between the two organizations has not been seriously compromised, and certainly being ‘part of the system’ (through membership of taskforces) but not ‘part of the organisation’, is not in itself a major impediment to success. However it does raise questions about the appropriateness of the S5 ‘financial crime’ branding of OFCANZ and could lead to concerns over whether the primary responsibility for dealing with crime in this area rests with OFCANZ or the Serious Fraud Office.

Turning now to the operational taskforce ‘meta-system’, Systems 2–5 raise some interesting questions. Since taskforce members are drawn from different organizations and professions, each with their own traditions, cultures and ways of doing things, S2 coordination has been a major organisational challenge. Generally careful management has mitigated potential damage caused through inter-agency rivalries and expressed concerns over information-sharing. However dealing with these kinds of issues, and organisational loyalties more generally, places much responsibility on the shoulders of NZ Police, the host organisation. Pre-existing or latent tensions in these areas are potentially compounded if non-police taskforce members are subject to any excesses in traditional policing approaches to the conduct of operations, its working language and norms of behaviour, ethics and ‘command and control’ leadership styles. Moreover genuine collaboration might be difficult if non-police members come to think that their role is, or might be somehow be seen to be relatively less important. Managing secondments from other areas then arises as a major challenge.

System 3 (‘control’) raises the question of the day to day leadership of taskforces and the allocation of resources to it. In the NZ context the question of ‘who pays?’ is still being worked through. Understandably, on the question of leadership, recent operational taskforces in areas such as gang crime and drugs have been led by the police. However the situation is somewhat less clear cut in areas such as human trafficking, cyber-crime and corporate fraud where the main expertise often resides with other agencies. Here there is a clear dilemma to be grappled with: when there is an insistence on police leadership this can create tensions with non-police members who see themselves as being better informed and better equipped to guide the inquiry. The opposite scenario where someone from a different organization and professional group takes a leadership role within what is essentially a police organization and police culture generates a very different set of challenges.

System 3* (‘audit’) raises a related question. How are the taskforces and taskforce members to be judged? Since the taskforce itself is always set up with a particular set of objectives in mind performance is almost always judged on the ability of the team to obtain tangible results. Anecdotal evidence suggests that this had had a significant impact on the choice of OFCANZ’s early projects, with suggestions that the aforementioned ‘Tribesmen’ operation might have reflected a political imperative to quickly ‘get runs on the board’. In VSM terms since operational taskforces will usually have a very clear sense of identity (S5), i.e. to target a particular area of criminal activity or develop a case for the arrest and prosecution of a particular criminal group, the situation at the higher systemic level is somewhat different. At this level there is clear potential for tension between the longer term focus of OFCANZ’s S5 and the more immediate demands of the taskforce S3*. On the one hand OFCANZ admits that its brief is to minimize the long-term damage and harm caused by organised crime and to make NZ a less attractive destination for international criminal groups. On the other hand, in a country that is under severe pressure to cut costs, and has a relatively short 3 year electoral cycle, there is a view within the organisation that ‘going for the low hanging fruit’ is necessary in order to deliver quick results thereby demonstrating organisational worth to both political masters and the general public.

Judging the performance of individual taskforce members presents another set of challenges. Most members are seconded either from the police or from other organizations, and both therefore are subject to different and sometimes competing performance criteria. The greatest difficulty here is faced by non-police members. Taskforces, by their very nature, are highly focused and are under pressure to ‘get things done’ quickly. This does not always sit well with members from other government agencies who are used to being evaluated on the basis of ‘doing things properly’. One could extrapolate from this the need to select very carefully taskforce members who have the ability to bridge cultural, organisational and professional differences, and, importantly, share a common interest in delivering results in the area of investigation.

Moving on to System 4 raises the question of the need for there being an appropriate balance between the immediate priorities of a taskforce and carrying the learning and experience gained from a particular operation forward to assist in future enquiries. To date the main mechanisms used for this purpose have been a careful recording of and reporting on activities, along with some continuity of membership from one operation to the next.

4.2 The National Multi-agency Law Enforcement System

The example used here is the United Kingdom’s ‘Serious and Organised Crime Agency’ (‘SOCA’) hereafter (Fig. 5).

SOCA, which in 2014 was superceded by the larger ‘National Crime Agency’, is one of a number of national multi-agency law enforcement groups that exist around the world; other examples include the FBI, the Australian Crime Commission, Italy’s ‘Direzione Investigitiva Antimafia’, and the previously discussed OFCANZ.

Prior to 2006, organised crime in the UK was being fought mainly by local area commands and various national intelligence agencies and regional crime squads. At that time there was growing recognition that the traditional local area command was becoming ill-equipped to deal with criminal activity conducted in its region but planned and managed elsewhere; that inadequate intelligence was flowing from higher sources; that it was ill-equipped in terms of surveillance and bugging technology; had limited expertise in fraud, customs and immigration, and ultimately had limited powers in working with criminals. In law of requisite variety terms, this represents a massive variety deficiency relative to that possessed by its criminal adversaries. Other systemic deficiencies included poor communication; inadequate coordination, and even competition across area commands (S2); inadequate resourcing through S3; and a traditionally strong S5 that puts heavy emphasis on maintaining the peace, promoting safety, and dealing with criminals in the local area.

In addition to this, and at the higher systemic level, national law enforcement agencies such as the National Criminal Intelligence Service, the National Crime Squad, and the National Hi-Tech Crime Unit were restricted in their actions due to bureaucratic struggles between them, difficulties in the sharing of information and intelligence and the large amounts of time taken to implement any actions or changes. There was also a perceived duplication of work across these agencies (Harfield 2006; Segell 2007; The Strategy Unit 2009).

In recognition of these sorts of issues, it was decided that there was a need to replace these individual agencies with a single body focusing its combined resources on a single strategy designed to operate more effectively in a less organisationally fragmented manner and to better equip it in dealing with an increasingly borderless criminal world. SOCA was established in 2006 for that purpose.

Organisationally, SOCA is divided into four specific groups each specialising in a separate area. In VSM terms, three of these directly enact the purpose of the organisation and are therefore part of the SOCA S1. These are ‘Intelligence’ which is responsible for gathering and analysing information and building alliances with other agencies; ‘Enforcement’ which provides an operational response to identified threats and builds cases against targets; and ‘Intervention’, which focuses on asset recovery and international work. The other key organisational unit, ‘Corporate Services’ is responsible for resourcing and capability-building (S3). In aggregate, these groups contribute to the S5 Mission of SOCA which is to: “reduce the opportunities for organised criminals to make money, disrupt and dismantle their enterprises, and raise the risks they run by more successful and targeted prosecutions of the major figures”.

In theoretical terms, the consolidation of previously fragmented activities in the new organisation represents a signification increase or amplification of S1 operational variety. This is further enhanced since SOCA’s law enforcement officers are now endowed with increased authority and have the powers of a police constable, a customs officer and an immigration officer. These powers are in addition to new prosecution structures, which include being able to offer criminals reduced sentences in return for cooperating with the investigation and testifying against fellow criminals, and compelling witnesses to answer questions valuable to an investigationFootnote 1.

In dealing with sophisticated criminal groups, the enhancement of S1 operational variety is clearly critical. However, as was said earlier, the balance of activities across this subsystem is equally important. Here criticisms of SOCA have not been in short supply. It seems that many within the organisation, as well as some outside of it, have accused SOCA of focussing too much on the gathering and processing of intelligence, building up a “never-ending criminal intelligence picture” and, in spite of its stated priority, failing to “stem the flow of drugs into the country” through a lack of operational activity (Laville 2009). In response, SOCA’s (Serious Organised Crime Agency 2009) claimed that its’ operation led to drugs shortages in some parts of the UK, and that it would be unreasonable to expect a major turnaround in criminal activity during the first few years of its operation.

SOCA’s S3 has also come under attack, critics accusing it of being a “top-heavy” organisation in terms of management with many complaints having emerged from those within the organisation that it has been wasting money on top management. It is portrayed as an organisation which is “cautious and bureaucratic, overburdened with managers and inexperienced at the sharp end” (Laville 2009). Moreover there are questions about the balance between S3 and S4. An external review of SOCA arose out of claims that there is too much forward thinking, too much strategising and planning (S4), and not enough activity to support current operations (S3). Aside from this systemic imbalance between ‘the future’ and what might be described as ‘the here and now’, others (see, for example, Edwards 2008)Footnote 2 draw attention to the overall lack of resources allocated to SOCA, and point to the relative funding allocated to fighting organised crime and terrorism (in 2008 £457 m and £2500 m respectively), as an indication that the fight against organised crime “remains subordinate to the effort to combat global terrorism” (Williams 2006, 203). The argument seems to be that because terrorism is a “highly-visible threat” it tends to receive a well-resourced response. Meanwhile, organised crime operates in an ‘under the radar’ fashion and therefore acquires less attention. But as Edwards rightly states, “out of sight should not mean out of mind” (Edwards 2008).

Turning now to S3*, evaluating the performance and success of SOCA is a difficult task. SOCA itself claims that this is particularly challenging in key, but often ill-defined performance areas such as the quality of the intelligence it is collecting, and evidence of changes occurring in criminal markets that might indicate that criminals are finding the United Kingdom a more hostile environment in which to operate (Serious Organised Crime Agency 2009). Moreover, the aim of reducing harm is a difficult concept to measure compared to the usual means of measuring crime figures to judge the effectiveness of certain crime fighting initiatives. It must also be noted that many of SOCA’s successes will not have been able to be revealed to the public for reasons of confidentiality.

Questions are also being asked about which body should be given responsibility for SOCA’s S3*. To date the organisation itself has been responsible for its own assessment, and in the operational areas of law enforcement this was always going to present challenges. As Eades (2007, 11) notes, “Public confidence was expected to be difficult to capture (due to the) weak mechanisms of accountability and oversight, far-reaching powers, and politically appointed leadership of this criminal justice organisation”. The British Government is now saying that due to its low public profile and perceived lack of results it is necessary for SOCA to be policed by a body other than itself. It is also concerned that SOCA is not as accountable in day-to-day situations as are other law enforcement agencies, especially the Police.

4.3 The Regional Cooperative Agency

Moving up another organisational and systemic level, our third illustrative agency is Europol, colloquially known as ‘The European Police Force’ (Fig. 6).

Since Europol has been widely discussed elsewhere, (see, for example, Brady 2008; van Duyne 2007; van Duyne and Vander Beken 2009), the level of background detail provided here is kept to a bare minimum.

Although first established through the Maastricht Treaty in 1992, the current Europol regime began in 2005. At that time, 27 Ministers of the European Community agreed on a ‘European Criminal Intelligence Model’ for coordinating investigations using ‘unique information capabilities’ and the expertise of permanent staff as well as police officers seconded from member states. Their role is to identify and track the most dangerous criminal networks in Europe. This ‘intelligence-led’ policing stresses the collaborative targeting of member state police resources on particular criminal groups. To that end, Europol is involved in thousands of cross-border investigations each year. It claims to have disrupted many criminal networks, contributed to the arrest of thousands of dangerous criminals, and the recovery of millions of Euro in criminal proceeds.

In addition to the high variety that is vested in its analytical and technological capabilities, there are two systemic features of the Europol approach that are particularly worth highlighting here. The first is the idea of the ‘Joint Investigation Team’ (‘JIT’); the second, what is arguably Europol’s seminal product for policy–makers and police chiefs, the annual Organised Crime Threat Assessment (‘OCTA’).

JIT’s were first set up in 2000. Prior to their establishment, all cross-border investigations required a ‘Mutual Legal Assistance’ request between Member States which, in many cases, was a slow, bureaucratic and in systems terms ‘low variety’ process. In addition to harnessing Europol’s enhanced analytical and technological capabilities, JIT’s seek to amplify variety by better coordinating international investigations, improving the exchange of information across Member States, speeding up investigations, and allowing Member States to share ‘best practice’ and enhance trust. They also avoid inefficient and costly ‘double’ investigations. From a ‘variety-engineering’ perspective, all of this makes good theoretical sense. Despite this, and on Europol’s own admission, the take-up of JIT’s has not been as great as expected. There are some interesting systemic issues that might explain this.

Looking first at the VSM’s System 5, de Buck (2007) has noted that there has always been some ambiguity within Europol concerning the content and scope of a JIT. Specifically doubts have surrounded whether the whole JIT system within Europol is to support national police organisations, or, engage in operations, or do both. Over time Europol’s role in a JIT has erred towards providing analytical, technical and logistical support and to be facilitation-focused; however its own documentation shows that there is still scope for operational involvement (Europol 2009). This seems to have created tensions between it and Member States. Another interesting systemic feature is that although the JIT’s are very much part of the Europol system, they are not ‘owned’ by it. Indeed Europol itself can only recommend the establishment of a JIT; their actual establishment, operation, and leadership is entirely at the discretion of individual Member States. This is a very interesting systemic feature that potentially has both positive and negative consequences. On the positive side this organisational arrangement ought to nullify the impact of what Beer (1972) refers to as ‘pathological autopoiesis’, i.e. a situation, common in many large organisations, where the S2–S5 ‘meta-system’ becomes bureaucratically self-serving, seeing itself as a viable system in its own right, instead of a set of processes that are designed to support operations. In Europol’s case, this might apply had the experience of JIT’s been particularly successful. On its own admission though, this has not been the case. Currently around 40 JIT’s are in operation; however the take up has been very slow.

In terms of the meta-system (S2–S4) ‘management’ of the JITs, the organisational/professional impediments to collaboration that exist within a single jurisdiction are potentially many times magnified when this is expected to occur internationally. Coordination issues associated with perceived threats to sovereignty, different languages, and cultures, arise as potential pitfalls. Even mundane logistical problems such as members travelling and living away from home can be problematic. The day-to-day S3 resourcing and control of JIT’s has also created difficulties. For example, executive action can only take place on foreign soil when it is conducted according to the law of that particular land. This creates difficulties in defining the applicable law for a JIT that is working across Member States and for individual members who may be required to carry out investigative measures in accordance with unfamiliar law. S3 also raises questions about the leadership of JIT’s. Under the current arrangements, leadership is ceded, not to Europol, but to a member from one of the participating Member States. Again this is not an insurmountable difficulty, however it does suggest that Europol needs to carefully manage the process since nationalistic tensions, cultural and language difficulties, and traditional rivalries almost inevitably will arise. In particular much responsibility rests on the shoulders of the JIT leader who must manage the possible tension that is created in the trade off between sharing and protecting country-specific knowledge while maintaining a careful balance between competition and cooperation (Parkhe 1993). In policing this becomes a very difficult issue since much of the most useful intelligence on criminal groups comes from ‘unofficial’ sources such as informants and undercover agents. Sharing such information even with trusted and close colleagues carries significant risk.

Another issue concerns the use and disposal of information obtained through a JIT. Currently national laws and law enforcement conventions impose limitations on the use of information obtained by Europol officials while taking part in a JIT; in particular the inclusion of information obtained into Europol databases is subject to the approval of the participating Member States. From a systemic perspective (S4) this might make it difficult to carry forward learning from one JIT to another.

Given these systemic difficulties, it is perhaps unsurprising that where JIT’s have worked particularly well, this has typically involved a small number of Member States (usually 2) which have been able to build and capitalise upon pre-existing mechanisms for coordination, communication and control, and have not had to develop these from scratch. Block (2008, 80), for example, cites the case of a successful joint UK/Netherlands drug trafficking JIT which was initiated through a ‘bottom-up’ initiative of well-connected police commanders in the two countries and where considerable effort was required in putting in place housing, finance, and training and regulations for the seconded British officers. At the end of this assignment, and in the words of one of the involved police commanders: ‘we proved that a JIT can work however I can’t say that a JIT provides a bigger chance of getting results than a parallel investigation (in the two countries)’ (Block 2008, 80). Elsewhere JIT’s have worked well in cases of geographically and/or culturally closely aligned countries. For example, recent successes have included French-Spanish JIT’s targeting Basque terrorism, Belgium-Netherlands JIT’s targeting drugs and UK-Netherlands JIT’s targeting drugs and human trafficking.

Similar systemic issues to those just discussed arise in relation to the ‘Organised Crime Threat Assessment’ (‘OCTA’ hereafter), which we have already said is Europol’s core product of the intelligence-led policing concept for policy makers and police chiefs. OCTA was introduced in 2004 in order to provide for a more future-focused and pro-active assessment of organised crime. The key OCTA instrument is three detailed questionnaires that are completed by Member States on an annual basis. One questionnaire focuses on criminal groups, the second on general criminal activities, the third on a specific criminal activity such as money laundering or, in 2014, cyber-crime.

Since OCTA is undoubtedly the key formal mechanism within the Europol system that facilitates plugging the gap between projected futures (S4) and day-to-day operations (S1), it plays a pivotal role. However, as with the JIT’s, experience to date has been mixed, with varying levels of support being provided by Member States. By most accounts, some Member States have taken the project seriously while others have paid lip service to it, preferring instead to fight transnational criminal activity independently or through limited bilateral and often informal cooperative arrangement with close neighbours. Other criticisms have centred on the methodological limitations of the OCTA instrument. Thus, in a scathing attack, van Duyne (2007) raises questions about the reliability of the data, its processing, the reliability of the findings, and validity of the conclusions about the stated threats. Van Duyne further claims that the questionnaire is unwieldy, impractical, user-unfriendly, and frequently ambiguous in its wording. To cap it off, he submits that most of the threat observations could just as well have been made 15 years ago. It is difficult to assess these claims; however, it is worth noting that Europol has recently taken steps to improve the instrument.

By necessity, methodological limitations and varying levels of OCTA support from Member States impacts on the quality of feedback provided back to national police organisations. Hence, any lapses or omissions has the potential to seriously undermine the viability of the whole system. That being the case, even if Europol as a whole could be shown to be viable in all other respects, any S4 deficiency needs to be taken seriously. Typically problems occurring at this level show up at some point in the future when unforeshadowed changes in external circumstances leave the organisation ill-equipped to cope. In the fast-changing world of trans-national crime this remains a distinct possibility.

5 Conclusion

At any point in time, it is self-evident that the level of transnational organised crime is the result of a complex combination of social, cultural, political and economic circumstances, the complete eradication of which is beyond the capacity of even the most generously resourced collaborative law enforcement agencies. Notwithstanding this, the level of public expectation and financial resources that are vested in them dictates that the agencies that have been charged with this responsibility operate as efficiently and effectively as possible.

To this end, the paper has argued that the debate about the functioning of these systems can benefit through being more theoretically informed than seems to have been the case hitherto. Overwhelmingly, discussions about operational taskforces, multi-capability national and regional agencies have either been exclusively descriptive, or they have tended to focus on some organisational aspect without placing it in the wider context. It is all very well, for example, pointing the finger at the lack of trust across collaborating partners or inadequate resourcing, on the assumption that addressing these issues will deal with the problem. Systemic thinking suggests the need for more integrated and holistic strategies. The point is well captured in Schwaninger’s (2001, 138) claim that ‘the result of a management process cannot be better than the model on which it is based, except by accident’. If then, there is any truth to the claim that the architects and managers of these new collaborative structures are fragmented in their thinking about the problem, then the ‘solutions’ are likely to be equally fragmented.

Against that background, the argument is that there is an urgent need for better theory to be injected into discussions about how, organisationally, this problem should be managed. In particular there is a need for theory that can account for the complexity of the challenge and point towards more holistic and integrated solutions. The law of requisite variety and the theory of viable systems are particularly well-suited to this task. More generally, systems thinking and problem structuring methods and tools have much to offer in dealing with the complexity faced by crime-fighting law enforcement agencies. System Dynamics and causal loop modelling, (for example Senge 1990; Vennix 1996), is potentially useful in examining non-linear and time-lag effects in criminal policy analysis and design; the conceptual modelling tools used in Soft Systems Methodology (Checkland 1981; Checkland and Scholes 1990) can assist in modelling the complex inter-related activities that occur on both the supply and demand sides of crime, this being a necessary precursor for the kind of interference, intelligence-gathering and prevention strategies that the aforementioned collaborative agencies are involved in; cognitive mapping or strategy ‘journey-making’ (Eden and Ackermann 1998) is useful for developing more holistic crime-fighting or prevention strategies that can foreshadow the unintended consequences of what ostensibly are sensible crime fighting or prevention strategies.

In terms of the specifics of inter-agency collaborative law enforcement the paper has identified a range of real or potential ‘systemic deficiencies’, all of which translate into questions that the various stakeholders need to think very carefully about.

Mapped out in the text and in diagrammatic form, some of the more important questions about these collaborative arrangements include the following. Most obviously there is the question of whether people will want to work together. We cannot assume this to be the case, no matter how compelling is the argument for collaboration. Will long-standing historic, cultural and operational tensions stifle cooperation? Will politics compromise results? Will governments dedicate sufficient, long term funding if results are not instant? While the positive implications for such collaborative projects are enormous the enthusiasm around it may be constrained by these cultural, political and resource issues. Moreover successful implementation would appear to depend on a number of things including developing clarity over identity and purposes, knowing who and/or what is responsible for coordination, knowing how leadership should work, knowing what each individual and group’s role is, who they report to, how performance is assessed, how resources are managed, and, perhaps above all else, how these various groups ‘fit together’ both horizontally and vertically as part of a synergistic and coherent whole.

References

Ashby WR (1952) Design for a brain. Chapman and Hall, London

Beer S (1972) Brain of the firm. Allen Lane, London

Beer S (1979) Heart of enterprise. Wiley, Chichester

Beer S (1985) Diagnosing the system for organization. Wiley, New York

Block L (2008) Combating organized crime in europe: practicalities of police cooperation. Policing 2(1):74–81

Brady H (2008) Europol and the European criminal intelligence model: a non-state response to organized crime. Policing 2(1):103–109

Checkland P (1981) Systems thinking, systems practice. Wiley, Chichester

Checkland Peter, Scholes Jim (1990) Soft systems methodology in action. Wiley, Chichester

de Buck B (2007) Joint investigation teams. ERA Forum 8:253–264

Eades C (2007) Serious organised crime: a new approach. Kings College, Centre for Crime and Criminal Justice Studies, London, pp 1–11

Eden C, Ackermann F (1998) Making strategy: the journey of strategic management. Sage, London

Edwards ALM (2008) Criminology and criminal justice. 8:363–388

Espejo R, Harnden R (eds) (1989) The VSM: interpretations and applications of S Beer’s VSM. Wiley, Winchester

Espejo R, Schwaninger M (1993) Organizational fitness: corporate effectiveness through management cybernetics. Frankfurt, Campus

Espejo R, Schuhmann W et al (1996) Organisational transformation and learning: a cybernetic approach to management. Wiley, Chichester

Europol (2009). EU organised crime threat assessment, European Police Office (Europol), pp 1–64 (39)

Glenny M (2009) McMafia: seriously organised crime. Vintage Books, London

Harfield C (2006) SOCA-a paradigm shift in british policing. Br J Criminol 46:743–761

Homel P (2004) Trends and issues in crime and criminal justice: the whole of government approach to crime prevention. Australian Institute of Criminology, Australian Government, Australia, pp 1–6

Jacobs P, Hough M (2010) Intelligence cooperation to combat terrorism and serious organised crime: the United Kingdom model. Acta Criminologica 23:94–108

Kavanagh D, Richards D (2001) Departmentalism and joined-up government: back to the future? Parliamentary Aff 54:1–18

Klerks P (2003) The network paradigm applied to criminal organisations: theoretical nitpicking or a relevant doctrine for investigators? recent developments in the Netherlands. In: Edwards AG (ed) Transnational organised crime: perspectives on global security. Routledge, London

Laville S (2009) Government’s organsied crime strategy has echoes of the past. http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk/2009/jul/13/organised-crime-government-analysis

Ling T (2002) Delivering joined-up government in the UK: dimensions, issues and problems. Public Adm 80(4):615–642

Lowndes VSC (1988) The dynamics of multi-organisational partnerships: an analysis of changing modes of governance. Publ Adm 76:313–333

Mintzberg H, van der Heyden L (1999) Organigraphs: drawing how organizations really work. Harvard Bus Rev 77(5): 87–95

Moore RH (1996) Twenty first century law to meet the challenge of twenty first century organised crime. Technol Forecast Soc Change 52(2):185–197

Parkhe A (1993) Strategic alliance structuring: a game theoretic and transaction cost examination of inter-firm cooperation. Acad Manag J 36:794–829

Saviano R (2006) Gomorrah. Picador, New York

Schwaninger M (2001) Intelligent organizations: an integrative framework. Syst Res Behav Sci 18:137–158

Segell GM (2007) Reform and transformation: the UK’s serious organized crime agency. Int J Intell Counter Intell 20(2):217–239

Senge PM (1990) The fifth discipline. Doubleday/Currency, New York

Serious Organised Crime Agency (2009) Annual plan and report. T. H. Office, The Stationery Office, London

The Strategy Unit (2009) Extending our reach: A comprehensive approach to tackling serious organised crime. The Home Office, The Stationary Office, UK, pp 1–81

van Duyne PC (2007) OCTA 2006: the unfulfilled promise. Trends Organ Crim 10:120–128

van Duyne PC, Vander Beken T (2009) The incantations of the EU organised crime policy making. Crime Law Soc Change 51:261–281

Vennix JAM (1996) Group model building: facilitating team learning using system dynamics. Wiley, Chichester

Williams P (2006) Transnational criminal networks. In: Arquilla J, Ronfeldt D (eds) Networks and netwars. Santa Monica, Rand, pp 61–97

Wright A (2006) Organised crime. Willan Publishing, UK

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Brocklesby, J. (2016). Using Systems Modelling to Examine Law Enforcement Collaboration in the Response to Serious Crime. In: Masys, A. (eds) Applications of Systems Thinking and Soft Operations Research in Managing Complexity. Advanced Sciences and Technologies for Security Applications. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-21106-0_2

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-21106-0_2

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-21105-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-21106-0

eBook Packages: Physics and AstronomyPhysics and Astronomy (R0)